Fun with faux fur

Learn about the challenging, meticulous treatments behind the restoration of two fur parkas.

August 4, 2020

When treating objects, one of the fun challenges conservators regularly encounter is the imitation of an existing material or piece of an object if something is missing or to bridge a hole or gap. This calls for a lot of creativity and imagination, as we are often trying to mimic a detail or element using different materials from the original. For example, we recreate missing buttons, sculptural elements such as fingers or toes, and handles on objects, as well as fill holes in woven basketry, leather upholstery, glass and ceramics, and wooden objects. Like a magician’s sleight of hand, if successful, our work is imperceptible, except at close range.

Two recent treatments required different approaches to imitating caribou fur. The objects—fur parkas for young girls—are both sewn from caribou, though each is quite distinct from the other. Both required fills for holes in their fur.

These are objects of great beauty, and an important aspect of their design is the use of a selection of fur taken from specific parts of the animal’s body, with the makers employing a variety of methods to symbolically represent the liaison between animals and humans. The hoods of both parkas incorporate the head, nose, and ears of the caribou. When the wearer puts on the parka, she takes on the form of the animal, signifying a bond with the caribou. ME966X.124.1 has been fitted with an amaut, a small pouch at the back, which references the pouch found on the back of a woman’s parka used to transport her young child. Two amulets suspended from the centre back of the garment represent the properties of speed and endurance and imbue the wearer with quickness and dexterity (Hall, 120).

The sleeves on the second parka, ME983X.71.1, have strips of white fur inset around the forearms, suggesting the strength required to prepare and sew the skins; this refers to the woman’s role in the transformation process from skin to garment (Issenman, 181-182).

A shoulder on one of the parkas had a large tear along the top, which had become misshapen and quite stiff over time, making it impossible to align the two sides properly.

After reshaping the shoulder area with localized humidification and repairing the tear, it became evident that a section of fur was missing.

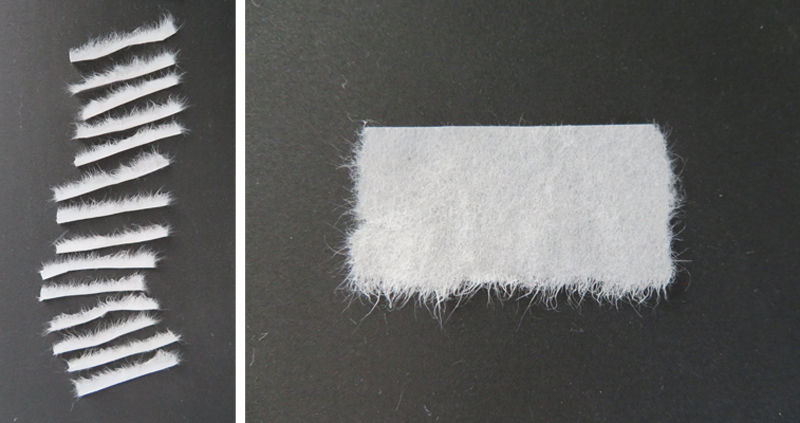

The fur in this spot has a thick texture, with short, somewhat wavy fibres. To create an effective imitation of the three-dimensional texture and appearance of fur, I used a type of handmade Japanese tissue paper. This particular paper is made from long plant fibres, which lend the paper a certain amount of strength.

The process of creating a three-dimensional imitation of fur begins with a piece of tissue that is divided into uniform strips. The paper is first marked with lines of water applied with a paintbrush, and then torn along these lines. This preparation results in strips with feathered edges, lending them a fuzzy silhouette.

Each prepared strip is folded in half, lengthwise, and adhered to a paper support coated with a layer of adhesive, with only the fold line touching the support.

As it is gradually built up in lines of folded strips, the paper visually and texturally resembles a piece of fur.

The paper fur is tinted to blend in with the surrounding fur, then adhered in place to finish the repair.

With the other parka, the two holes were located in very different types of fur.

The fur on the shoulder is dark brown and quite thick and fine, whereas the fur on the chest, while also relatively thick, is much coarser than that on the shoulder, and much lighter in colour.

The texture of these two pieces of fur is straighter than that found on the shoulder of the first parka. For these fills, I used merino wool fibres and undyed fine silk threads. The silk threads are slightly thicker than the merino fibres, and resemble the straighter, coarser fur on the chest of the second parka.

I dyed the merino fibres in several shades of brown, combining different shades to mimic the variations found in natural fur. With a felting needle, I attached the mixture of merino fibres to a piece of non-woven polyester fabric. For the other patch, I started with two-ply natural-coloured silk threads, which I unravelled into individual strands. To these, I added merino wool fibres, again to mimic the natural variation in the fur. The same felting technique was used to secure the silk and wool fibres to the synthetic fabric.

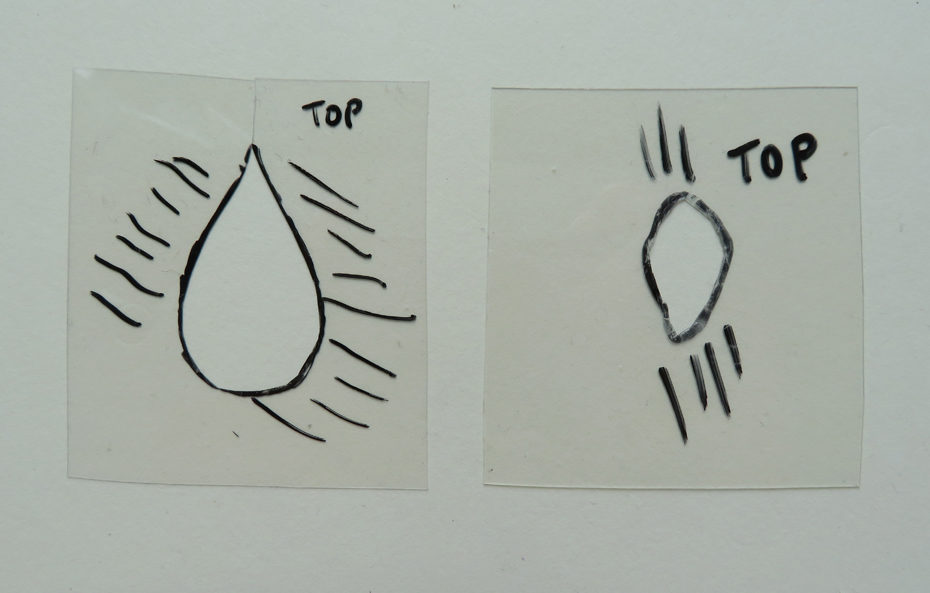

To shape the fills, I created a template of each hole, using a piece of Mylar—a clear plastic film—on which I traced the outline of the hole and indicated the direction of fur flow with a permanent marker.

The holes were backed with pieces of Japanese tissue, secured in place with a heat-reactivated adhesive. The fills were then adhered to the exposed area of the backing, using a heated spatula.

While the fills serve an aesthetic purpose by allowing for a clearer reading of the object, they are also functional. In the case of the tear across the top of the shoulder, filling the loss further stabilized the realigned opening. Backing the holes in the second parka and completing these repairs with the faux-fur fills reinforced these two spots in the garment. Such stabilization is an important consideration as both parkas were to be displayed on mannequins in an exhibition. The process of mounting a garment on a mannequin involves some manipulation of the object and, no matter how delicately this is undertaken, there is a risk of tearing in fragile areas. Both treatments reinforced the integrity of the parkas and allowed for their exhibition.

REFERENCES

- Hall, Judy et al. (2001). « Following the traditions of our ancestors », dans Fascinating Challenges : Studying Material Culture with Dorothy Burnham, Hull, Musée canadien des civilisations, p. 120.

- Issenman, Betty Kobayashi (1997). Sinews of Survival: The Living Legacy of Inuit Clothing, Vancouver, UBC Press, p. 181-182.