Capturing History – Daniel Kieffer

A discussion with Daniel Kieffer about the magic of street photography.

August 17, 2020

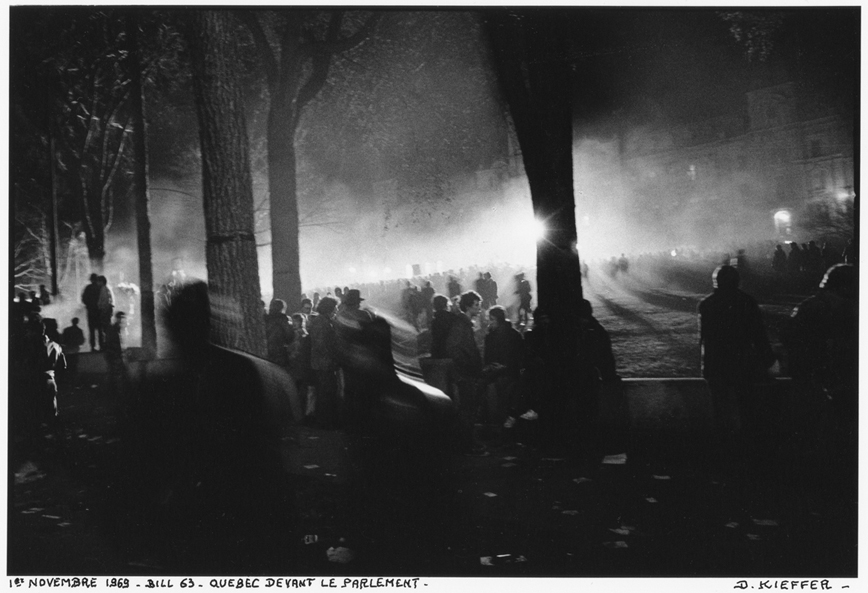

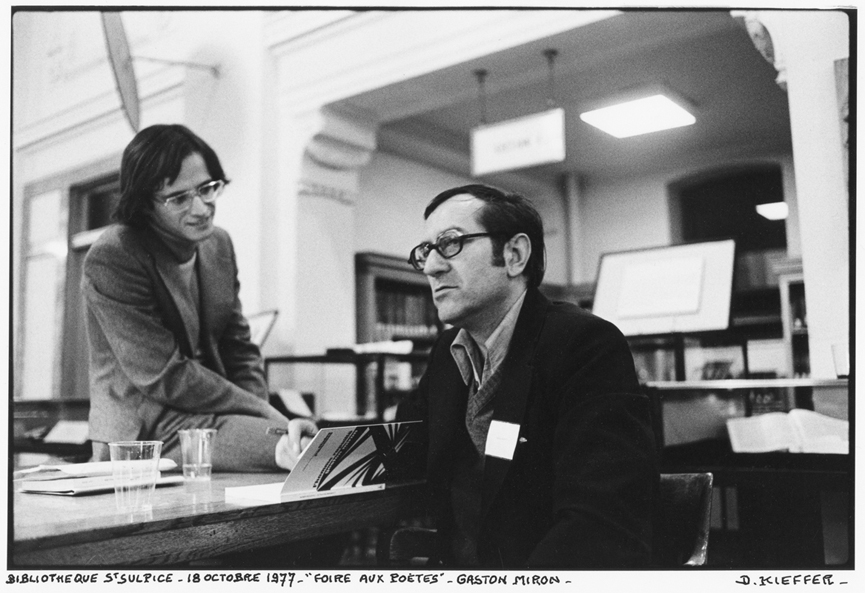

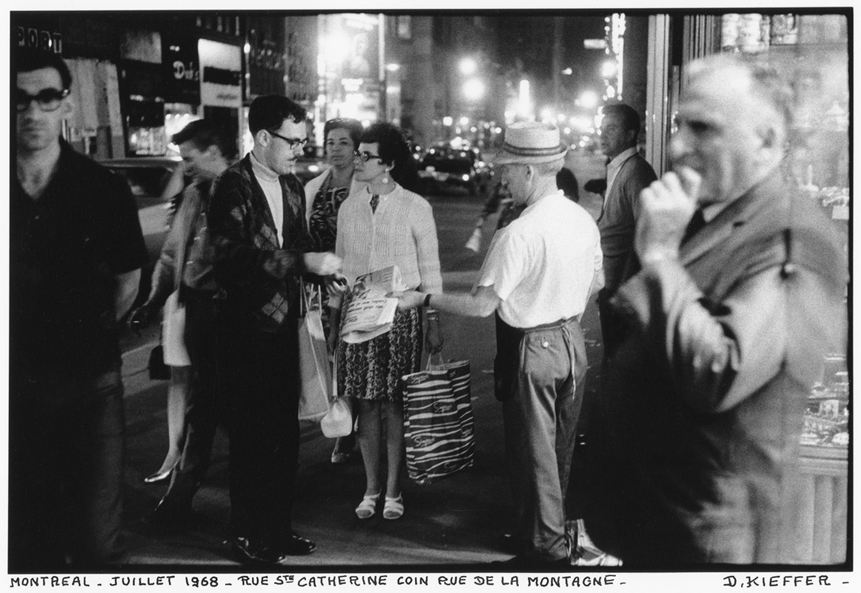

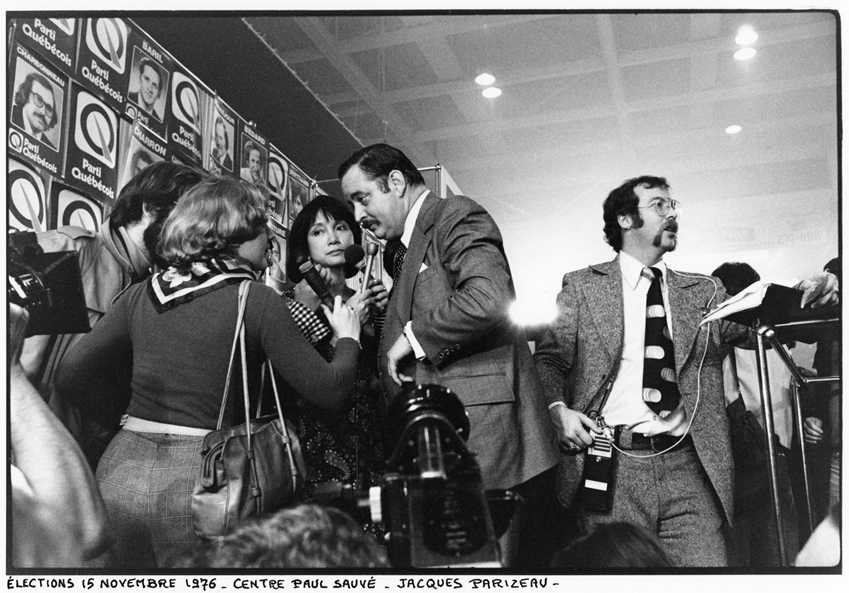

Wearing gloves, I open six black boxes, laying them out on a large table. One by one, I pick up the 363 Daniel Kieffer photographs that were recently added to the McCord Museum’s Photography collection. I suddenly feel very emotional as I peruse large annotated photographs of people I don’t even know. I am surprisingly touched. Moving from one box to the next, I see myriad movements, expressions, smiles and crowds. Though I am simply looking at shades of grey on glossy paper, the effect is strangely compelling. In my hands are traces of vanished moments, somewhere between the unknown and newsworthy, all captured by Kieffer.

Photographer Daniel Kieffer was born in Paris in 1940. After several years of teaching high school while experimenting with photography in his spare time, he decided to emigrate to Quebec in 1966. I always wanted to take pictures. When I arrived here, I told myself to just do it.

We are sitting on his balcony, under the stairs leading to the apartment above. Between us lie two metres and a small metal table. He talks to me about his practice, his career, and his life. From industrial photography at a Beauharnois furniture factory to teaching at Université du Québec à Montréal, his amazing life has been marked by happy coincidences, incredible meetings and impassioned work.

Kieffer free-lanced for the magazine Perspectives, exhibited his work at the Saint-Sulpice library on several occasions, taught briefly in a college, photographed approximately 500 Quebec plays at the Centre du Théâtre d’Aujourd’hui and was then offered a position as lecturer at Université du Québec à Montréal. Between my theatre jobs, UQAM classes and set photography contracts during the summer, I made enough to live on. He became a full professor and completed a master’s degree in communications, specialized in production. I retired from teaching because I did not want to go digital. He suddenly glances over my shoulder at his cat, jumping in the garden.

My favourite type of photography is street photography. The theatre is almost like street photography.

This way of taking pictures takes time. One must spend countless hours walking around, observing people, always at the ready, like an urban anthropologist. As Doisneau said, “Some photos are taken with your feet.” My legs hurt too much now; I can’t do it any more. I take photos of my cat in the garden.

In Kieffer’s work, one can always sense the photographer near his subject and the action. People say that street photography should be shot with a 35mm lens, but I generally used a 28mm. It matches my vision. It’s like being there. Some elements are out of focus, several subjects are back-lit, and hands and bodies can be seen on the periphery. He manages to evoke the great in small moments and small details in great moments. It is dizzying to see these people and shadows start to move; it is like suddenly breathing in a flurry of smells and sounds: cigarette smoke, crowd noises, clicking camera shutters, laughter and shouting. And yet, there is simply a flat photo before us, in black and white. The colours are in us.

Today, everyone has a camera in their pocket and the act of taking a photo has changed completely. There is now a flood of captured moments. While it is a wonderful tool, it is no longer photography. It’s note-taking.Taking notes with images. Documenting what we see to replace our memories or capture an instant so it can be shared.People no longer take time to reflect. Everything has to be immediate, automatic. However, a good photograph must be thought out.

Another thing I like about photography is the material aspect. The photo as object. I am profoundly moved when I see a good print on high quality paper.

Not to mention the magic of the darkroom. Printing a photograph is a laborious process, but it never fails to generate the same reaction in someone seeing it for the first time. I remember, before the digital age, when I would take students into the lab for the first time—it was enchanting to see.

After having gone through these hundreds of photographs, I understand perfectly what Kieffer means when he describes his feelings for the “photo as object.” The physical presence of an original print is incomparable, far removed from an image on a screen.

The McCord’s collection of photographs is a monument. Not to mention all the work the Museum does to promote social photography from the 20th and 21st centuries. By entrusting the McCord Museum with his personal collection, he knows that his work will not languish in a storage box, but will be discovered by Montrealers in future projects.