1949: Dominion Corset Sparks a Scandal

A mid-20th century morality campaign targeted the Dominion Corset Company, protesting that its ads were overly suggestive.

February 14, 2019

A MORALITY CAMPAIGN

The period following the Second World War (1939-1945) was marked by tensions between a desire for moral liberation and a longing to get back to normal domestic life after the upheavals and excesses of the conflict.

Montreal, an “open city” famous for its dynamic nightlife but also for its many gaming houses and brothels, became the focus of morality campaigns aimed both at public licentiousness and at the presumed corruption of police and politicians, accused of complicity with organized crime.

These movements represented the climax of a broader, province-wide moral crusade, piloted by the Church but frequently implemented by lay people, that addressed a variety of issues, including alcohol, clothing and adolescent pastimes.

There had been growing concern since the war about the proliferation of erotic publications, especially “pin-ups,” the slightly risqué pictures of attractive women displaying their voluptuous curves that had been tolerated in wartime for the courage they were said to inspire in soldiers risking their lives for the nation. The sense of outrage intensified in the late 1940s, when advertisers began employing a similar visual language to promote the sale of certain products.

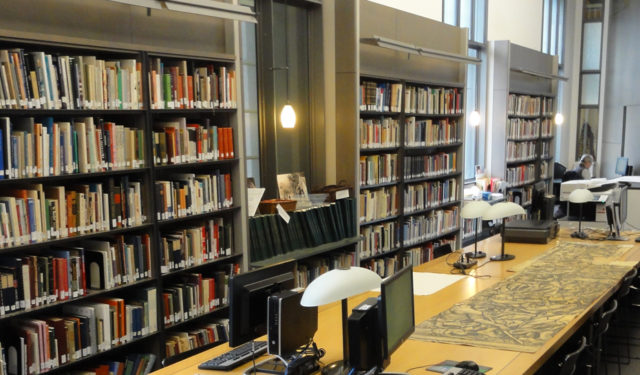

In 1949 the Dominion Corset Company, a Quebec City manufacturer of women’s undergarments, found itself in the eye of the storm. An archival collection kept at the McCord Museum reveals how advertisements this major firm had placed in Montreal and Quebec City buses and streetcars were considered overly suggestive, causing it to become the object of a protest campaign. A fascinating collection of some eighty letters records the disapproval of citizens and clergy alike, but also the company’s reaction to the anger it had triggered.

GROWING PROTEST

Shortly before Christmas 1948, the director of the Canadian Street Car Advertising Co., Ltd. wrote to Monsignor Albert Valois complaining that copies of an advertisement displayed in public transport vehicles were being vandalized by the addition of stickers, probably as a form of censorship. In response, Monsignor Valois, director of the Diocesan Committee for Catholic Action, Montreal overseer of the moral crusade, wrote that although he felt the company “generally ensured its advertisements contain only truly moral prints,” the one in question posed a real problem. “Even though the model illustrated is fully clothed, the drawing is suggestive, and the Ronalds Advertising Agency of Montreal cannot say that I have approved it.”

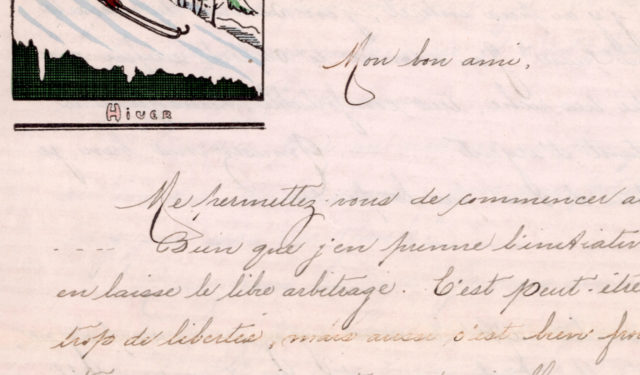

There were no further developments until February 1949. Then, on the 14th of that month, a citizen of Quebec City wrote to Dominion Corset to complain about a “Cordtex bandeau advertisement with a girl in a yellow top, displayed on buses belonging to Quebec Power.” The advertising manager who replied seems not to have taken the writer’s indignation very seriously, and reiterated the idea that the ad had been approved by Monsignor Valois. On hearing this, the clergyman wrote angrily to the company, and soon protest letters were flying left and right, some from Quebec City but the majority from Montreal and the surrounding region.

The protestors, often women, insisted on their power as consumers and their determination to have their views respected. On February 28, the Fédération des dames de Sainte-Anne, in the diocese of Montreal, offered Dominion Corset a reminder:

“We are writing to you in the name of 33,000 ladies. They will all be informed of our petitions to your Company.”

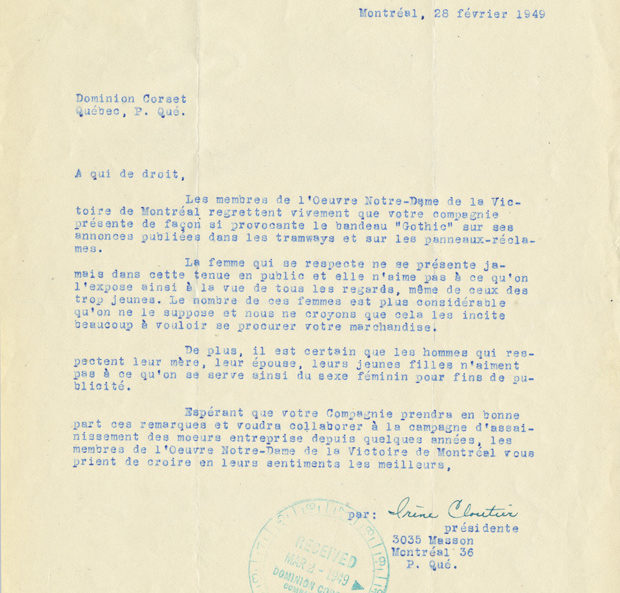

On the same day, the members of Montreal’s Œuvre Notre-Dame de la Victoire pointed out that it was not only a matter of decency, but also of respect for women:

“A woman of self-respect never appears publicly dressed in this manner and does not appreciate being thus exhibited to the view of all, even of those who are too young.”

THE COMPANY YIELDS TO PRESSURE

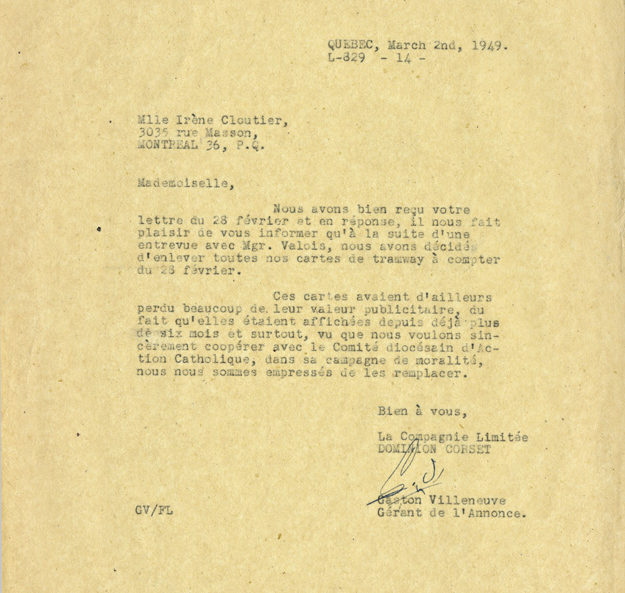

The growing number of letters soon began to worry Dominion Corset. The company contacted Monsignor Valois, eager to assure the auxiliary bishop of their full collaboration. On March 9 the personnel manager sent a detailed memo on the subject of the morality campaign to general manager Pierre Amyot. It notes that the campaign against Dominion Corset had apparently been launched by the Ligue catholique féminine and was part of a broader North American movement.

Certain passages of the memo are quite amusing. For example, discussions with the church authorities seem to have resulted in “acceptance of the idea of portraying busts in blue, green or any other colour that inhibits fleshly thoughts”!

Eventually, given the scale of the protest, the company decided to back down and withdraw the offending ads.

FOLLOWING THE THREATS, CONGRATULATIONS

Once the company’s decision had been announced, a number of protestors contacted Dominion Corset again to express their thanks and applaud them for having done the right thing. On March 18 the chairwoman of the Œuvre Notre-Dame de la Victoire wrote: “Our members deeply appreciate your act of collaboration in the morality campaign being conducted in Quebec City and Montreal.” She went on:

“Please rest assured, dear Sir, that I shall take every opportunity to call attention to the Company’s laudable attitude, which I trust will be well rewarded by an increase in its clientele.”

On March 25 the board of the Assistance maternelle de Montréal stated that “a company that has the courage to act thus deserves that we not forget,” while the members of the Jeunesse indépendante catholique féminine de Montréal informed Dominion Corset that it could count on “the encouragement of all our friends.”

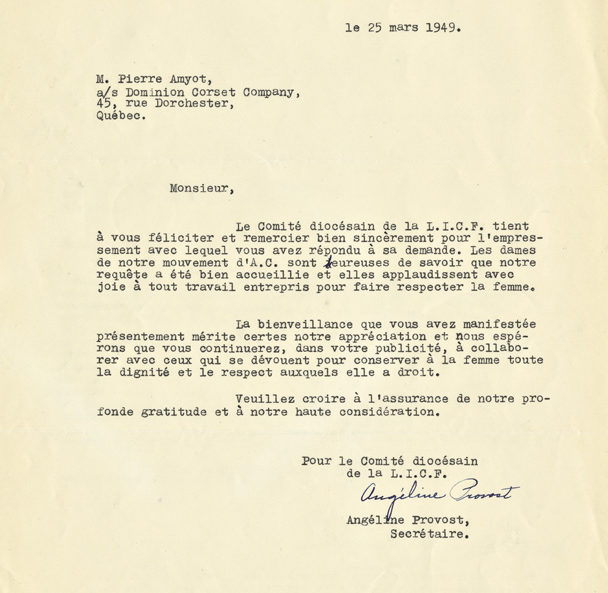

The tone of a number of the letters indicates that the protestors saw the retraction as a victory. The Montreal committee of the Ligue indépendante catholique feminine wrote that its members were “happy to learn that our request has been well received, and warmly commend all efforts to ensure that women are respected.” The league’s letter continues: “We hope that you will continue in your publicity to collaborate with those who seek to protect the dignity and respect that are the right of all women.”

THE EFFECT ON ADVERTISING

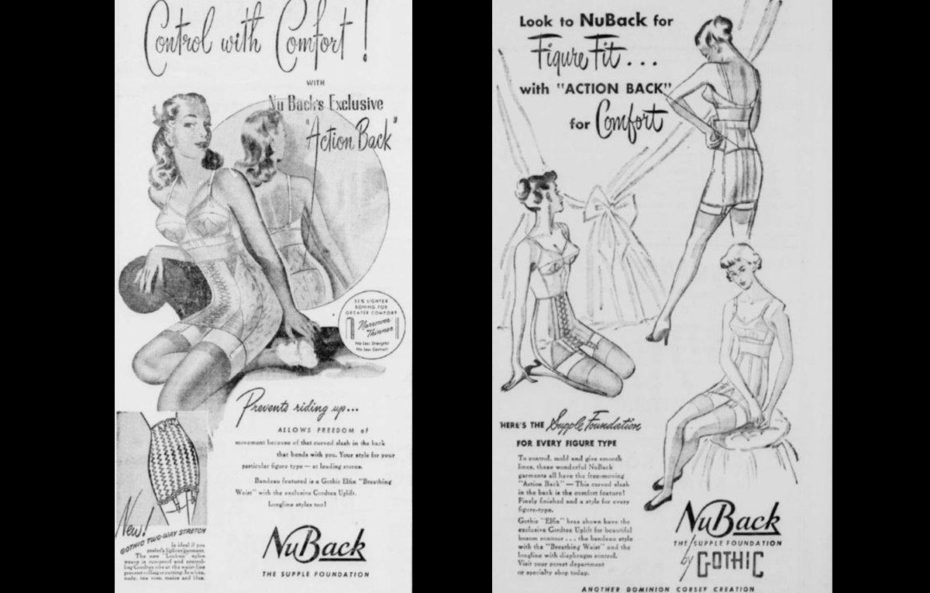

So what was it, this controversial image that caused such a scandal? Unfortunately, there is no copy either in the correspondence file or in the Fashion, Textiles and Clothing Collection of which it is part, and no reproduction of the image has been discovered elsewhere to date. But if we look at Dominion Corset advertisements that appeared in newspapers before and after the morality campaign, its effects seem evident.

An ad published in the fall of 1948 shows a model very much in “pin-up” mode, a young woman staring boldly and alluringly at the viewer, flaunting her curves. But by February 1949 the images had been considerably toned down: the models, portrayed from further away and more impressionistically, are less voluptuous and often avert their gaze. Modesty had triumphed – but for how long?

FURTHER READING

SOURCES

The correspondence file on which this article is based is kept in the Fashion, Textiles and Clothing Collection (C609) of the Textual Archives Collection at the McCord Museum, file number C609/A2.5. It may be consulted by making an appointment with the Museum’s Archives and Documentation Centre.

Valois, Monsignor Albert, “Il doit y avoir des limites…,” L’Action nationale (March 1946), pp. 241-244.

MONOGRAPHS

Laboratoire d’ethnologie urbaine de l’Université Laval, ed. Jean Du Berger and Jacques Mathieu, Les ouvrières de Dominion Corset à Québec, 1886-1988, Sainte-Foy, Presses de l’Université Laval, 1993, 148 pp.

Lapointe, Mathieu, Nettoyer Montréal. Les campagnes de moralité publique, 1940-1954, Quebec City, Septentrion, 2014, 395 pp.

Namaste, Viviane, Imprimés interdits. La censure des journaux jaunes au Québec, 1955-1975, Quebec City, Septentrion, 2017, 240 pp.

Rutherford, Paul, A World Made Sexy: Freud to Madonna, University of Toronto Press, 2007, 371 pp.