The Conservation of Bandolier Bags: Keep Calm and Bead on

Bandolier bags from the Indigenous Cultures collection are carefully examined and restored.

May 3, 2020

The permanent exhibition Wearing our Identity – The First Peoples Collection highlights a diverse selection of objects from our Indigenous Cultures collection. Many of the objects are comprised of organic materials such as hide, fur, and wool, often in combination with inorganic materials such as metal and glass. The sensitivity of the materials found in the majority of the artefacts chosen for the exhibition necessitates an annual rotation of these fragile objects in order to minimize damage from over-exposure to light and other environmental conditions.

As an objects conservator at the McCord Stewart, I have worked on the yearly preparation of these rotations. Through this, I have had the opportunity to work on several versions of the same type of object, allowing me to study their similarities by comparing material and aesthetic choices, as well as technical details of their construction and deterioration. One such example is the museum’s collection of beaded bandolier bags. The bags have been hand sewn from wool and cotton fabrics, and are embellished with colourful beadwork. They illustrate the creative and technical skill of the women artists who created them.

Bandolier bags originate from Indigenous groups in the Eastern Woodlands/Great Lakes area and are modelled after the shoulder bags European soldiers used to carry ammunition. Earlier versions were worn for ceremonial purposes and did not have pockets. Considered items of prestige, they were occasionally traded between communities.

The majority of the bags were produced from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, though they continue to be made today. Sewn from trade cloth—wool, cotton and velvet—these bags are covered almost in their entirety with beadwork, using combinations of appliqué and loom-woven techniques.

BEADING TECHNIQUES

Appliqué beadwork, or spot stitching, involves stringing seed beads on one thread, and then laying them in place. The design is secured by tacking down the beaded thread directly onto a fabric backing with small stitches at intervals of three or four beads. This type of technique lends itself to curvilinear designs and is often used in the creation of floral patterns.

Loom-woven beadwork is created on a wooden loom, using a technique similar to weaving textiles, and produces geometric motifs. The weaver secures a parallel series of warp threads to the ends of the loom, and then weaves the beads through the warp with weft strands.

TREATMENT

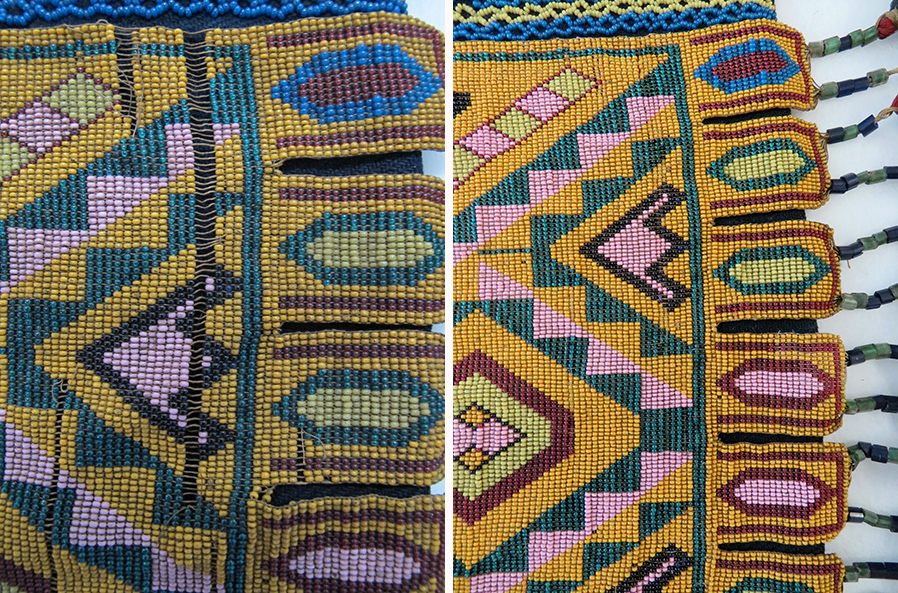

The bandolier bags treated for this exhibition date from approximately 1860-1925. For the majority of the bags, an accumulation of dust lent the beadwork a dull appearance. In some instances, a thick layer of grime adhered to the beads imparted a grey tinge to the colours of the glass. The first step in cleaning the bags was to vacuum them using a low suction setting and a mesh screen as a barrier to avoid accidently removing any loose material such as unattached beads. Following this, the beadwork was cleaned with saliva on cotton swabs (a secret tool in the conservator’s kit!), then rinsed with deionized water-dampened cotton swabs. The marked difference between cleaned and uncleaned beads is very satisfying!

The wool is susceptible to damage from insects such as clothes moths; the resultant holes in the cloth are unsightly and can weaken the fabric support underneath the beaded panels. In such instances, a backing in a similar shade to the original wool is inserted behind the holes and secured with discreet stitching.

The cotton fabric and beading threads are prone to yellowing and the threads often become embrittled due to the process of oxidation. The beadwork contains thousands of glass beads, which makes the bags quite heavy and puts stress not only on the seams connecting the strap, but also on the warp and weft threads. Some of the beading threads have broken and, as a result, some beads have come loose or are missing. This creates gaps in the beadwork that are quite noticeable and interfere with a visual reading of the beaded motifs.

In addition to the aesthetic issues with the missing beads, the structure of the loom-woven beading is compromised as the areas of loss and broken threads create the risk of more bead losses and place more stress on the remaining intact threads. To counter this, replacement warp and weft threads and new beads were woven into the existing formation, using fine silk thread.

Throughout the process, I drew diagrams outlining the location of the replacement beads and threads, if, for some reason, it is decided in the future to remove the treatment.

Upon completion of the treatments on the various bags, the beadwork regained its vibrancy in the colours chosen for the motifs. The previously unstable sections in the beadwork were now secure and, with the replacement beads in the woven beadwork, the geometric designs were once again visible as a whole.