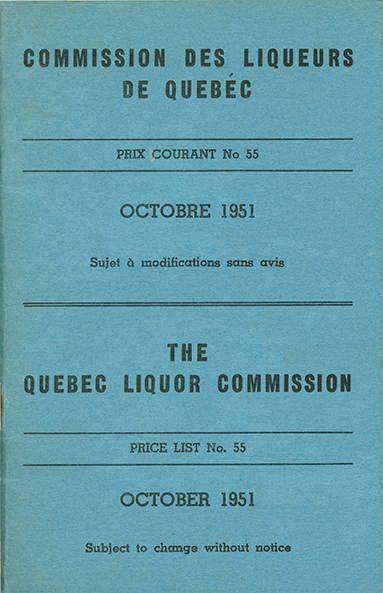

The SAQ Celebrates 100 Years

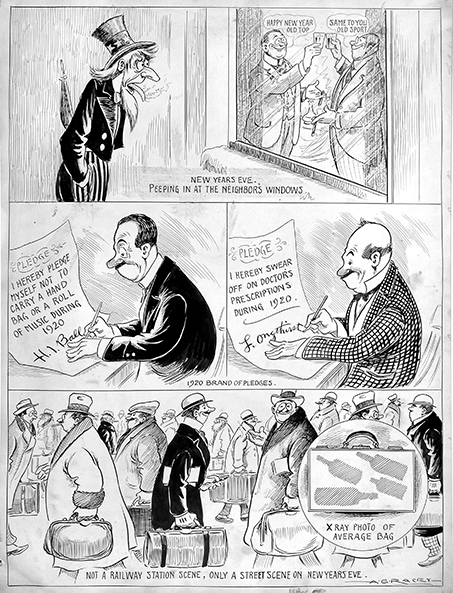

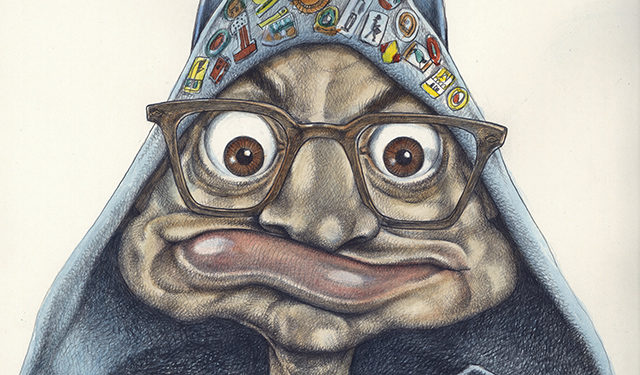

With the help of cartoons from the collection, revisit the historic events that led to the founding of the Quebec Liquor Commission.

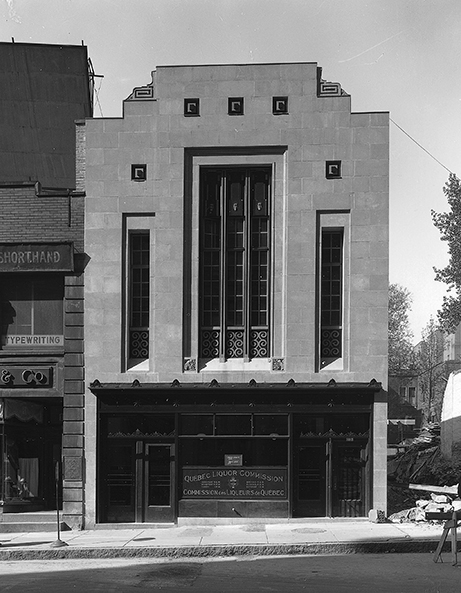

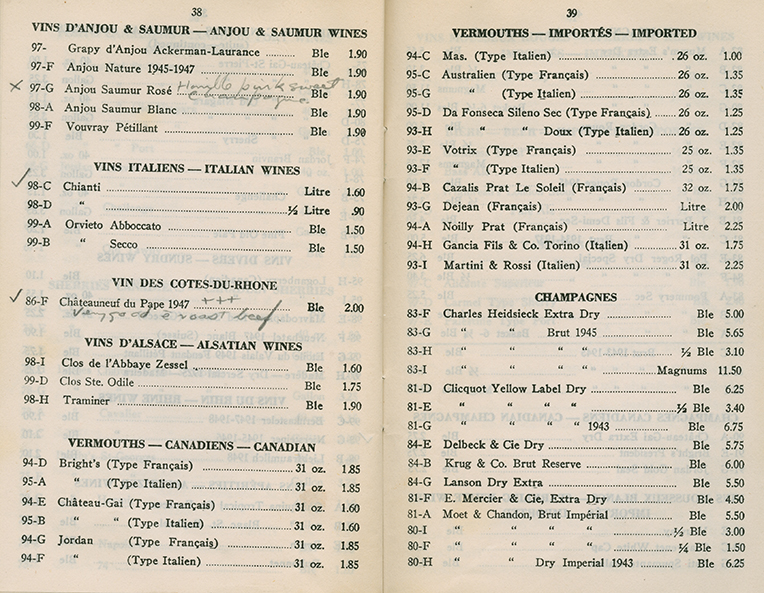

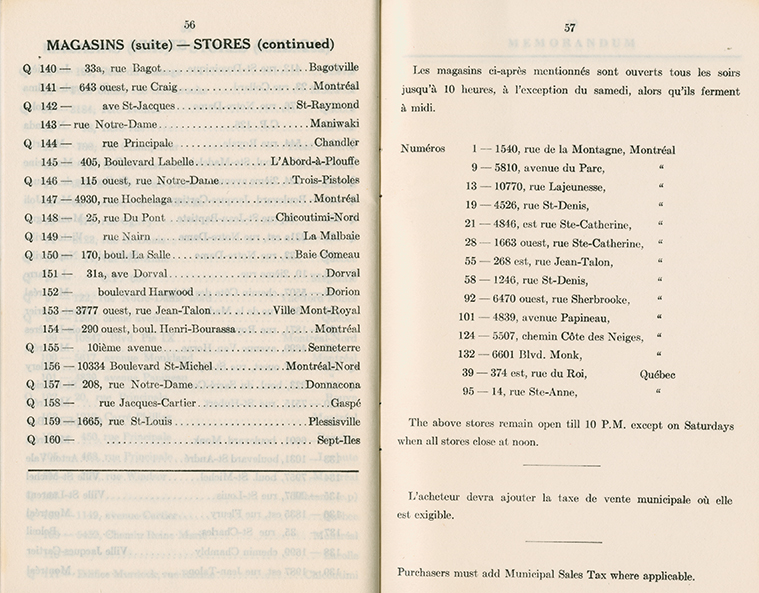

On May 1, 1921, with alcohol banned in the United States and most Canadian provinces, Quebec launched a bold social experiment by creating the Quebec Liquor Commission, now known as the SAQ (Société des alcools du Québec). Inspired by Sweden’s state-run system, it gave the government a monopoly on the importation, distribution and sale of wine and spirits. Though controversial at first, the SAQ has become an integral part of popular culture and the Quebec way of life. What follows is a look at Prohibition and the SAQ through selections from our collections.

FROM THE TEMPERANCE MOVEMENT TO PROHIBITION

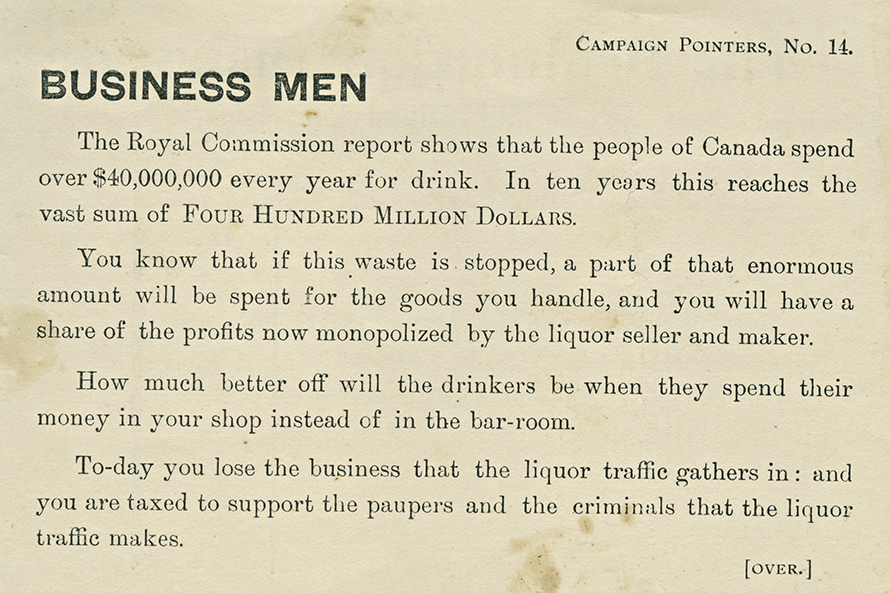

Although controversies concerning the sale and excessive consumption of alcohol date back to New France, a social movement strongly advocating for moderation or total abstinence with regard to alcohol became increasingly popular in 1840s North America. Associated with powerful religious revivals amongst both Catholics and Protestants, the temperance movement demonized alcohol, presenting it as the source of most social ills and individual problems, including poverty, conjugal and family violence, absenteeism and mental illness.

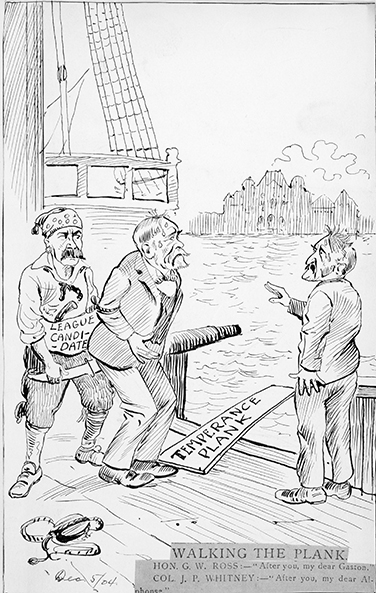

However, having quickly found that mass conversions often produced negligible, temporary results, temperance supporters began advocating for government-backed measures to ban alcohol. They formed coalitions like the Dominion Alliance for the Total Suppression of the Liquor Traffic (1876) and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU, 1874), one of the first organized groups to encourage women’s involvement in the public sphere and ultimately their right to vote in order to improve society.

Prohibition, however, was not very popular amongst politicians, who saw it as a radical measure that went against the desires of vast segments of the population and could cause them to lose an election.

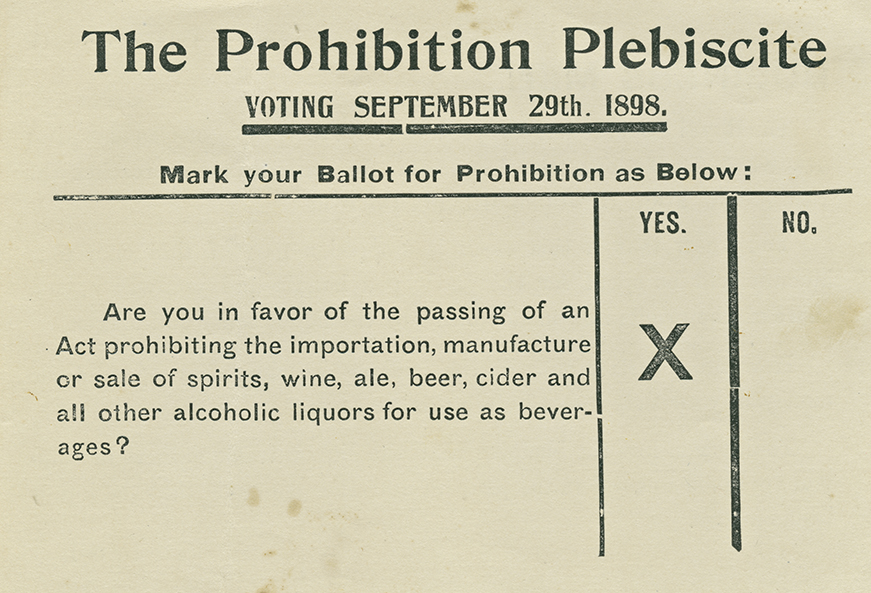

In 1898, Wilfrid Laurier, Canada’s new Liberal Prime Minister, kept his election promise of holding a national plebiscite on prohibition. Although a slim majority of the votes cast were in favour, turnout was low and the results varied among provinces: Quebec voted decisively against prohibition. Laurier decided not to do anything.

Existing laws enabling the “local option” remained, which meant that municipalities or counties could institute prohibition within their territory if a sufficient percentage of the population requested it.

The temperance movement gained popularity during the First World War, as it was associated with the idea of moral sacrifice in the service of victory and the fight to avoid wasting resources like grains. As the war progressed, most provinces voted in favour of prohibition and, by the end of the war, the United States supported this choice by passing the 18th amendment, launching the Prohibition era (1920-1933), known as the “Noble Experiment.” Under Premier Lomer Gouin, even the Quebec government enacted a ban on alcohol in 1918, although it allowed exceptions for religious (sacramental wine), medicinal and industrial purposes.

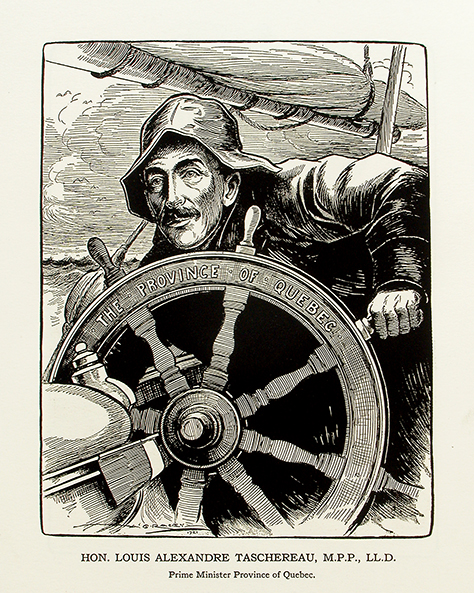

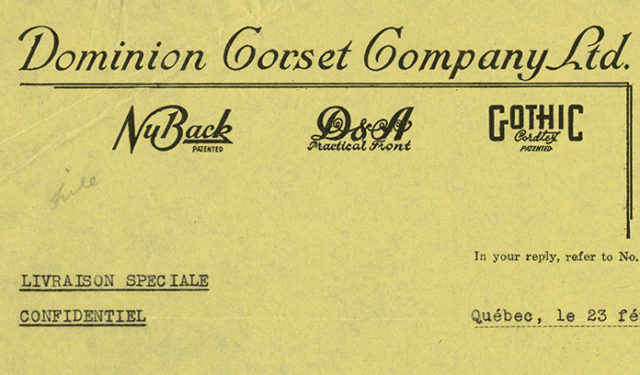

USING STATE CONTROL TO COUNTER THE NEGATIVE EFFECTS OF PROHIBITION

To French-speaking Canada and other segments of the Canadian population, prohibition seemed excessive, oppressive and unrealistic. Many Francophones saw it as an expression of Anglo-Protestant or American Puritanism. Even the Catholic Church was historically opposed to the measure, recommending instead that believers mobilize and voluntarily commit to temperance. When Louis-Antoine Taschereau succeeded Gouin as Premier in 1920, he saw the adverse effects generated by prohibition: smuggling, ordinary citizens breaking the law, and the abuse of the exception for medicinal purposes.

Seeking a solution, Taschereau was inspired by the proposal of Judge Henry George Carroll, who had suggested following Sweden’s example of a state-run monopoly for the sale and distribution of alcohol. In 1921, Taschereau created the Quebec Liquor Commission (QLC), though he exempted beer from the new system, as he did not want to upset working class people, brewers and tavern owners. A bold initiative, the QLC was the first such organization in North America.

It angered alcoholic beverage importers and distributors and was controversial among the more intransigent Catholics and nationalist critics like those at Le Devoir newspaper. Nonetheless, once things settled down, it was generally accepted by the population and eventually copied by most of the other Canadian provinces, who saw it as an interesting source of tax revenues.

Montreal — SIN CITY

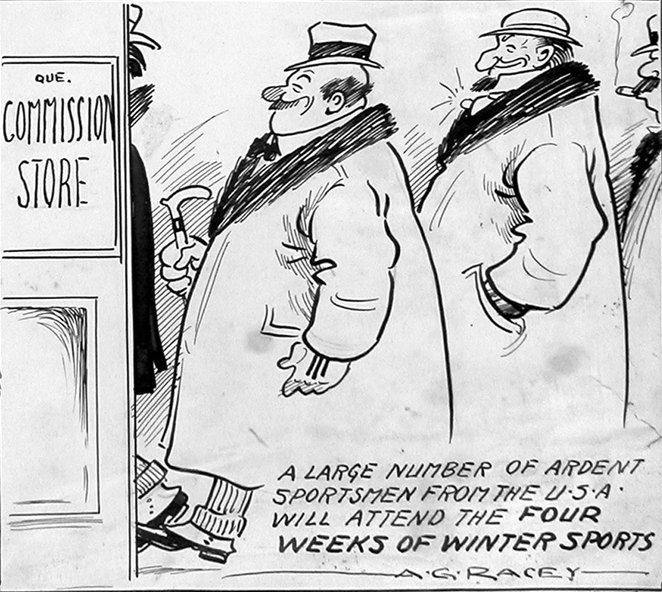

The contrast between the United States under Prohibition and Quebec’s more liberal system drew many thirsty Americans to Montreal, making it a new “sin city” for the Jazz Age and giving it a reputation for hedonism that it maintains to this day. The cartoonist of the Montreal Star, Arthur Racey, alluded to this in his forecast for the year 1923, which depicted chic American “sportsmen” filing into the Liquor Commission.

ENGLISH MONTREALERS CRITICIZE PROHIBITION

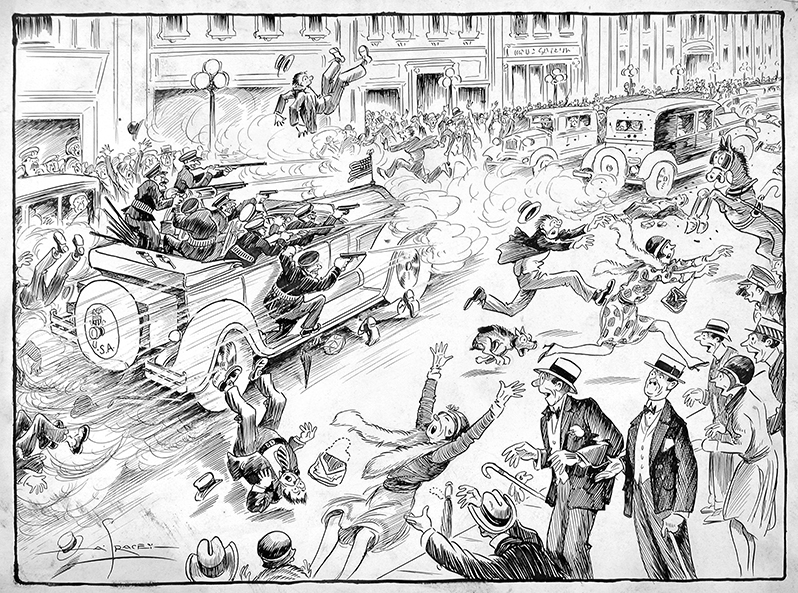

French-speakers were not the only ones against prohibition. Arthur Racey, for one, was not at all fond of this radical measure or its harmful side effects. In 1929, he criticized American police officers entering Canadian territory in pursuit of bootleggers as well as the violence associated with the clampdown on alcohol in the United States, which he pictured in the middle of St. Catherine Street, the heart of Montreal’s shopping district.

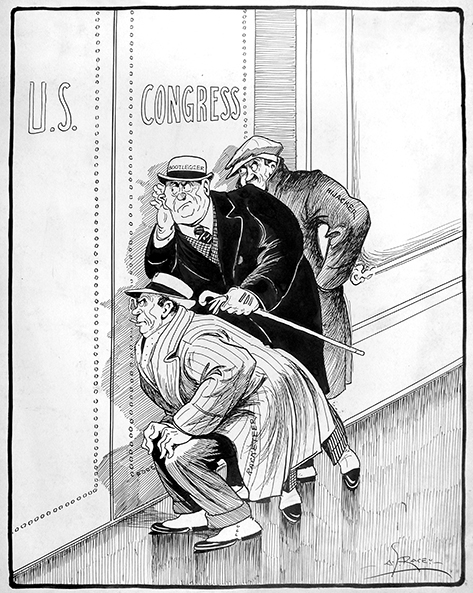

In 1933, to underscore how Prohibition had fostered the growth of organized crime in the United States, one Racey cartoon showed concerned gangsters listening at the door as Congress discussed striking down the measure.

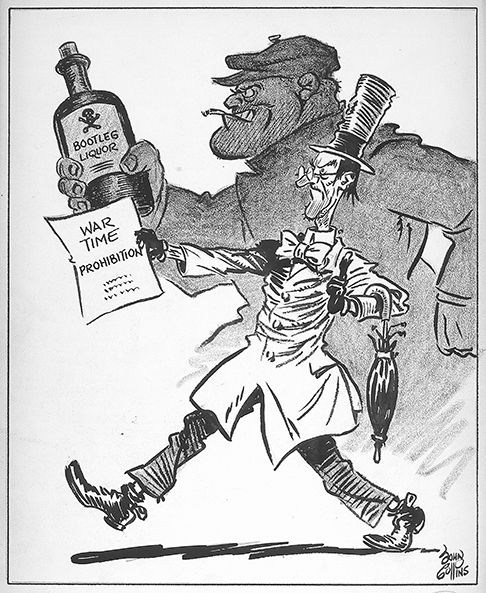

In The Gazette, John Collins echoed the same theme in 1942, drawing a Puritan proponent of wartime Prohibition with the shadow of a menacing gangster running bootleg alcohol.

THE SAQ IN POPULAR CULTURE

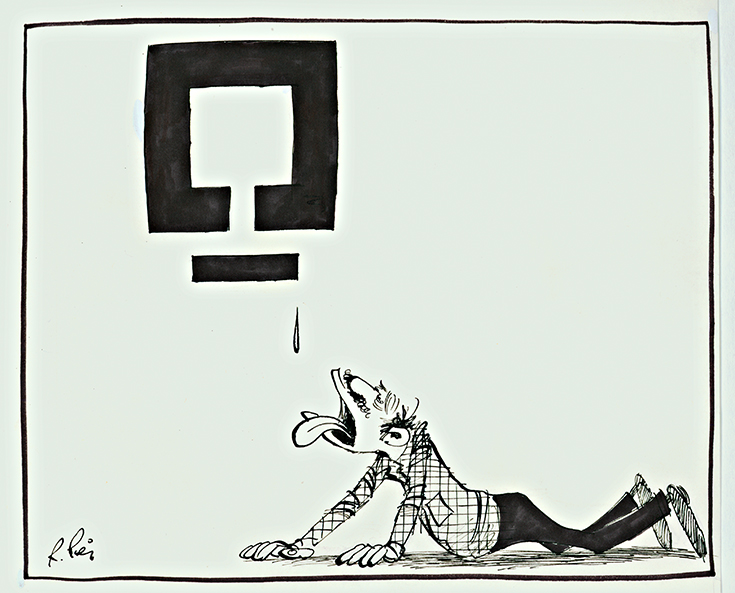

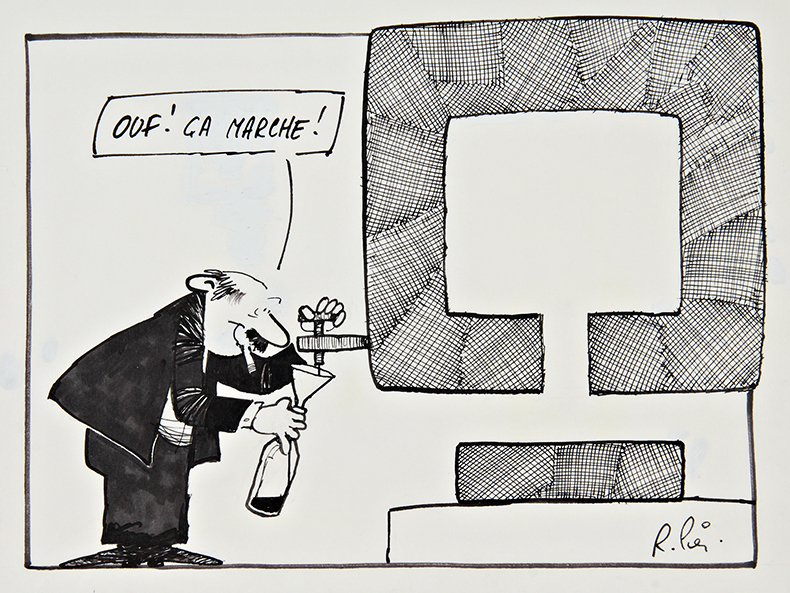

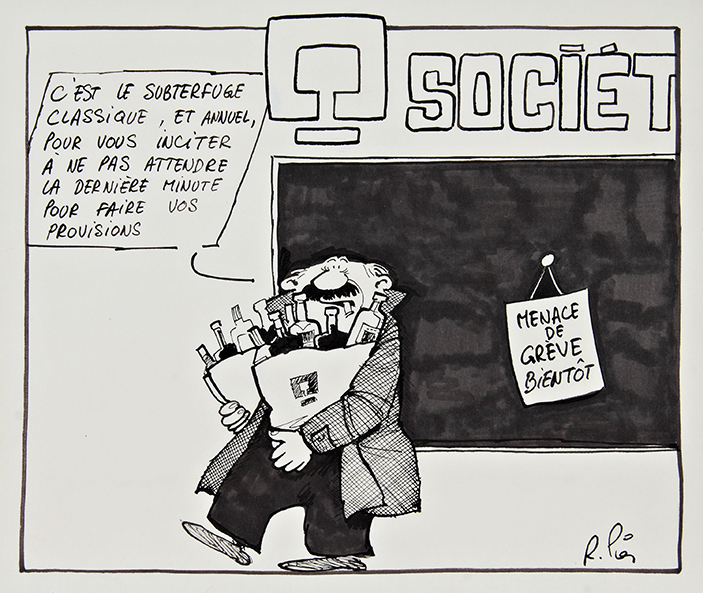

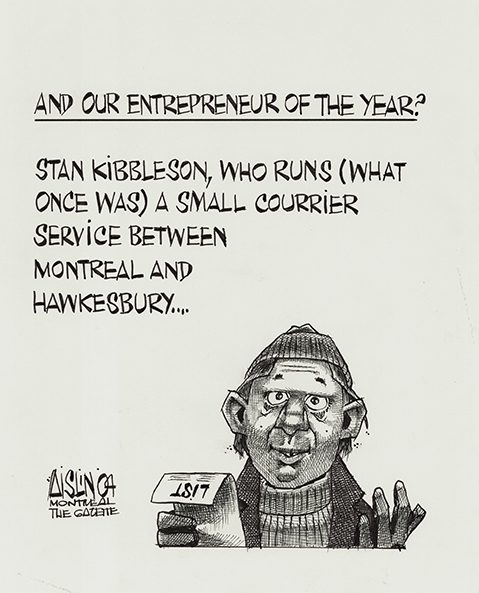

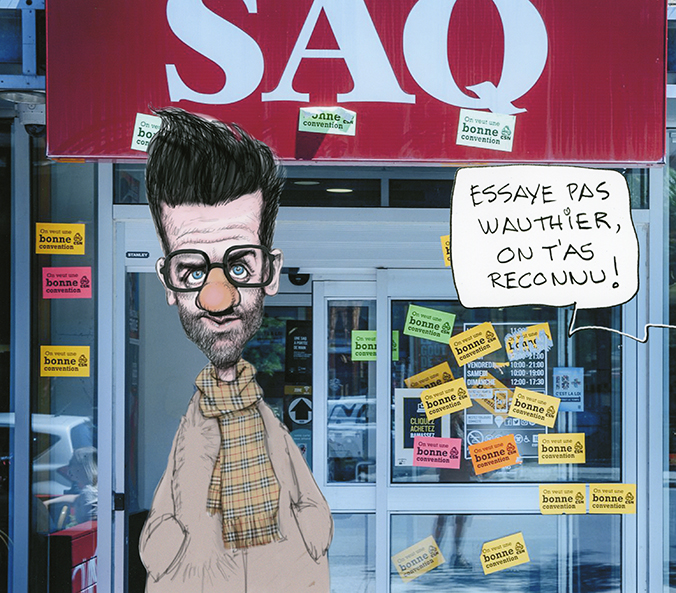

In more recent history, the McCord’s cartoon collection clearly illustrates the SAQ’s position in popular culture and the daily lives of Quebeckers. Recurring strikes—and threatened strikes—have provided cartoonists with plenty of comic inspiration.

Other current events, such as the legalization of cannabis and the COVID-19 pandemic, have also generated funny cartoons featuring the SAQ.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Craig Heron, Booze: A Distilled History. Toronto: Between the Lines Press, 2003.

Marcel Martel, Une brève histoire du vice au Canada depuis 1500. Quebec City: Presses de l’Université Laval, 2015.

Robert Prévost, Suzanne Gagné and Michel Phaneuf, Histoire de l’alcool au Québec. Montreal: Stanké, 1986.

Robert Rumilly, Histoire de la province de Québec – Alexandre Taschereau (vol. XXV). Montreal: Chanteclerc, 1952.

Bernard L. Vigod, Quebec Before Duplessis: The Political Career of Louis-Alexandre Taschereau. Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1986.