Finding Space for a Growing Collection

What do a Greek temple, a rifle range, a Stanley Cup champion, and Harry Houdini all have in common?

August 30, 2021

What do a Greek temple, a rifle range, a Stanley Cup champion, and Harry Houdini all have in common? They are all connected in some way with the buildings that have housed the collections of the McCord Museum over the years.

A GREEK TEMPLE ON THE MOUNTAIN: THE MCCORD MUSEUM COLLECTION’S FIRST HOME

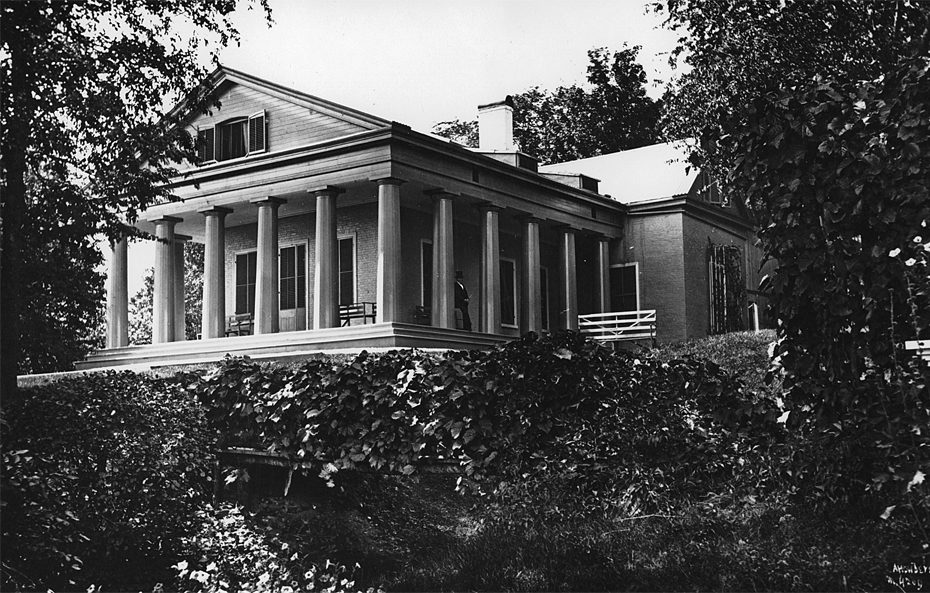

In 1838, Montreal lawyer John Samuel McCord (1801-65) built a summer home on the side of Mount Royal, overlooking the city. Named Temple Grove, this distinctive building with large Doric columns on three sides was located just south of where Côte-des-Neiges Road and Cedar Avenue now intersect.

According to his son, David Ross McCord (1844-1930), John Samuel explained his choice of design by saying, “I looked upon the site I had selected for my country home—and its dominant position—and said to myself: the Greeks would have built a Temple—and so shall I.”1 The McCord family moved there permanently in 1844.

David Ross McCord was a lawyer by training, but he also had a great passion for the past. By about 1880, he had begun to collect objects connected with the history of Canada and, over time, his collection began to intrude on the living space of Temple Grove.

In 1914, a journalist described McCord’s home as practically bursting at the seams with relics from the past, writing “‘Temple Grove’ is by no means a small house, but it is packed almost from floor to ceiling with many hundreds of souvenirs at which the authorities of the British Museum would jump.” With every room on the ground floor filled with objects, “…the family had been driven for house room to the upstairs apartments. Even these are being invaded by relics, and the family, retreating before them, will apparently soon find itself on the roof, so rapidly is the collection growing.”2 At this time, David Ross McCord was actively searching for an institution willing to provide a building to house his collection, which he had already named “The McCord National Museum.”

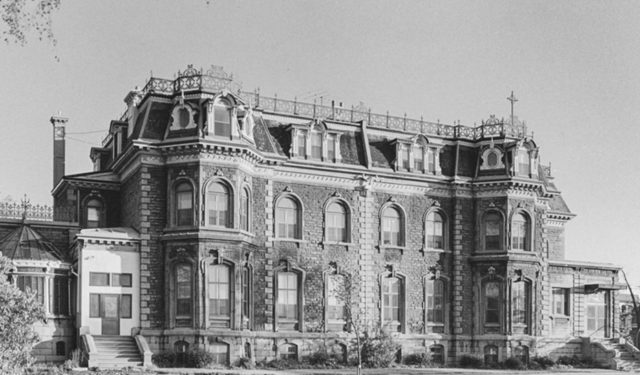

DILCOOSHA: JESSE JOSEPH’S “HEART’S DELIGHT”

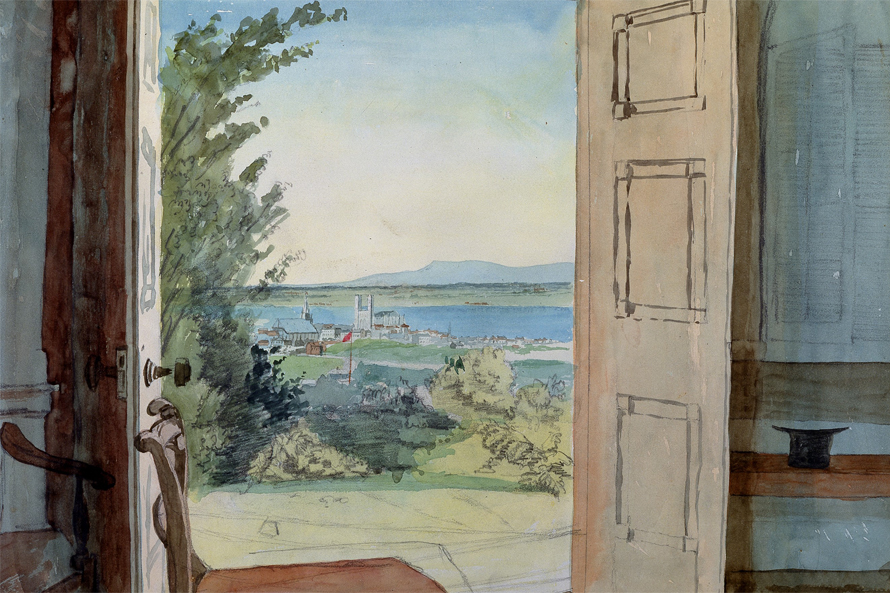

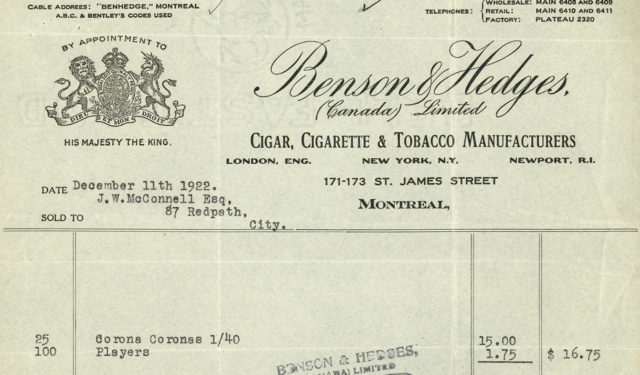

David Ross McCord donated his collection to McGill University in 1919 and, early in 1921, the objects were transferred from Temple Grove to the Joseph House near the corner of Sherbrooke and McTavish streets, where the McLennan Library now stands.

The Museum was then opened to the public for the first time on October 13 of that year. The house was constructed in 1865 for Montreal businessman Jesse Joseph (1817-1904), who named it Dilcoosha, which means “Heart’s Delight” in Hindustani.

During World War I, Dilcoosha served as the headquarters of McGill’s contingent of the Canadian Officers Training Corps (COTC). In 1913, not long after the founding of the McGill Corps, Honorary Lieutenant-Colonel Jeffrey Burland had furnished the building as an armoury, even fitting it out with a miniature rifle range! Located in the attic, the range was about 30 yards long (27.4 metres).3 Evidence of this function remained in the southeast attic wall, which was still “riddled with lead slugs” in 1954, while the ceiling above was “splintered” from ricocheting bullets.4

At first, Dilcoosha’s many rooms, large attic, and basement storage vault were spacious enough for the approximately 10,000 items in the collection. Donations were numerous, however, and it was not long before the Museum’s collection began to outgrow its accommodations once more!

By 1932, the Joseph House was insufficient for the needs of the Museum. Unfortunately, the financial strains of the Great Depression did not help matters for the Museum, which McGill closed to the public beginning in 1936. In 1954, a large crack in the west wall of the building, stretching from roof to foundation, had widened to the extent that McGill authorities condemned Dilcoosha to be demolished.

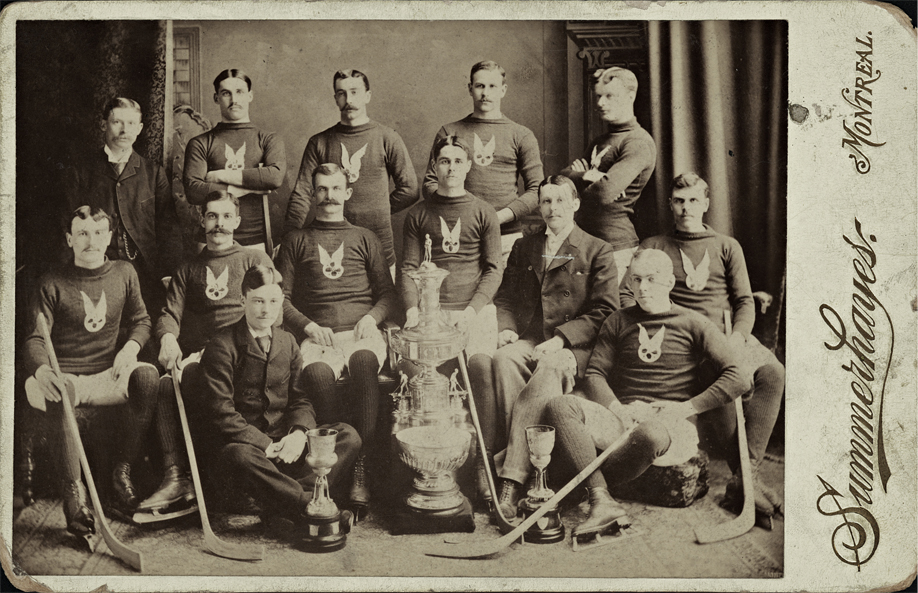

THE A. A. HODGSON HOUSE, HOME OF A STANLEY CUP CHAMPION

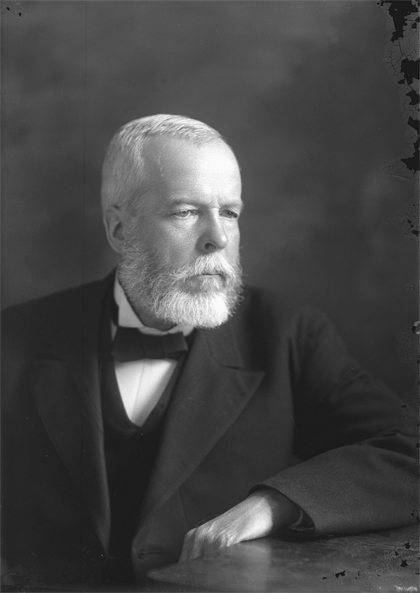

The McCord Museum moved to the Hodgson House, in November 1954. Archibald Arthur Hodgson (1869-1960) was a Montreal businessman who had donated his home on Drummond Street (at the corner of today’s Doctor Penfield Avenue) to McGill.

In his youth, Hodgson was well known for his proficiency in sports, particularly lacrosse, football, and hockey with the Montreal Amateur Athletics Association. An “outstanding hockey forward” with “a shot that travelled like a bullet,” he was a member of the first team awarded the Stanley Cup trophy, in 1893.5

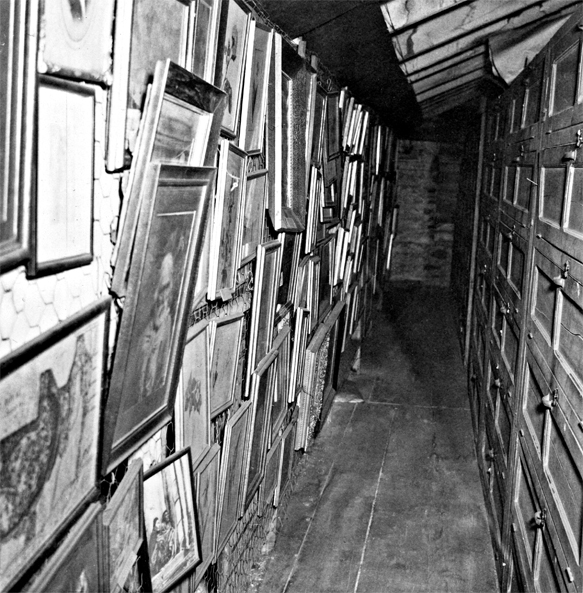

Moving the collections to the Hodgson House had been necessary, because of the impending demolition of Dilcoosha, but it was a tight fit. According to Isabel Dobell (1909-1998), hired in 1955 to take an inventory of the collection,6 every corner of the building “…was crammed with McCord artifacts, many still in the boxes and packing cases in which they had been moved. Even the bedroom cupboards and utility rooms were filled to overflowing” and “in several bathrooms even the baths had been covered with plywood to provide storage space.“ Framed maps and paintings were stored in the attic, which Dobell described as “…not an especially fortunate storage space, since the temperatures were close to freezing in winter and climbed to over 33 C in the summer heat.”7 In an internal document, an anonymous staff member described the attic as “a hell of a place for anything except bats!”8

MCGILL STUDENT UNION BUILDING: HOME OF THE MCCORD MUSEUM FOR MORE THAN FIVE DECADES

In the Hodgson House, research was possible by appointment and a one-room gallery, created in 1960, featured small temporary exhibitions of the museum’s objects. By the mid-1960s, a larger space became available for the Museum. In planning to replace the Student Union building with the construction of a new University Centre on McTavish, McGill was able to free up the old building at 690 Sherbrooke Street for the Museum.

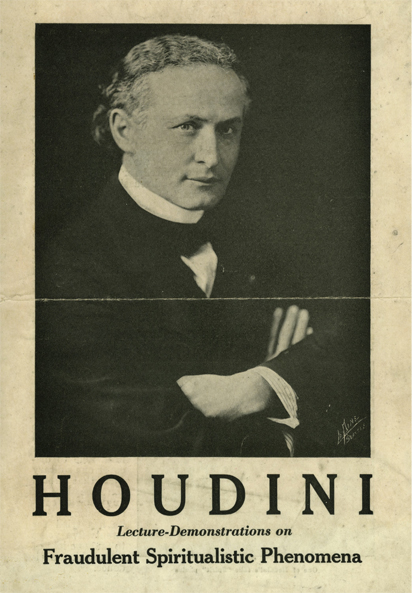

Many generations of students had passed through the doors of the Student Union building, constructed in 1906. The third floor ballroom had been host to many different events over the years. On one memorable occasion, in October 1926, the celebrated illusionist Harry Houdini spoke to McGill students on the subject of fraudulent spiritualists.9

In 1968, the collections moved into the newly renovated building. For the first time, there was enough room to house the several hundred thousand photographs and negatives of the Notman Photographic Archives. Because of the lack of space at the Hodgson House, they had been stored separately in the basement of the Redpath Library since their acquisition in 1956. Open to the public once more in 1971, the McCord Museum was yet again in need of more storage space by 1988. After the collections were moved across town to temporary quarters, 690 Sherbrooke Street was entirely renovated for a second time. Enlarged with a new extension at the rear, it reopened in 1992, in time for Montreal’s 350th anniversary.

Today, nearly thirty years later, the McCord Museum’s collections, supplemented by mergers with the Stewart Museum (2013) and the Fashion Museum (2017), are straining at the seams of their storage spaces. The Museum is planning the construction of a new museum building at the back of the current one, extending westward onto Victoria Street.10 This will enable the McCord-Stewart Museum to continue celebrating Montreal’s past—well into the future!

NOTES

1. McCord Family Papers (MCFP), file 2065, 15 August 1916.

2. C. Lintern Sibley, “An Archipelago of Memories” Maclean’s Magazine, March, 1914, p 7.

3. The Gazette (Montreal), Saturday, October 11, 1913, p 10.

4. Alice Johannsen Turnham “The Passing of a Landmark,” The McGill News, Autumn, 1954, p 3.

5. The Gazette (Montreal), Thursday, November 24, 1960, p 39; D. A. L. MacDonald, “Turning Back Hockey’s Pages,” The Gazette (Montreal), Thursday, January 17, 1935, p 14. Hodgson and his teammates were able to defend their title the following year, winning the first Stanley Cup championship series in 1894.

6. Isabel Dobell would later become the Director of the McCord Museum. See Kathryn Greenaway, “Isabel Dobell will be remembered for contribution to local history,” The Gazette (Montreal), Tuesday, April 28, 1998, p 13.

7. Isabel Dobell, “Buried Treasure,” in Margaret Gillett ed., A Fair Shake, p 140.

8. McCord Museum Weekly Report, May 20-27, 1957, Red Binder, McCord Institutional Files

9. The Gazette (Montreal), Wednesday, October 20, 1926, p 7.

10. See https://www.musee-mccord-stewart.ca/en/montreal-new-downtown-museum/