Feeling Exposed

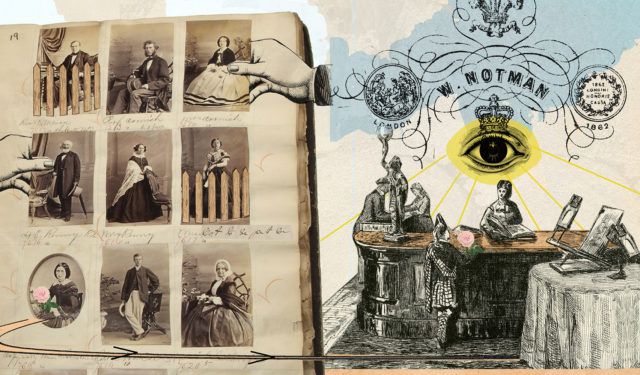

Not to Be Sold: Privacy at Notman’s Studio or Controlling One’s Image in the 19th Century (Part 2 of 6).

June 28, 2022

A wide range of sitters registered concerns about the circulation of their photographs, but the risks for young women were particularly conspicuous. Victorian society idealized the “Angel in the House,” the modest, selfless, usually white, woman who remained in the domestic sphere, leaving the public arena to men.

Just as it was considered unseemly for women themselves to be too much in the public eye, popular literature in the mid-19th century frequently highlighted the risks posed to young women’s reputations if their images circulated too widely or fell into the wrong hands. This may help explain why several young women are among those whose portraits have been restricted.

| You missed the beginning of this series? Here is the first article Welcome to the Studio |

In a short romance written by Ella Rodman in 1862 and published in a popular American magazine, a young man and young woman are alone in a drawing room at the end of a party on the eve of his departure for war. As a parting gift, he asks for a photograph of her that had been admired by those gathered earlier in the evening. The young woman is clear that this would violate her understanding of who should possess her image: “Miriam took it from him with downcast eyes, turning away as she said, ‘Do not ask me for these things, Gilbert—I cannot break through my rule, which is to bestow them only on my lady friends.’”1

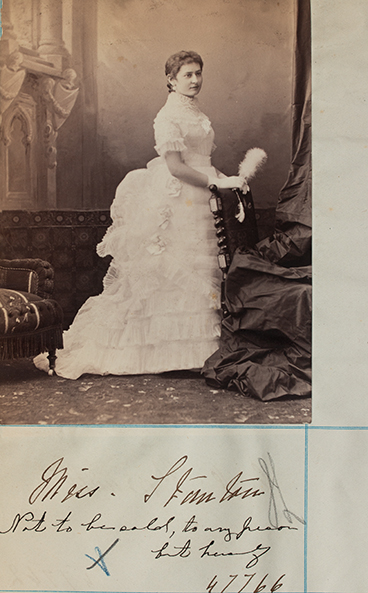

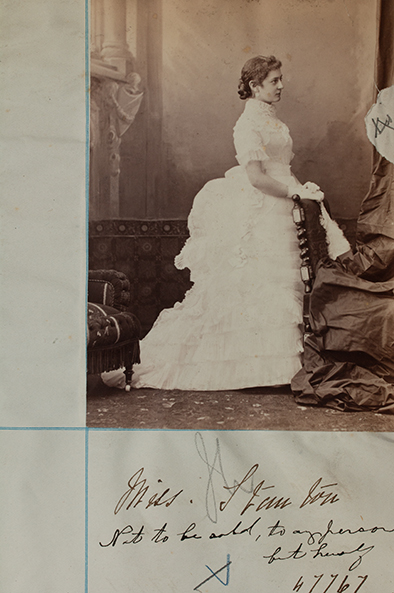

MISS STANTON

In 1878, the fashionable Miss Stanton posed for a series of elaborate full-length portraits and a headshot at Notman’s studio and instructed the studio not to sell copies to anyone else.

Miss Stanton might have been taking precautions against unwanted attention by preventing her images from circulating in contexts that might incite men’s desires. Alternatively, Stanton might have been restricting the circulation of these images to a particular viewer whose desires she very much hoped to incite.

What is striking in Stanton’s case is that she is the one managing her own image as a young woman: the restriction directs the studio to sell to no one but herself. In a shift from Victorian to more modern norms, she does not hide her wishes behind even the pretense of anyone else serving as guardian of her propriety.

MISS MOLSON

Stanton’s restriction contrasts with the one appended to four portraits of Miss Molson, whose images were not to be sold to anyone other than members of her prominent family.

The Molson family was well known for its namesake brewery and bank and the sitter may be Eva Molson, who had sat for Notman as a child. Miss Molson looks rather bored in her high-necked bodice and curly hair pinned up in the headshot and plumed hat and fur coat in the half-length version. However, as the literature of day made clear, it was not so much the content of a young woman’s portrait that could be risqué, but its sheer existence in the wrong context.

PHOTOGRAPHY AND SELF-PRESENTATION

We can relate these historical case studies to contemporary concerns regarding privacy and social media photography. For example, the fear of unwanted attention exemplified by Rodman’s story and the pressure to be identified with norms both figure in the contemporary discourse regarding the concepts of privacy that inform the use of photography on social media.

Like Victorians, who worried about the unrestricted circulation of their images, we worry about the unfettered access that corporate interests have to our photographs and data. Moreover, whereas Victorians developed concerns about photography and self-presentation, today’s social media accounts are largely informed by aesthetic standards and shaped by public scrutiny.

NOTE

1. Ella Rodman, “A Daguerreotype in a Battle,” Peterson’s Magazine (Philadelphia) 44 (1862), 187-190.

The series Not to Be Sold: Privacy at Notman’s Studio is supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.