Crafting personal identity at the Studio

Not to Be Sold: Privacy at Notman’s Studio or Controlling One’s Image in the 19th Century (Part 5 of 6).

June 28, 2022

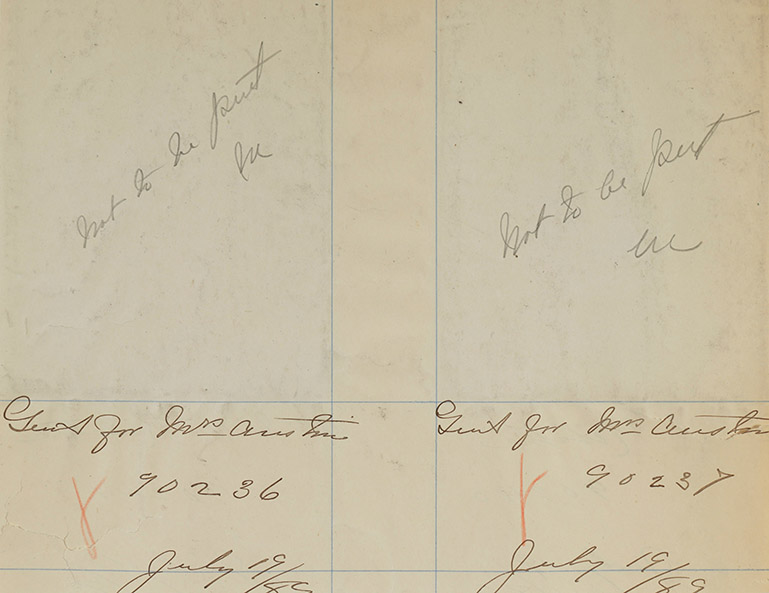

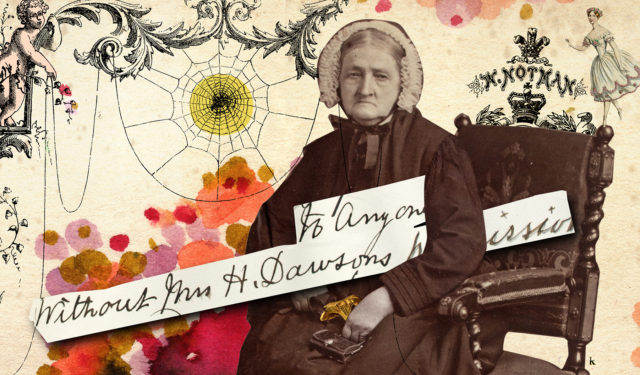

Amongst the most heavily restricted photographs in Notman’s archives are a few remarkable portraits of an unknown non-gender conforming individual. Either this unidentified sitter or the Mrs. Austin who apparently commissioned the images specified that these portraits were Not to be put in, meaning that they were not permitted to appear in the studio’s Picture Book.

The studio’s staff meticulously followed this directive inscribed beside the blank spaces where the prints should have been. Studio records reveal that four photographs of this subject were taken, but that only three have survived in negative form.

| You missed the beginning of this series? Here is the first article Welcome to the Studio |

CONCEALING TRACES OF THE SITTER'S MASCULINITY

At first glance, these photographs look like conventional portraits of a Victorian woman in a high-necked dress; however, the sitter’s hair is cropped short and the bust line of their bodice lacks fullness.

The full-length portraits, in particular, seem to have been strategically staged to conceal traces of the sitter’s masculinity. In both of these images, the sitter’s hands have been obscured, presumably to disguise their size. In one full-length portrait, for example, the sitter reclines on an ornate chair with both hands behind their head. In both images, the feet have also been made to appear smaller or slimmer by one of the studio’s technicians, who carefully retouched the negative.

PERSONAL IDENTITY AT RISK

These photographs point to a strong desire to affirm one’s identity through photography. Their concealment testifies to the conservative tenor of Victorian gender norms as well as the risks that authentic public presentation posed for so many during this era.

British cross dressers Ernest Boulton and Frederick Park, better known as Stella and Fanny, for example, were arrested in 1870 while dressed as women in public.1 It was one thing for the men to dress as women in a theatrical context, but cross-dressing off stage was undertaken at great risk.

The year before this portrait at Notman’s, Kodak released the first snapshot camera that came preloaded with film. In time, this technology would radically change photography, enabling even those with no technical skill to create images in their homes or anywhere else.

Even if the sitter and Mrs. Austin were aware of and had access to a portable camera, they still chose to come to Notman’s studio. Perhaps they felt safer working directly with Notman rather than sending film off to a commercial developing company such as Kodak. Alternatively, they might have wanted the same type of professional portraiture session afforded to gender conforming clients, making these photographs small acts of resistance and powerful statements of self-affirmation.

#FreeAllBodies

The role that identity politics played in negotiating the private and public uses of studio photography in the 19th century is relevant in today’s social media landscape, where photography is employed to construct and present one’s identity to others.

For example, transgender individuals and those with other non-normative identities use photography to develop body-positive spaces online. Instagram permits users to share their transition journeys, including surgery results. However, Facebook and Instagram have also been known to censor shirtless photographs of transgender men, essentially imposing privacy on those wishing to be seen. In 2015, Courtney Demone, an American transgender woman, responded to the limitations placed on photographs of transgender bodies on Instagram by starting the #FreeAllBodies campaign, which advocates for the right of all to possess ownership of their bodies and its representation.

NOTE

1. See Neil McKenna, Fanny & Stella: The Young Men who Shocked Victorian England, London, Faber & Faber, 2013.

The series Not to Be Sold: Privacy at Notman’s Studio is supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.