Early Heroes of a Closed McCord Museum (Part II)

Learn more about the ties between the McCord Museum and the Stewart family, and the role of Isabel Dobell, the woman who brought the two together!

September 26, 2022

The McCord Museum recently announced a name change to the McCord Stewart Museum in recognition of David M. Stewart, founder of the Stewart Museum, and his wife Liliane, a longtime president of the board. Although the two museums merged back in 2013, the Stewart Museum’s collections were only recently integrated with those of the McCord following the 2021 closure of the museum on St. Helen’s Island. In fact, the McCord Museum’s connections with the Stewart family go back well over six decades, to the time when the Museum was in desperate need of a new, permanent home.

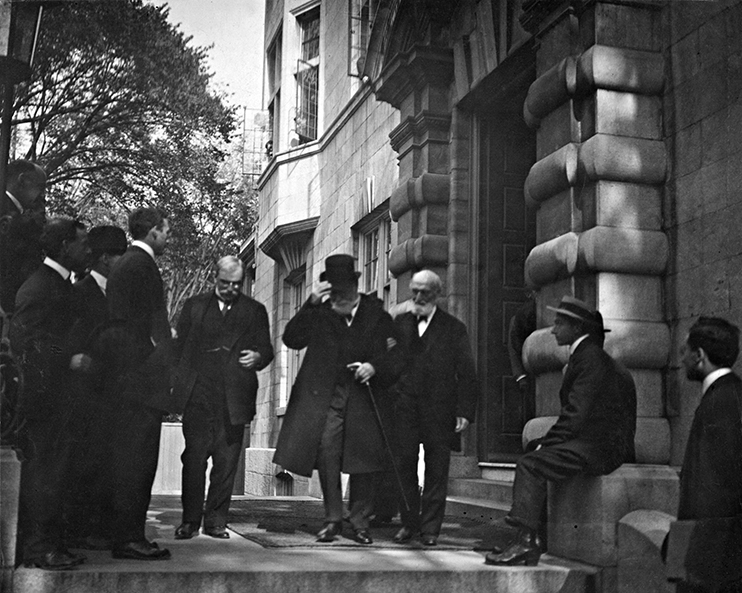

THE McGILL UNION AT 690 SHERBROOKE STREET WEST

The McCord Stewart Museum’s building at 690 Sherbrooke Street West began life in the fall of 1906 as a gathering place for students, known as the McGill Union.1 Designed by McGill Architecture professor Percy Nobbs (1875-1964), the original building was much smaller than it is now. With a footprint of 28 metres in width by only 22 metres in depth, the back wall of the original building ended just behind where the totem pole stands today.

Students entering from Sherbrooke Street were able to obtain meals at a reasonable rate in the dining room on their right, where the Museum Boutique is now. Offices and a smaller luncheon room were on the left. By 1912, there was also a small cigar shop on the right, later known as the tuck shop.

The McGill Union was a space for students to socialize and build a school spirit that reached beyond the divisions of the individual faculties. Accordingly, a large lounge extended across the entire length of the second floor of the building, on the Sherbrooke Street side. Fireplaces added a comforting warmth on cold days, one at each end of the room, and they are still there, behind the walls of the exhibition space!

Five windows, including two large bay windows, brightened the room, which looked out over the McGill Campus and Mount Royal. Students could play billiards in the southeast corner behind the lounge, while those looking for quieter pastimes could read newspapers and magazines or study in rooms in the southwest corner.

A large assembly hall took up most of the third floor, which also featured a music room. The basement, now known as the Victoria Street level, contained a caretaker’s apartment in the northwest corner, where the Canada Life Educational Room is today, and the kitchen supplying the dining room filled the space now occupied by the corridor and Education, Community Engagement and Cultural Programs offices. Offices, locker rooms, laboratories, baths, and an exercise room filled the east side of the basement.

Two members of McGill’s New England Graduates’ Society initiated the McGill Union project in 1903, when they proposed the construction of a Students’ Club.2 Each offered to contribute $5,000 on the condition that at least $65,000 be raised by other graduates of the university. The project gained momentum after Sir William Macdonald (1831-1917), Montreal’s “Tobacco King” and a generous benefactor of McGill University, gave $100,000 to cover the cost of the building and its furnishings.3

The concept of the McGill Union as a social club for students was modelled on other student unions at American and British universities. Student newspapers also document at least two other short-lived clubs for McGill students, established during the 19th century.4

According to McGill’s 1907-08 student calendar, “Membership in the Union is open to all students of the University, without restriction, on payment of the annual fee of $5.00.” Unfortunately, initially only all male students could benefit from the “mental and social recreation” and “enjoy the highest and truest form of student fellowship.”5 Even as late as 1955, according to the Old McGill yearbook, “All male students at the University have full privileges of the Union. Each member of the Women’s Union has limited privileges.”

Despite restrictions on membership, a whirlwind of extracurricular activities enlivened the Union building each semester, many of which included women participants. Numerous societies, committees and clubs held regular meetings there. Dances, debates, mock parliaments and jazz teas are some of the special events that drew male and female students to the McGill Union in 1930.6

ISABEL DOBELL AND THE McCORD MUSEUM

Isabel Marian Barclay (1909-1998) does not stand out amongst the graduates featured in the 1930 Old McGill yearbook. However, the honours student of both History and English would later play a crucial role in the history of the McCord Museum.

Isabel’s energetic personality comes through in the yearbook, in a description of how she is “dashing about” frantically pursuing her degree, hoping to be on time “somewhere, somehow, some day, for something.” Her drive and determination can perhaps be imagined when looking at a Notman portrait of her taken around the age of 18, in 1927.

Her deep commitment to the McCord Museum’s welfare may well have been sparked by her History professor, W. T. Waugh (1884-1932), who was Chairman of the Department of History in 1930. During Isabel’s graduating year, Waugh commented to her, “If you ever want to do anything for McGill, try to see what you can do for the McCord.”7 Isabel Barclay, later Mrs. Isabel Dobell, apparently took his advice to heart.

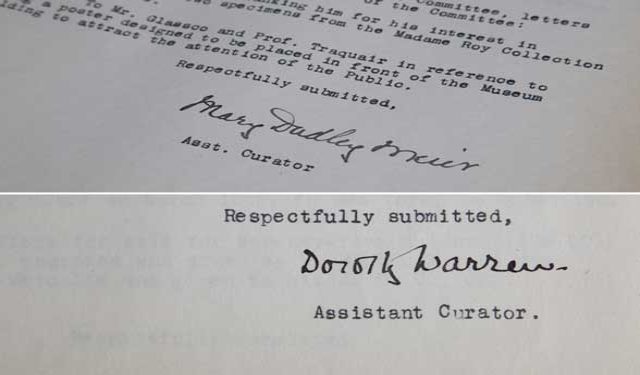

Fast forward 25 years, to the fall of 1955. The Student Union building was busier than ever with the postwar growth of the University, and complaints about the lack of space frequently arose in the McGill Daily newspaper. The McCord Museum’s collections, closed to the public since 1936, were temporarily located in the A. A. Hodgson house on Drummond Street. Isabel Dobell had just been hired to make an inventory of the collection. Dobell later described it as a “wearisome process” whereby the accession number on each object had to be checked against the entry in the accession register to ensure that it was stored in the proper location. Her tedious task was lightened, however, with the “excitement of finding untold historical treasures” in the Museum’s vast collection.8

THE STEWART FAMILY TO THE RESCUE OF THE McCORD MUSEUM

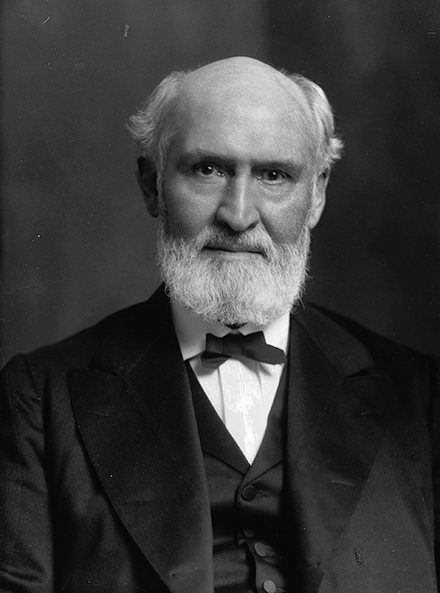

Learning through her inventory that there was a great deal of material in need of conservation and preservation at the McCord Museum, and knowing that there was little hope of obtaining enough funds from McGill University, Dobell decided to act on her own. She approached Walter M. Stewart (1882-1968), the head of Macdonald Tobacco and father of her friend Beatrice (1909-2008).9 Walter Stewart and his brother had inherited the tobacco business on the death of Sir William Macdonald in 1917. Their father David Stewart (1846-1917) had been William Macdonald’s longtime associate at the company, running the day-to-day affairs, and the sons in turn had also joined the firm.

Walter M. Stewart was once described as “…one of the most generous benefactors of this community and probably the least known.” He preferred to give with “gracious anonymity.”10 Isabel Dobell’s initial request for funding was fulfilled, and then some, when Walter Stewart and his wife Mary Beatrice (1883-1971) quietly made funds available to the McCord Museum over the next few years for various conservation projects, the hiring of additional staff members, and staff training.11

Isabel Dobell, in the meantime, advanced through the ranks of the McCord Museum, becoming Curator of Prints and Manuscripts, then Chief Curator and Archivist, and finally Director. Retired Senior Cataloguer Nora Hague, hired in 1969, succinctly describes Dobell as “clever, strategic and forceful” when taking on the “majority male” McGill administration. Among the employees, Nora recalls, “There was no doubt at all about who was in charge: it was Mrs. Dobell. She had her finger on the pulse of the McCord and was aware of absolutely everything.”

In the late 1950s, with the ageing and crowded McGill Union building due to be replaced by a new university centre on McTavish Street (now known as the William Shatner University Centre), it was suggested that the old Union might make a suitable home for the McCord Museum. Isabel Dobell sensed that the idea of converting the building originally commissioned by Sir William Macdonald for the use of the McCord Museum might appeal to Mr. Stewart. Indeed, he and his wife became generous anonymous benefactors for the major renovations that took place from 1966 to 1968.12 These included an extension of the small 3rd floor mezzanine over most of the area of the former ballroom, the construction of storage areas, and an addition to the rear containing a freight elevator, washrooms and an additional staircase.

The renovations completed, the McCord Museum collections moved into their new home and staff began planning their opening exhibitions in detail. Then came a major setback. In the fall of 1970, McGill announced that the planned opening of the McCord Museum to the public in 1971 would not happen, due to a University-wide lack of funds. A dejected but determined Isabel Dobell contacted the Stewart family once more to ask for enough funding to open one day a week for a year, buying time to solicit more external funding and “give the public a chance to see what the McCord had to offer.”13 Mrs. Walter M. Stewart and her daughter Beatrice Molson generously came to the rescue, enabling the McCord Museum to open as planned.

It is quite fitting that the McCord Museum, enhanced with the Stewart Museum’s extensive collections and a longtime beneficiary of the generosity of members of the Stewart family, will now be known as the McCord Stewart Museum.

NOTES

1. When in the planning stages and under construction, The Montreal Star and The Gazette newspapers tended to refer to it as the “McGill Students’ Union.” By the time of its official opening in 1907, it had been shortened to the “McGill Union,” or sometimes simply the “Union” in McGill University publications.

2. McGill Outlook, March 10, 1903; The Montreal Star, Saturday, February 9, 1907, p. 15.

3. Annual calendar of McGill College and University, 1907-1908, p. 241. According to an article in The Gazette, February 17, 1905, Sir William Macdonald also donated the land and an additional $35,000 to the project. Macdonald was not a McGill graduate, but he was a generous benefactor of the University, donating over $13 million during his lifetime. Stanley Brice Frost and Robert H. Michel, “Sir William Christopher Macdonald,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. XIV (1911-1920).

4. See the McGill University Gazette, Vol. 9, No. 5, December 9, 1885, p. 12, and McGill Fortnightly, February 5, 1896, p. 1.

5. The McGill Daily, Vol. 01, No. 01, October 26, 1911.3.

6. Old McGill yearbook, 1930, p. 204.

7. Isabel Dobell, “Buried Treasure” in Margaret Gillett and Kay Sibbald, eds., A Fair Shake, p. 139.

8. “Buried Treasure,” p. 141.

9. Beatrice’s brother David Macdonald Stewart (1920-1984) was the founder of the Stewart Museum.

10. The Gazette (Montreal), Monday, December 16, 1968, p. 8.

11. “Buried Treasure,” p. 142.

12. After Walter Stewart’s death and just before the reopening of the renovated building in 1971, Mrs. Stewart relented and allowed the inscription of their names on the wall of the entrance hall. “Buried Treasure,” p. 144.

13. “Buried Treasure,” p. 146.