Alexander Henderson, landscape photographer

Although he worked in the style of realism common to his contemporaries, it was a realism intensified by the force of his personal vision.

February 3, 2023

Westerly gales and the heavy seas of a late October storm had buffeted the steamer Baltic for eleven consecutive days on her passage from Liverpool to New York, often with enough force to slow her speed to three nautical miles per hour.1 When the ship docked at half past eight on the morning of Saturday, November 3, 1855, two of the weary travellers who disembarked were Mr. and Mrs. Alexander Henderson, destined for Montreal.2

At that period in his life, the twenty-four-year-old Henderson was an accountant with adventure in his heart and money in his pocket, keen to further his fortunes in the New World. As it turned out, he would become an internationally known photographer whose Canadian landscapes, city scenes and views of outdoor activities received the highest praise at home and abroad.

They were eagerly sought by both Canadians and visitors to this country as records of places or events seen, or simply for the artistry of the images themselves. At least one individual, farsighted Montreal lawyer David Ross McCord, who founded the McCord National Museum (now the McCord Stewart Museum) in 1921, collected them avidly for their historical value.

| Explore Alexander Henderson’s photographs on the Online Collections |

GROWING UP IN THE COUNTRY

Henderson was born on July 9, 1831, to a family of comfortable means and well-established social position. His family owned Press Castle and its large estate, southeast of Edinburgh. Here were woods and hills to explore, craggy mountains to climb and crystal streams in which to test his skills as a fisherman.

Even the death of his father, when Alexander was nine years old, did not disturb this pastoral peace for long, as his uncle Eagle Henderson (1803–1853), who also lived at Press, soon took him under his wing. It was Uncle Eagle who took him on many memorable fishing trips and sent the nineteen-year-old youth to London in 1851 to visit the Great Exhibition, the first ever world exposition. This visit and other trips to England, complemented by the family interest in art, gave the young Henderson a sound cultural grounding before he sailed for the New World.

A NEW LIFE IN CANADA

On October 4, 1855, Alexander Henderson married Agnes Elder Robertson (1828–1895), a daughter of old family friends. Two weeks later, on the 20th, the couple set sail from Liverpool, armed with letters of introduction to influential bankers and politicians in Toronto, Kingston and Montreal.

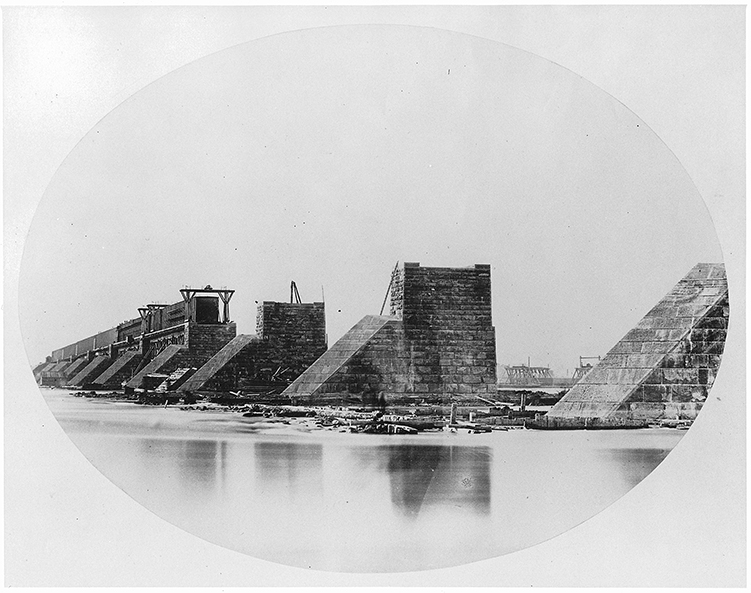

The Hendersons slipped quickly into their new life in Canada. They moved into number 3 Inkerman Terrace, one of a recently completed group of row houses on Drummond Street3. Close to markets, theatres and churches, and only a few blocks from the city’s commercial centre, the district had a special appeal for someone raised on a large country estate. It was surrounded by orchards as well as buildings, and offered a magnificent view of the river, where on a clear day could be seen the tiny figures of men working on the first piers of Victoria Bridge.

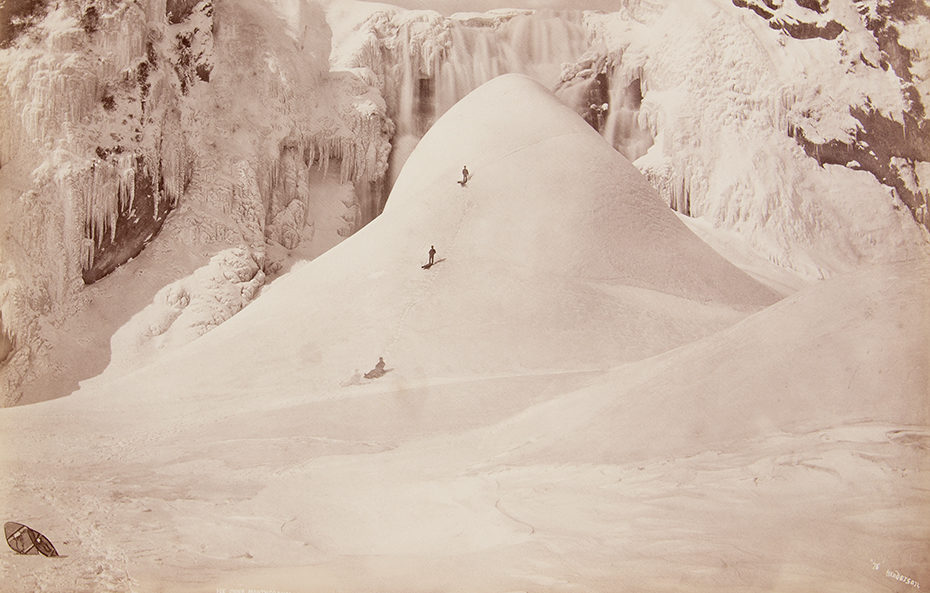

Just as the Hendersons adapted smoothly to their new life in Montreal, the challenge of the Canadian wilderness was no hurdle to the young outdoorsman. During their first winter they spent a lengthy holiday in Quebec City, where they hired a sleigh and joined the throngs travelling over the frozen Saint Lawrence River to Montmorency Falls, there to experience the thrill of tobogganing down the ice cone formed by the freezing spray.

BEGINNINGS IN PHOTOGRAPHY

There is little information available about Henderson’s beginnings in photography, although the pages of early photographic journals do yield some clues. Soon after the London-based journal The Photographic News began publication on September 10, 1858, Henderson became a regular subscriber and contributor. That he took up photography in 1857 can be deduced from a remark he made in a letter published in the October 21, 1859 issue. He wrote: “About two years ago a circumstance occurred to me which astonished me at the time (I was then a beginner) …” This is the only hint we have that he took up photography in Canada, rather than in Scotland.

We also learn from The Photographic News that as a member of the Amateur Photographic Association, formed in 1861, Henderson submitted prints for an exhibition organized by the Association to be held in London in 1863. Although this exhibition never actually took place, he was awarded a third prize and an honourable mention out of a field of between two and three thousand entries.4 One of his winning photographs was a very fine “instantaneous” view of the steamer Mountain Maid on Lake Memphremagog.

In February 1865, at the annual exhibition of the Art Association of Montreal, Henderson displayed fourteen of his photographs. Later in the year, Henderson published his first major collection of photographs in the form of an album. Clearly, here is no struggling beginner, but rather a talented, serious amateur. The publication must have represented a personal milestone for the photographer, likely encouraging him to henceforth devote his life to the art, as a professional.

FROM AMATEUR TO PROFESSIONNAL

On October 8, 1866, Henderson gave up any lingering interest in pursuing an accounting career to open a portrait studio at 10 Phillips Square5. by December 19 he was advertising himself as a “portrait and landscape photographer.”6 Portraiture seems actually to have played only a minor part in the business, since so few portraits by Henderson appear in collections, all of them early works. By the time of the 1874 move to Saint James Street, he was referring to himself as a “landscape photographer.”

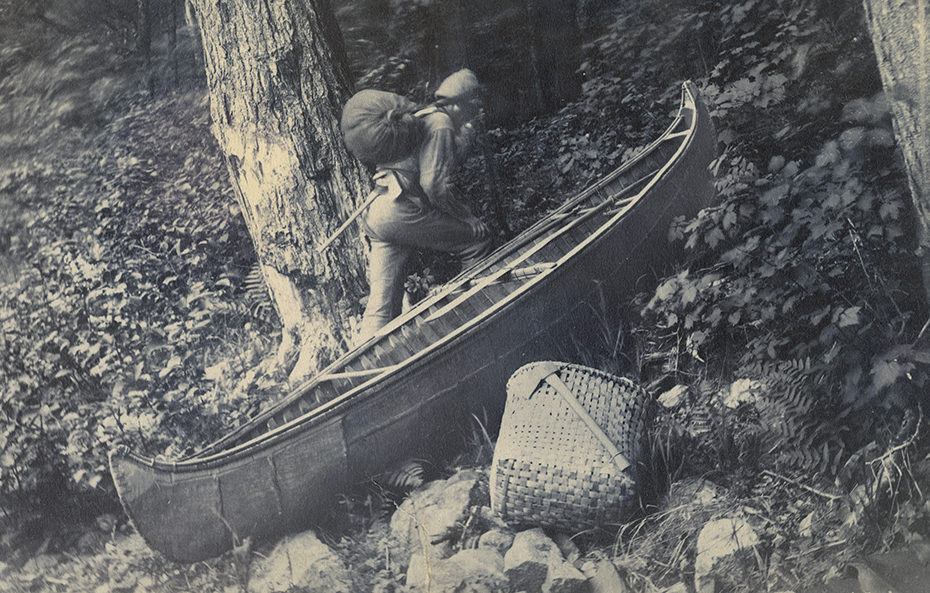

Henderson’s numerous views of the city’s street life, buildings and markets are alive with human activity, and although landscape was his favourite subject, even the works in this genre are usually composed around such human pursuits as tilling the soil, cutting ice on the river or paddling a canoe down a woodland stream. A sufficient market existed for such scenes, and for others depicting the timber trade, steamboats and railways, to enable a skilled photographer to make a living.

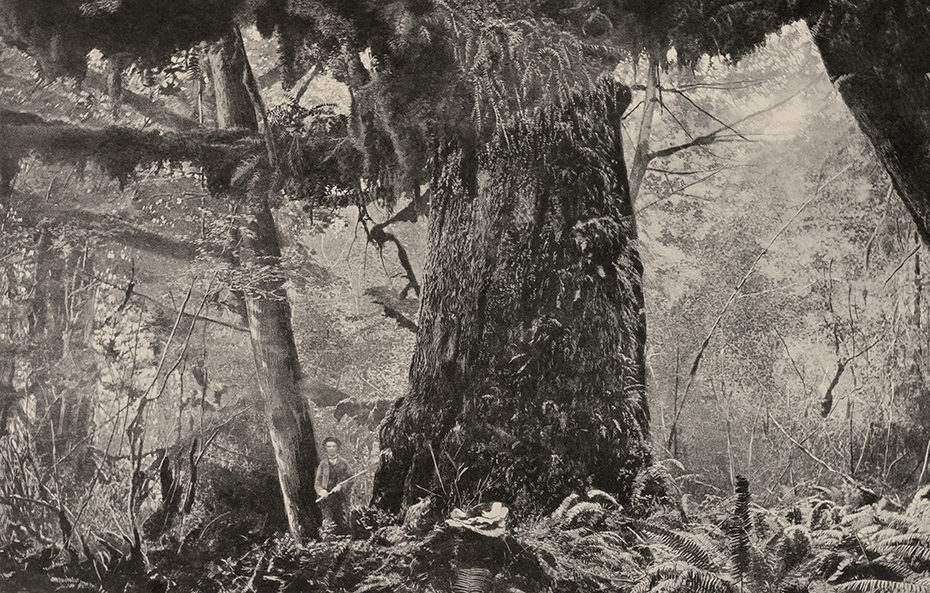

STYLE AND TECHNIQUE

Stylistically, Henderson’s work conforms to the tradition that held sway in the nineteenth century. The camera’s ability to portray minute detail appealed in an age when realism dominated both landscape photography and portraiture. Nevertheless, while his photographs are evocatively realistic, Henderson’s use of light and texture, together with his meticulous composition, carry his work far beyond that of most other contemporary Canadian landscape photographers.

Because photography as an industry was still in its infancy, a nineteenth-century photographer had to effectively blend the skills of artist, businessman and chemist. Successful practitioners of the art were alert to new processes that could make it easier, cheaper or faster to render the desired tonal qualities. Though he shared this interest with his colleagues, Henderson was perhaps more zealous than most in his search for the perfect negative material.7

During his years as an amateur Henderson used to buy his supplies from William Notman and must therefore have been an at least occasional visitor to the popular De Bleury Street studio.

A photograph of Henderson taken by William Notman around 1864–1865 offers further evidence that the two men knew each other well, traded information and may have collaborated on experiments. It is one of three portrait photographs taken in Notman’s studio that were exposed by the light of a magnesium flare. One of the subjects is William Notman, and the other two are Alexander Henderson and Dr. Gilbert Prout Girdwood, a pioneer in radiography in Canada.

MAJOR NATIONAL PROJECTS

In 1872 Henderson began photographing various construction projects on the Intercolonial Railway (ICR). He continued this work intermittently until 1875, when he received a commission from the ICR to photograph all the principal structures along the almost completed line connecting Montreal to Eastern Quebec and the Maritimes.8

Henderson took advantage of the success of the ICR project to generate contracts to photo‐ graph other railway works. In 1877 he and Jules-Ernest Livernois (1851–1933) were commissioned by the Quebec government to photograph all the bridges on the provincially owned Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa and Occidental Railway (QMO&OR).

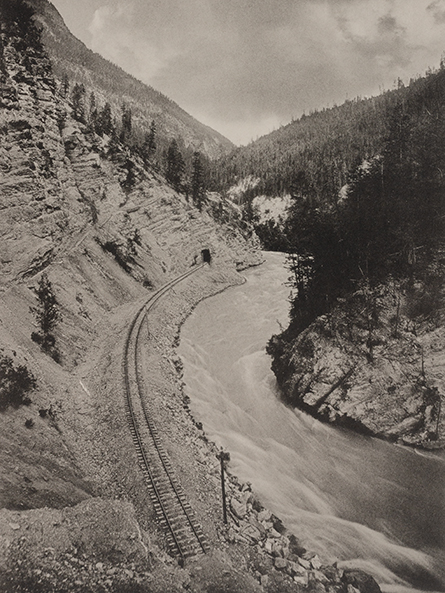

The fact that many of the bridges Henderson photographed were built for the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) may have led to the contract he later received from that company. At their behest, Henderson left Montreal in July 1885 to take photographs in the far West, along the almost completed rail line. The exciting prospect of the trip must have appealed to his adventurous soul, but an unfortunate case of “mountain fever” forced him to return home after only a little more than a month.9

Nevertheless, the CPR authorities must have been well pleased with his work, for in January 1892, when they decided to create their own photography department, Henderson was offered and accepted the position of manager. His duties, which began on April 1 at a salary of $166.67 per month, included photographing in the field.

Later that year, Henderson made his second trip out West. He left Montreal, this time comfortably installed in Photographic Car no. 200. Only eight images from this trip have been positively identified, one in the Provincial Archives of British Columbia and seven in the McCord Stewart Museum’s Photography Collection.

FINAL YEARS

From the few references to Henderson and the photography department in the CPR Archives, it is impossible to reconstruct a full story of his years with the railway. The 1897 Lovell directory describes him simply as “artist,” from which it may be assumed that he had again left the CPR. The lack of any occupational designation in the directories of following years likely reflects his retirement late in 1897.

After Henderson’s death in Montreal on April 4, 1913, his residence at 631 Belmont Avenue, in Westmount, remained in the family. It was from its basement, near the end of 1965, that his grandson Thomas Greenshields Henderson (1906–1969), who had inherited the house, removed the precious glass negatives and disposed of his grandfather’s life’s work by way of the municipal garbage service. It seems that the family had put photography out of their minds, as there is not a single mention of Henderson’s photographic activities in any of the obituaries published on his death in 1913.

The value of Henderson’s photographs – in social and historical research, in education and, generally, in bringing the past to people – is inestimable. How lucky we are to have had the sensitive mind of Alexander Henderson to document four decades of the nineteenth century for further generations!

Although he worked in the style of realism common to his contemporaries, it was a realism intensified by the force of his personal vision. He knew the value of light and used it boldly to evoke depth and mood, creating photographs that were no mere factual records but rather moving documents of the land.

___

The full version of this essay was published in Alexander Henderson – Art and Nature, edited by Hélène Samson and Suzanne Sauvage.

NOTES

1. ‟Arrival of the Baltic,” New-York Daily Times, vol. 5, no. 1289, November 5, 1855, p. 1.

2. ‟List of Passengers by the Baltic,” The Gazette (Montreal), vol. 70, no. 264, November 7, 1855, p. 3.

3. MacKay’s Montreal Directory, 1856, p. 126.

4. The Photographic News (London), vol. 7, no. 255, July 24, 1863, p. 356.

5. The Montreal Daily Witness, October 3, 1866; The Gazette (Montreal), vol. 92, no. 234, October 1, 1866, p. 2.

6. The Gazette (Montreal), vol. 92, no. 302, December 19, 1866, p. 2.

7. Letter from Alexander Henderson to the editor, ‟Notes on dry processes,” The Photographic News (London), vol. 3, no. 59, October 21, 1859, pp. 82-83.

8. Letter from Sandford Fleming to Ralph Jones, Ottawa, May 25, 1875, Department of Public Works fonds, R182 (Mikan 191397), Library and Archives Canada. See also Alexander Henderson’s ICR views of bridges, tracks, cuttings, tunnels, etc., Sandford Fleming Collection, R7666, Library and Archives Canada.

9. “Mountain fever” is a disease carried by the wood tick, common to the dry mountainous regions of British Columbia and Alberta.