Reimagining Duncan with Iregular

A conversation with Iregular, the digital art studio that used artificial intelligence to reimagine the pictorial universe of James Duncan.

October 11, 2023

Atop the 5-story building that hosts the offices of Iregular, the digital art studio behind Mental Maps, the installation that stands as the vibrant epilogue to Becoming Montreal: The 1800s Painted by Duncan, a terrace overlooks the meeting point of Mile End, Outremont, Little Italy and Parc-Ex. Soft brushstrokes of light grey cover the sky, concealing the sunlight and depicting the otherwise busy crossing of Avenue du Parc and Van Horne as peaceful, and unassuming.

A few metres away, under the same diffused light, which rushes through the same clouds and through the wide windows of the photo studio where I meet the creative team behind the piece, we delight in conversation and try to capture a more figurative portrait of their reimagination of classical art through the eyes of tomorrow.

| Take a trip back in time and visit the exhibition Becoming Montreal: The 1800s Painted by Duncan |

To enlighten readers who may not have experienced Mental Maps yet, how would you explain the project?

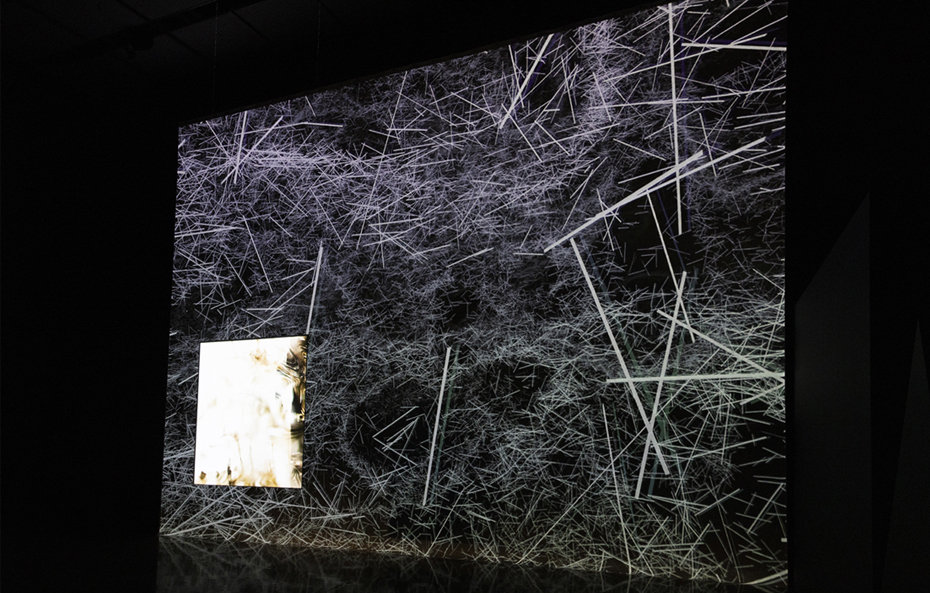

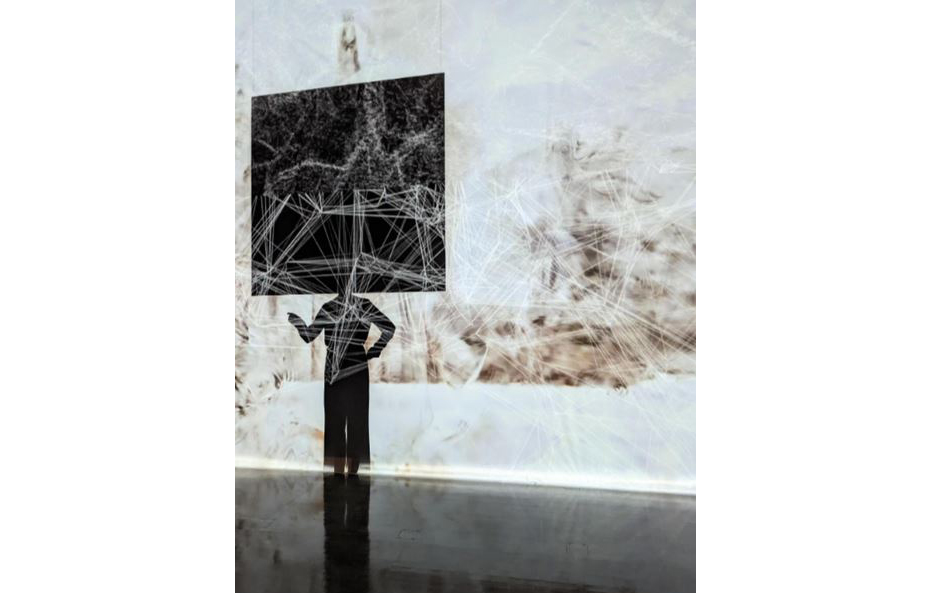

Alice: Mental Maps is an immersive installation that recreates a landscape, using an algorithm, based on what James Duncan painted in the 1800s. It’s composed of two projections: one with a 3D version of the landscape paintings, and another with their graphical interpretation. As you move around the space, your shadow blocks the projection to reveal other hidden layers.

Was the installation designed for public participation?

Daniel: We wanted people to experience our piece from their own point of view. We initially tried for something focussed mainly on how you could influence what you saw, depending on where you were standing. That was sort of the first idea we presented to the Museum. It later evolved to include artificial intelligence that influenced the experience wherever you stood.

What was it like to work with the McCord Stewart Museum?

Daniel: The museum briefed us, and then we started working with Catherine K. Laflamme (the exhibition’s Project Manager), and Stéphanie Poisson (Head of Digital Outreach, Collections and Exhibitions). They trusted us and gave us complete freedom. It was very important that our piece conveyed the vision of the exhibition, so it was very interesting to be able to consult.

Alice: We would meet every week. They came here [to the studio] to experience every prototype.

Was there an evolution from the first draft, or did it remain unchanged throughout the whole process?

Alice: At the start, we thought about using lenticular paper, which has a 3D-effect that lets you see something different from each side. We went through the prototype process with this idea, but found limitations in scale.

Xavier: When Alice told me about the project, I said, Okay, I’ll just get there in the morning and we’ll be done by noon. [Everyone laughs.] And then we ended up going for weeks. I thought that we could map it and be done, but every week we would place the projector and see that we had to move it just a little, and then remap it again, and then move it a little, and then remap it again…

Dana: We did a lot of research to find the right tools, the right techniques. Using the tools, we then found that they could not only do this, but also that. Prototyping helped us a lot.

How did you select the pieces from James Duncan’s body of work? I mean, he was very prolific.

Dana: We used as much as we possibly could. We tried to edit almost geographically; the different locations were basically our themes. There’s the point of view from St. Helen’s Island, and from Mount Royal.

| Explore James Duncan’s works on the Online Collections |

What tools and processes did you end up using?

Dana: The main tool was this software that works with Neural Radiance Fields, which is a machine learning technology. It’s mostly used for photography because you take multiple photos of the same object, from different angles, then you feed it to the software, and it recreates the object in 3D. We decided to do that with scans of the paintings. We situated them in a virtual map of Montreal where they were originally painted, and the software then recreated a virtual environment.

One of the elements that I personally appreciated the most was colour: the ochres and reds appeared very true to the oil paintings. How do you translate solid pigment into something as ethereal as light?

Alice: Each light pixel that you see in Mental Maps is connected directly to the original brushstroke. The program that we created and used allowed us to move around the painting.

What do you mean when you say, “move around the painting”?

Dana: There’s a three-dimensional, virtual space created and filled with pixels coming from the scans of the paintings. That’s why the colours are so similar. It’s the colour from the painting, but in a 3D world. Then, we just take a virtual camera, and we move through this virtual universe.

What about all the techniques Duncan used: watercolor, oil, and ink wash, amongst others. Did the AI have difficulties processing any in particular?

Dana: Black lines on white paper were harder to process because there’s so little information. We can understand it, but the AI doesn’t really. Those were the pieces that needed more finessing.

There’s a heated debate around generative AI and art production. You obviously work with these technologies, but what are your thoughts on the debate?

Dana: We purposefully chose not to use any generative AI in this project because of how messy the technology is right now, but I believe that in the future it will be more regulated and more ethical so that artists can choose whether to use it or not.

Daniel: I can imagine having this same conversation, two hundred years ago, with James Duncan about photography killing his craft.

Celia: As part of a design studio, we need to get involved with these technologies. They’re a great tool for research, for example.

Talking about humans interacting with technology, we are living in an age of digital overload. We go from screen to screen and, soon enough, from goggles to goggles. What does ‘immersive’ even mean today?

Daniel: At the studio, we create immersive experiences that bring people together in a space where they end up having a human experience with other humans who are behaving humanly. For us, it’s more of an interactive, connective experience.

James Duncan was an immigrant, and his eyes and imagination helped create many of the mental images about Montreal, both as a city and as a myth. What do you think the foreign perspective brings to the creation of a city?

Alice: When someone from abroad arrives in a city, a whole new version of that city is born; there are multiple cities within one. There’s not just one truth.

My last question is very simple. What's your favourite spot in Montreal to watch the sunset?

Daniel: The terrace at this studio is epic. We’re so lucky.

Alice: That really is the spot. [Everyone agrees.]