Europeans and the use of wampum belts

See how Europeans adopted the practices associated with exchanging and keeping wampum, contributing to the transformation of these objects.

October 11, 2023

Made from seashells found on the Atlantic Coast, white and purple wampum beads were key trading items in the fur trade, which expanded rapidly in the early 17th century in eastern North America. The beads were also used as currency in Dutch and British colonies until the 1660s.

Iroquoian peoples from inland areas used wampum in their diplomatic dealings with neighbouring nations. The beads were woven into strings and belts of various sizes, containing anywhere from several hundred to over ten thousand beads. These objects were then presented at diplomatic meetings to support what was said, rendering it legitimate and official.

| Explore the wampum preserved at the McCord Stewart Museum on the Online Collections platform! |

Since wampum were used to record spoken words and seal alliances, some were kept for many years to ensure that the messages they conveyed were passed on. To this end, the wampum keeper would periodically repeat their meanings in front of the community so that its members would learn and remember the terms of agreements reached and mutual commitments.

Adoption

In the 17th century, the practice of exchanging diplomatic wampum belts was so well established in eastern North America that Europeans were very familiar with the uses of these objects and recognized their utility and relevance in validating specific interpretations of past events:

[Indigenous peoples] can remember things from so long ago that, when our Governors, or their representatives, meet with them concerning matters of War, Peace or Commerce & suggest things contrary to what was proposed thirty or forty years earlier, they respond that the French go back on their word, that they are always changing their minds, that so many years ago they had told them this & that; & to substantiate their response they bring along the Wampum Belts that we had given them at that time.1

In their numerous and constant diplomatic dealings with their Indigenous allies, the French and British also made extensive use of wampum in a variety of situations: to back up what they said, to extend an invitation, to confirm the terms of an agreement, or to recall mutual commitments. On July 13, 1743, for example, when Governor Beauharnois received a wampum belt from the Shawnee, he responded as follows:

I will take care of this and pass it on to my successors so that you will always be able to claim the bounties of your father. […] I give you this belt; keep it in your villages so all of your descendants may know that it is the knot that binds you to me.2

The many wampum belts the French received were kept in the “King’s Stores” in Quebec City or Montreal. These warehouses also preserved wampum beads, most of which were purchased from merchants who sold them by the thousands. In fact, the lists of goods stocked in these stores record tens of thousands of wampum beads, inventoried by colour—white or “black”—and monetary value.

Though this material quickly became very expensive for colonial authorities, it nonetheless remained essential to maintaining the extensive diplomatic network that New France relied on: without alliances with the Indigenous peoples living on the land, the French colonial presence would have been very tenuous. Since they were located far from the Atlantic shores where the raw material for wampum beads was found, some people tried to make the beads out of other materials like ivory or marble. Obviously, no one was fooled into accepting imitation beads!

Adaptation

When the Indigenous world of oral tradition encountered that of the written word, changes occurred in the way of dealing with these diplomatic objects at the confluence of various cultures.

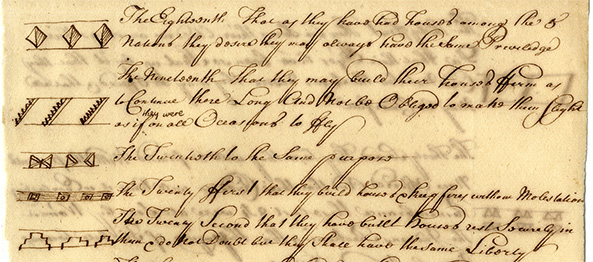

A look at colonial correspondence reveals that the Europeans adapted Indigenous traditions, notably by incorporating the use of the written word. They ensured that every word spoken by their Indigenous counterparts was not only transcribed in real time into a registry, but that these remarks were also numbered so they could be associated with the wampum belt received on the same occasion. The wampum belt itself was labelled so it could be easily found and, more importantly, linked to its initial message. In addition, to help identify and avoid losing track of the objects exchanged and their meanings, the Europeans often took notes describing or sometimes drew pictures of the wampum belts that were passed around at council meetings.

Transformation

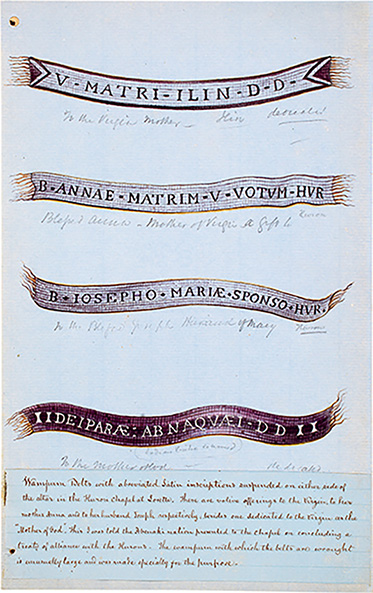

Although the Europeans somewhat modified the practices associated with the exchange and management of wampum belts, they also transformed the object itself by incorporating numbers and letters. The first to do so were the Jesuits. Between 1654 and 1716, they helped produce a dozen or so wampum belts with Latin script. For their part, the British initialled and dated the wampum belts they presented to identify their provenance and the time of the exchange. For example, Sir William Johnson, superintendent of Indian Affairs in eastern North America, gave his Indigenous allies a belt with his initials, “W. J.,” and the date, 1756, while his successor, Guy Johnson, presented several wampum belts with the letters “G. J.” in 1780.3

The practice of writing down what was said sometimes bothered Indigenous leaders, who felt that the written word could significantly diminish the terms of a relationship. Steeped in oral tradition, they considered every negotiated agreement a vital, living thing that had to be periodically renewed. Creating a written form of an agreement made it autonomous, enabling it to be reused at a later date in the absence of representatives and spokespersons. At other times, however, Indigenous people themselves demanded that their words be transcribed and, in some situations, they also preserved handwritten copies of their transactions with Europeans.

Since diplomacy is a process of intercultural connection and understanding, each party must adapt to their counterpart to better communicate. While Europeans adapted the traditions of Indigenous peoples, the latter also adopted certain European procedures, appropriating cultural elements of the other to position themselves at the same level politically.

To learn more

Beaulieu, Alain and Réal Ouellet. Lahontan : Œuvres complètes, vol. I. Montreal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 1990 (1702).

Becker, Marshall Joseph and Jonathan Lainey. “Wampum Belts with Initials and/or Dates as Design Elements: A Preliminary Review of One Subcategory of Political Belts.” American Indian Culture and Research Journal, vol. 28, no. 2, 2004, pp. 25-45.

Library and Archives Canada, MG1-C11A, Archives of colonies, general correspondence, Canada.

Lainey, Jonathan. La « monnaie des Sauvages ». Les colliers de wampum d’hier à aujourd’hui. Quebec City: Septentrion, 2004.

Lainey, Jonathan. “Les colliers de porcelaine de l’époque coloniale à aujourd’hui.” Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, vol. 35, no. 2, 2005, pp. 61-73.

Notes

- Lahontan, Œuvres complètes, vol. I, pp. 649-650.

- Response of Beauharnois to the words of the Shawnee, July 13, 1743, Library and Archives Canada, MG1-C11A, vol. 79, fol. 102.

- Lainey, 2004 : 71-80; Becker et Lainey, 2004; Lainey, 2005 : 64-65.