Griffintown – Evolving Montreal

History at your fingertips! The Urban Tours provide a fun way to learn more about the history of certain Montreal sites.

June 18, 2024

Take an exclusive outdoor tour thanks to historical images from the Museum’s collections.

Using your phone, explore the various tours and discover the history of many city sites and images that bear witness to the Montreal of the past.

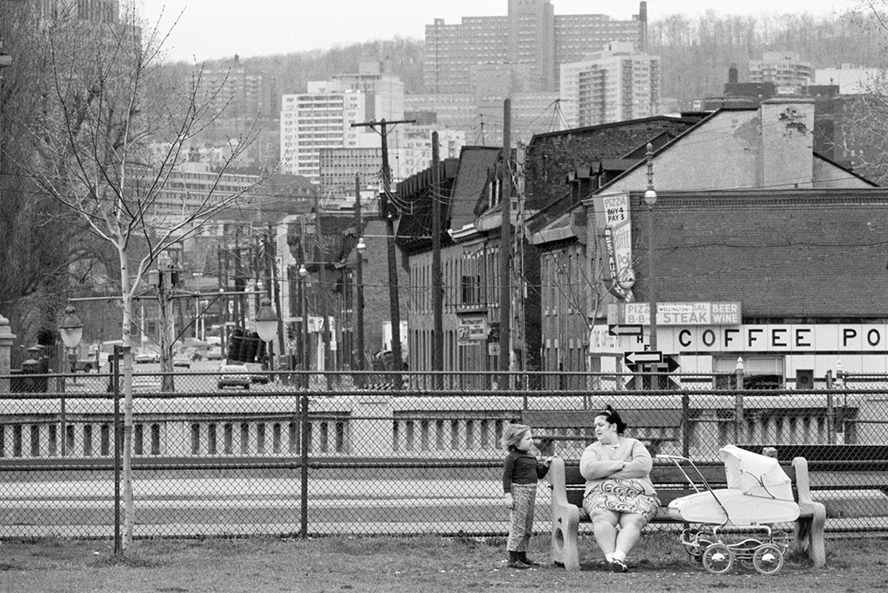

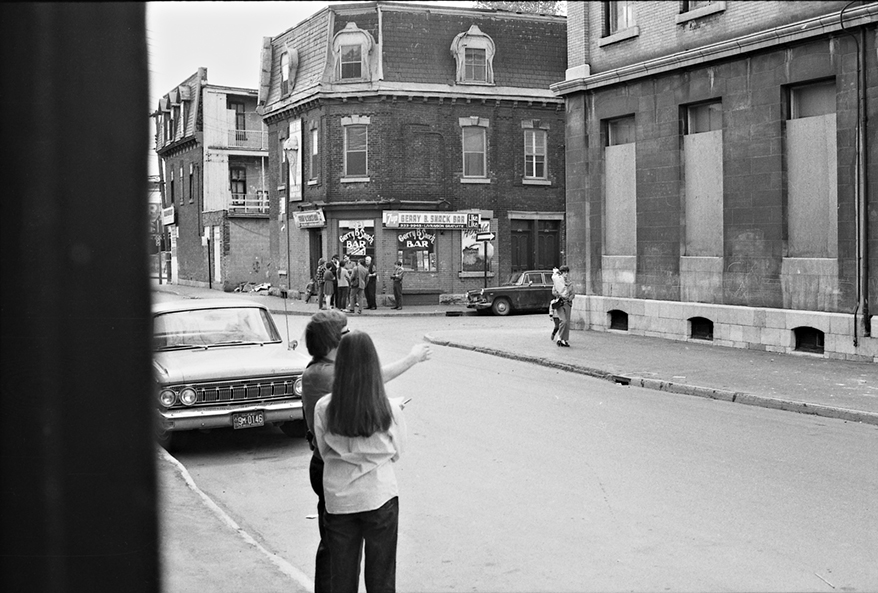

Over the past ten years, extensive structural and architectural transformation has made visible evidence of Griffintown’s industrial, working-class roots increasingly hard to find. But these recent changes represent only the latest chapter in a cyclical history of destruction and renewal.

The McCord Stewart Museum invites you to take a walk to discover some of the many changes that have transformed this mythical district since the 18th century.

1. HAYMARKET SQUARE AND ST. STEPHEN’S CHURCH

The building pictured on the left is St. Stephen’s Church (demolished 1950), and St. Mark’s Presbyterian Church (demolished 1920s?) can be seen in the distance, across the square.

Griffintown is situated on low-lying ground, and during the 19th and early 20th centuries spring flooding was not unusual. When the water was particularly high, as seen in the photograph, people got around on anything they could find that would float.

When not flooded, the square functioned as a market for hay, an important commodity given the thousands of horses living in the city at that time. This bird’s-eye view of the square shows St. Stephen’s Church and, to the right of it, wagons of hay surrounding the weigh station building, with its octagonal roof.

The Canadian National Railways viaduct divided the square in the 1930s, and later construction of the Bonaventure Expressway rendered the east side inaccessible. The recent opening of Bonaventure Park has transformed a portion of Haymarket Square once again into a public space.

Construction of the massive expressway had a major impact both on access to Griffintown and its visual landscape. It is easy to imagine the reactions sparked by the project among the local population.

2. GAULT BROTHERS BUILDING

This factory, which manufactured shirts, ties and ladies’ blouses and undergarments, was constructed in 1901 for the Gault Brothers’ Company Limited. Gault Brothers were also importers of woollen material and dealers in Canadian woollens and cottons.

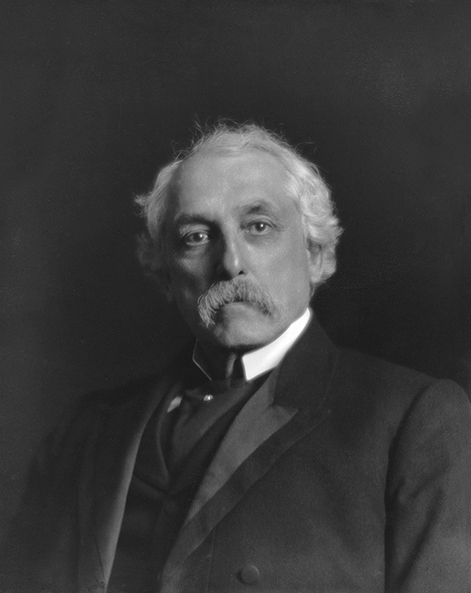

Andrew Frederick Gault, the Irish-born founder and president of the firm, was also the head of a number of manufacturing companies. As the result of his determination to organize the cotton textile industry he became known as the “Cotton King of Canada.”

Just around the corner, on William Street, the Walter M. Lowney Company of Canada – manufacturers of cocoa, chocolate and “chocolate bonbons” – built a large factory and warehouse in 1905. Their flourishing business took over the Gault building during the 1920s. After Lowney moved its operations to Sherbrooke in 1960, leather goods were produced in the building through to about 1992. Today, it forms part of a condominium complex known as The Lowney.

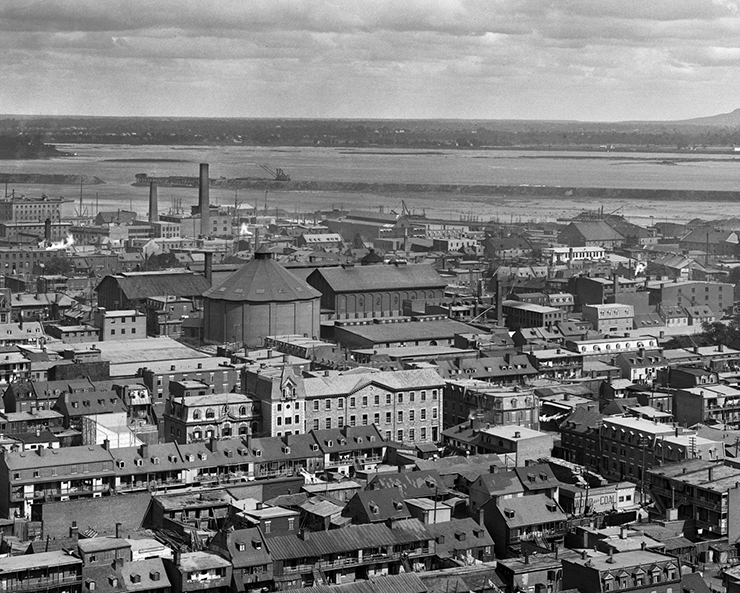

3. NEW CITY GAS

When the New City Gas Company was incorporated in 1847, the goal of its directors was to provide lighting for public squares, streets, shops and private dwellings. They planned to offer gas “in greater quantity, of better quality, and at a cheaper rate” than their competitor, who had previously held the monopoly. Gas lighting also had an important impact on industry at the time, since it allowed factories to continue operating after nightfall.

Gas was produced here by heating coal and separating the combustible gases from the solid material. The coal gas was distributed to customers through underground pipes.

The brick exterior of the building you see in front of you is from 1861, but the two-storey stone façade on its east side probably dates back to the founding of the company. The brick building slightly behind and on your right, visible in the 1896 photograph, was a second facility added between 1859 and 1861.

Originally, the building and its installations made it possible for industries to extend their hours of production by working day and night.

Today, New City Gas has been reborn as a premier live music venue and a hotspot of Montreal nightlife.

4. GRIFFINTOWN CLUB

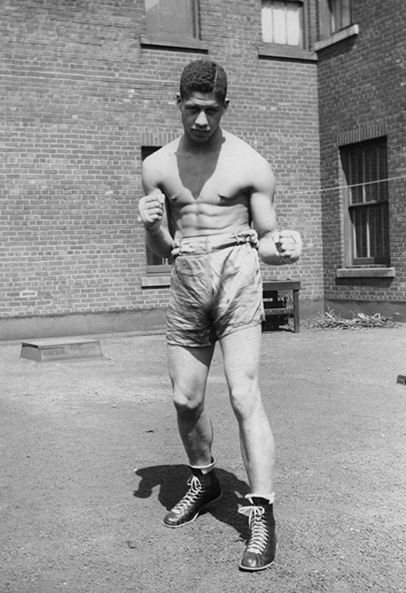

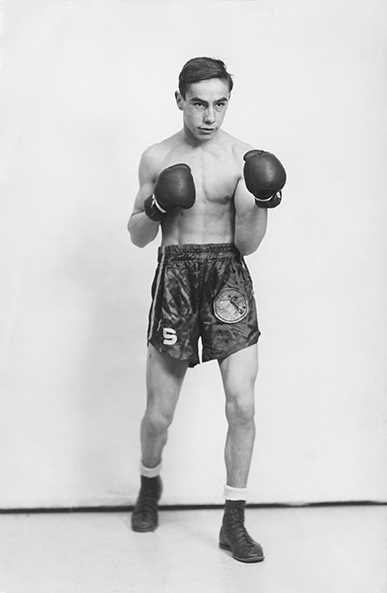

From 1930 to 1953 the Griffintown Club was located here at the corner of Ottawa and Shannon streets. The goal of the Club, founded in 1908 by Owen Dawson, clerk of the Juvenile Court, was to offer sports and other activities to the local boys, to keep them productively occupied and discourage “mischief” in the streets. A girls’ section was soon added.

From quite early on, boxing was a popular sport among boys at the Club. Cliff Sowery, the Griffintown Club’s director of physical activities, seen in this group portrait along with coach Richard “Dutchy” Pierson, trained a number of champion boxers.

Club member Jimmy Davies won the light-heavyweight titles in the Provincial and the Dominion Boxing Championships of 1946. Armand Savoie competed in the 1948 Olympics and later became a successful professional boxer.

The Griffintown Club was a social hub for the local community, offering activities for boys and girls from preschool age through to young adulthood. Social and educational activities were also available to their mothers.

The Club’s small staff and team of volunteers rallied to help out as best they could when, on the morning of April 25, 1944, a Liberator bomber crashed nearby, only minutes after taking off from Dorval. Two three-storey tenements on Shannon Street, not far behind where you are standing now, were destroyed, and a third fronting on Ottawa Street was heavily damaged. The five crew members aboard the bomber were killed, as were ten residents from the neighbourhood.

During the first half of the 20th century, Griffintown still had a community life. Today, there are few community organizations operating within its boundaries, despite the recent increase in activities and population. But several local initiatives are under way, and there are plans to open a primary school. Will this provide the social fabric with the impetus it needs to develop?

5. DOW BREWERY

Although no beer is made here now, a brewery was operating here as of 1808, when brewer Thomas Dunn moved to Montreal from Laprairie. In 1818 or 1819 Dunn hired William Dow, a young Scottish immigrant with experience in brewing, as a foreman.

By 1829 Dow had become a partner in the firm, and after Thomas Dunn died in 1834 the brewery’s name was changed to William Dow & Company.

By 1829 Dow had become a partner in the firm, and after Thomas Dunn died in 1834 the brewery’s name was changed to William Dow & Company. By 1863, not long before he sold the company and retired from brewing, Dow was making about 700,000 gallons of beer annually, as compared to the 142,000 gallons produced by Molson’s Brewery.

In 1909 the Dow brewery amalgamated with Dawes, Ekers and Union to form National Breweries Limited. Beer was still produced under the Dow name until the 1990s.

This building, which combined a brewing facility and a warehouse, was constructed between 1924 and 1925.

6. MONTREAL WAREHOUSING COMPANY

The Montreal Warehousing Company began operations in 1869, with Montreal shipping magnate Hugh Allan as president. Thomas Cramp, also in the shipping industry, was vice president.

The company’s main warehouse, was situated in a strategic location. The Grand Trunk Railway tracks, connecting with Portland, Maine, ran along the front of the building on what is now Smith Street. To the rear was the Lachine Canal’s flour basin (now Peel basin), where steamers arriving from the Great Lakes and larger ocean-going steamships could dock.

An 1886 publication explains that the building, seven storeys high at the west end and five at the east, had the capacity to store 400,000 bushels of grain and 80,000 barrels of flour. Four steam-operated “elevators and descenders” were located at the centre of the building to facilitate loading and unloading.

The building was demolished in 1931, and the site is now occupied by the Canadian National Railway tracks leading to Central Station.

7. GALLERY SQUARE

Gallery Square and its bath building were named for Alderman Daniel Gallery, an Irish-born merchant tailor and resident of Griffintown.

Daniel Gallery represented St. Ann’s Ward on the Montreal City Council and was also an elected Member of Parliament.

In July 1899 he recommended the construction of a public bath near the Wellington Bridge. It was a necessity, he explained, in this crowded and overheated part of the city, where “the children are in the canal there like ducks in the water and have been frequently arrested.”

Opened in 1901, the Gallery Bath housed a swimming pool and showers for the use of residents of buildings without hot water.

Thirty years later, the construction of the Wellington Tunnel under the Lachine Canal, which drastically reduced Gallery Square in size, would also require demolition of the bath. The building still standing in the square today is the “comfort station” – public urinal – that replaced the Gallery Bath in 1932.

In the early 20th century public bathhouses were urban facilities essential to the well-being and health of working-class communities like Griffintown. Today, what public facilities are considered necessary to a neighbourhood to ensure its residents’ quality of life? What examples are there in your own neighbourhood of public services that enhance people’s lives?

8. ST. ANN’S CHURCH

Irish immigrants settled in large numbers in Griffintown, many of them arriving between 1845 and 1849 during the potato famine. Work was readily available to them in nearby industries and factories along the Lachine Canal.

St. Ann’s mission was founded in 1848 to serve a growing population of English-speaking Roman Catholics of mostly Irish descent. St. Ann’s Church soon followed, opening in 1854.

A century later, in 1951, a newspaper article reported that St. Ann’s church was still at the centre of the Irish community’s “religious, social and business life,” reflecting its “very heart and soul.”

Even so, the Irish community was diminishing as the local population pursued job opportunities elsewhere. By the end of the 1960s St. Ann’s Church, which had once boasted a congregation of some 1,200 families, was serving only about 90. The last services were held on February 1, 1970, and the church was demolished later that year.

This space has great significance for the neighbourhood and its residents. As it appears today, how does the space help to evoke and contextualize the history of Griffintown?

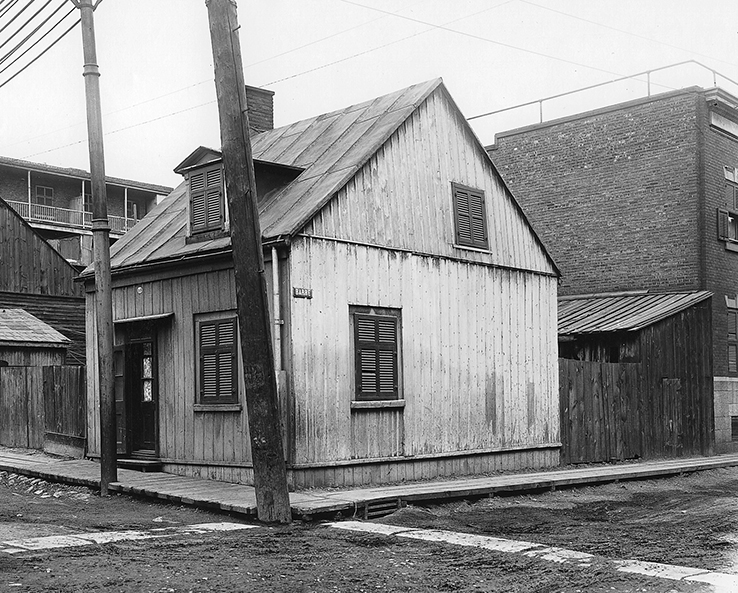

9. KEEGAN HOUSE

Between about 1863 and 1891 this building was the home of Irish-born schoolteacher Andrew Keegan, his wife Ellen and their family of eight children.

It is quite likely the oldest house in Griffintown. According to urban heritage expert David Hanna, the shape of the roof, the wood mouldings, and the finish and arrangement of the bricks dates the building to between 1825 and 1835.

Hanna believes that Andrew Keegan may have acquired the house from the City of Montreal when Smith Street (now Wellington) was being extended through to McCord Street (now De la Montagne). If this is the case, the house has been moved twice in its nearly two centuries of existence: once by Keegan, who moved it here from Murray Street, and a second time in 2015, when it was temporarily displaced to protect it during construction of the Brickfields condominium project.

The preservation of this architectural witness of Montreal’s past represents a victory for heritage protection. The restored house has been integrated into a modern condo project, serving as the complex’s lobby.

Does this kind of fusion of historical and contemporary buildings appeal to you? How well do you think it works here?

10. HORSE PALACE

Leo Leonard, also known by the nickname of “Clawhammer Jack,” was the owner of the “Horse Palace,” located on Ottawa Street between Eleanor and Murray. Dating back to the 1860s, the stable was home to some of the calèche horses that took tourists through the streets of Old Montreal.

When Leo Leonard retired in 2011 controversy erupted over the fate of the stable, located in an area undergoing rapid development.

Montreal’s horse-drawn carriages, or calèches, disappeared for good in 2019, victims of the City’s decision – after several years of debate – to ban the activity from its streets. Issues related to animal health and welfare finally won out over the heritage value of the stable and of what it symbolized, and the fate of those working in the trade.

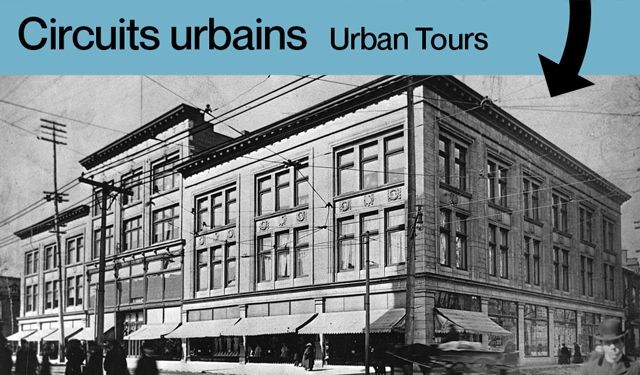

11. MONTREAL STREET RAILWAY POWER HOUSE

This photograph, taken in 1894, looks across William Street to the newly constructed street railway powerhouse. This plant burned coal in order to operate steam-driven electrical generators, which in turn powered the overhead lines supplying Montreal’s electric streetcars.

There had been public transportation in Montreal in the form of horse-drawn trams since 1861, but in 1892 the Montreal Street Railway introduced electric streetcars to the city. Service was limited at first, but as the system grew, so did the company’s need for power.

Three years after this photograph was taken, the company added another boiler house and a “mammoth” chimney rising over 255 feet in height, said to be the tallest in Canada.

Hydro-electricity from water-driven plants eventually replaced coal as the main source of power for the city’s streetcars, and by 1922 the William Street steam power plant was used only rarely, as emergency back-up for the system.

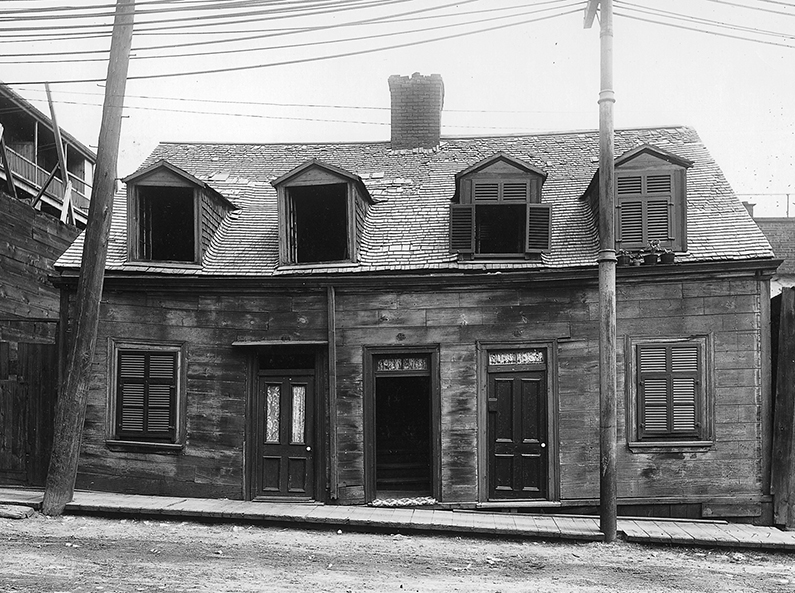

12. BARRÉ STREET HOUSE

According to the 1901 census, John Caldwell, an Irish-born labourer, lived with his wife Mary in the house pictured here, which was at 149 De l’Aqueduc Street.

The fate of the building was the same as that of many small homes in growing working-class neighbourhoods like Griffintown at the beginning of the 20th century. Demand for housing was high in Montreal, which nearly tripled in population between 1890 and 1920. Land had increased in value, and single-family houses were gradually being replaced by new styles of dwelling – the duplex and the triplex.

In the 1910 city directory, 149 De l’Aqueduc Street is listed as vacant. By the next year, a number of new addresses appear in its place. It seems that construction of a triplex was under way, and by 1914 occupants are listed for each of the twelve housing units in the new building on this corner.

A number of older buildings in the area were photographed by the Wm. Notman & Son studio in 1903. The photographs were ordered by a Mr. Meredith, who may have been a real estate developer or a bank manager.

Today, Griffintown is a particularly densely populated residential sector of Montreal. The single-family homes of its early days were replaced by duplexes and triplexes, and these have in turn given way to apartment blocks with hundreds of residents.

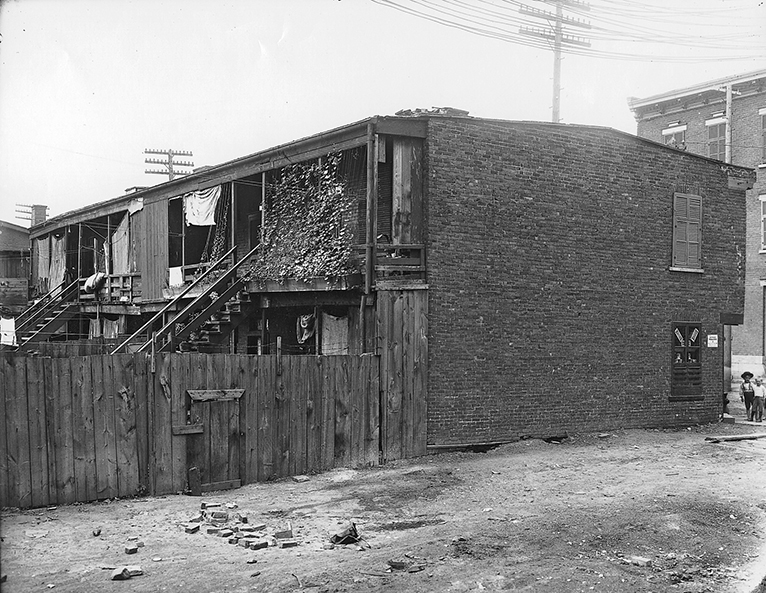

13. JOSEPH BASTIEN’S GROCERY STORE

This two-storey brick building once situated on Barré Street, at the corner of Gareau Lane, is typical of the first row houses built in Montreal around 1860.

Unlike the later style of buildings in Montreal, which were set back from the street and had outdoor staircases, this series of row houses was built right on the edge of the lot, and the stairs to the second-floor dwellings were indoors.

When these photographs were taken in 1903, the corner entrance on the left led to Joseph Bastien’s grocery store at 142 Barré. Joseph lived two doors over, at 146 Barré. Longtime resident Catherine Gareau, a widow, lived at 144. It’s possible that her late husband Joseph Gareau, a mason, constructed this set of row houses in the early 1860s.

14. MCCORD STREET

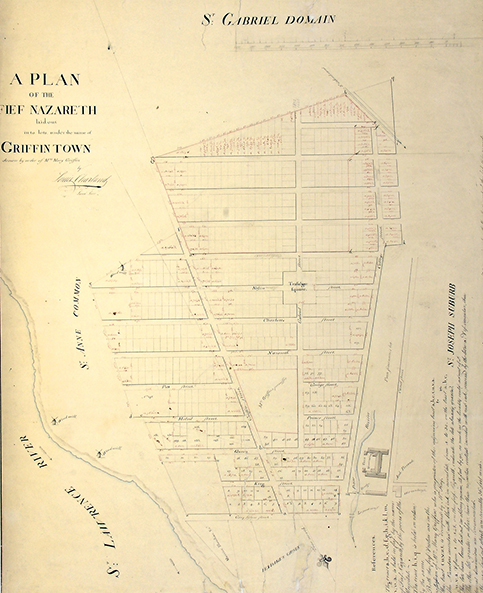

You are now standing on the section of De la Montagne Street formerly known as McCord Street, which ran from here on Notre-Dame, south to Wellington Street and the Lachine Canal. It was named for Thomas McCord, who emigrated from Ireland to Quebec with his family as a child, in about 1760.

In 1792 and 1793, McCord acquired 99-year leases on two properties in this area, known as the fief of Nazareth and the Sainte-Anne concession. Between 1796 and 1805 McCord was living in Ireland, having left his business affairs in the hands of his nephew by marriage.

Through a series of manipulations, unknown to McCord at the time, the nephew sold the land to Mary Griffin, who divided it up into lots for sale. McCord sued, and by 1814 the leased land had been returned. The area, however, remained commonly known as Griffintown.

It was Thomas McCord’s grandson, David Ross McCord, who founded the McCord Museum.