Robert L. Ridley, Northern Photographer

Step aboard the S.S. Thetis and discover the Canadian Arctic through the lens of early 20th-century traveller Robert L. Ridley

August 2, 2024

Historical Context and Cultural Sensitivity

Some archival documents may include texts that could be considered offensive, particularly with regard to the language employed to refer to racialized, ethnic and cultural groups. The language used by the creators of these documents does not represent the values promoted by the Museum.

Setting sail for the Arctic

It’s early in the morning of July 18, 1920, when the S.S. Thetis steams off from Montreal. Originally a whaling vessel built in 1881, the Thetis has been hired out from its current owners, Newfoundland’s Job Brothers, for a two-month mission to establish fur trading posts in Hudson Bay. It’s a turbulent time for the Arctic fur trade, and the new Lamson and Hubbard Canadian Company (LHCC) plans to go head-to-head with the 250-year-old Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC).

On board is Robert L. Ridley, a former HBC fur trader now employed by Lamson and Hubbard. He is responsible for ensuring the new trading posts are built and equipped with enough fuel, supplies and trade goods to last until “ship time” the following year. With camera and pen in hand, Ridley – or RLR as he fashioned himself – created a captivating portrait of his northern journey.

RLR’s photo collection and the Thetis album

Robert Ridley’s photograph collection at the McCord Stewart Museum, available on the Museum’s website, consists of two photo albums and more than 500 loose photographs (many of which also appear in the photo albums).

| Discover Robert Ridley’s photographs and travel diary on Online Collections |

Taken together, these images capture the places and people Ridley encountered during his travels throughout northern Canada from 1913 to 1920, forming part of the extensive visual record of the Canadian North that can be found in museums and archives across the country. This examination of the Ridley collection will focus on the album devoted to his 1920 voyage on the Thetis. Composed of a selection of 56 images from the 162 photographs Ridley took during this trip, the album is arranged chronologically, with several photos per page and accompanying descriptive captions that in some cases provide identifications of people and places, together with other contextual information.* This album, along with Ridley’s journal and associated correspondence, provides fascinating insights into the tradition of northern photography.

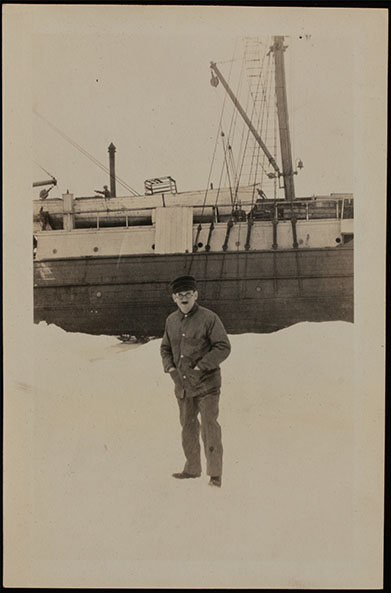

Ridley makes his debut appearance in the album posing on the ice with the Thetis as background, thus establishing his own presence on this northern voyage. While not included in the album, Ridley’s first pictures of the journey show fellow passengers on deck. Early 20th-century advances in technology had made photography more accessible, and posing for photos and snapping shots of the crew and the LHCC fur traders who would be wintering over at the new posts was part of social life on the Thetis. Without the need for extensive training or elaborate technical knowledge, fur traders like Ridley – but also camera-wielding missionaries, government officials, scientists and even tourists – were able to create visual records of their time in the Canadian North.

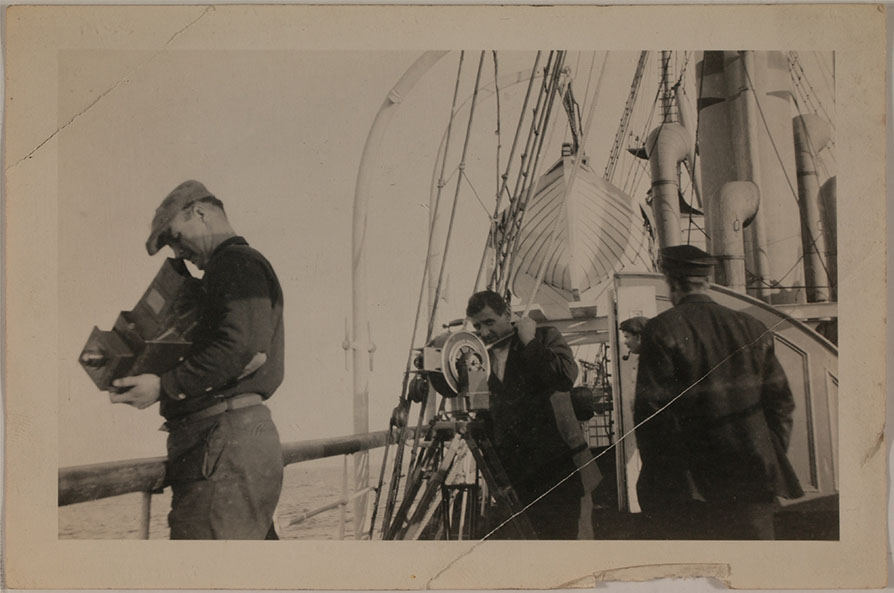

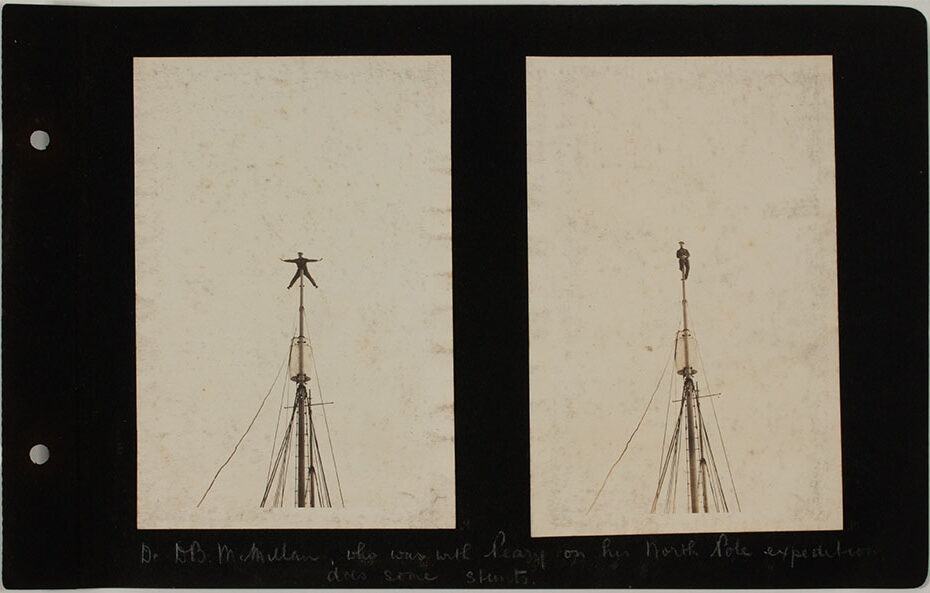

Experienced Arctic traveller and keen photographer Donald B. MacMillan, on board as a consultant for Lamson and Hubbard, had also brought his motion picture camera along on the trip. Ridley took a number of photographs of MacMillan performing aerial stunts, balancing at the top of the mast.

Following the voyage, MacMillan wrote to Ridley asking to borrow negatives of these northern pictures so he could add them to his own collection, which he later used in his illustrated lectures. When he returned Ridley’s negatives by post, MacMillan included some of his own prints. Once back south, northern photos were often exchanged with fellow passengers, eventually making their way into albums that were put to both personal and professional use.

Northern landscapes

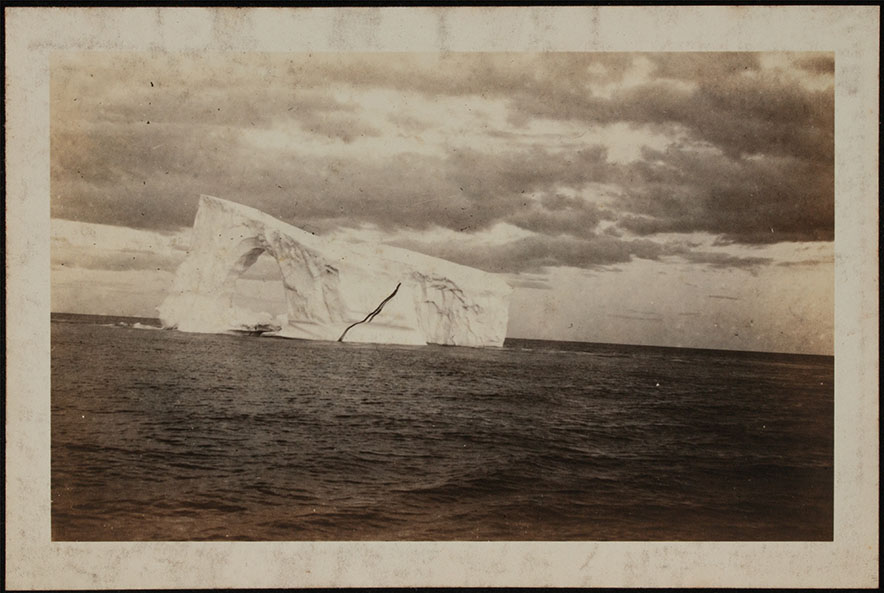

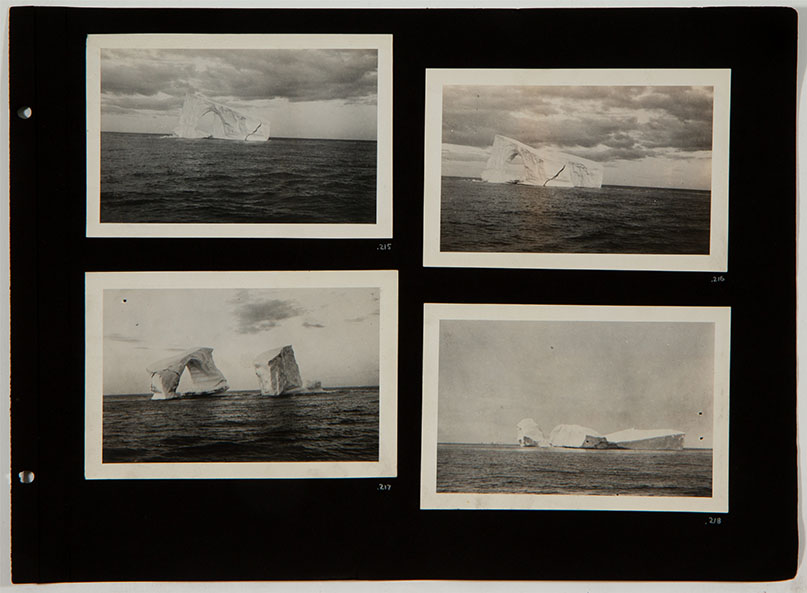

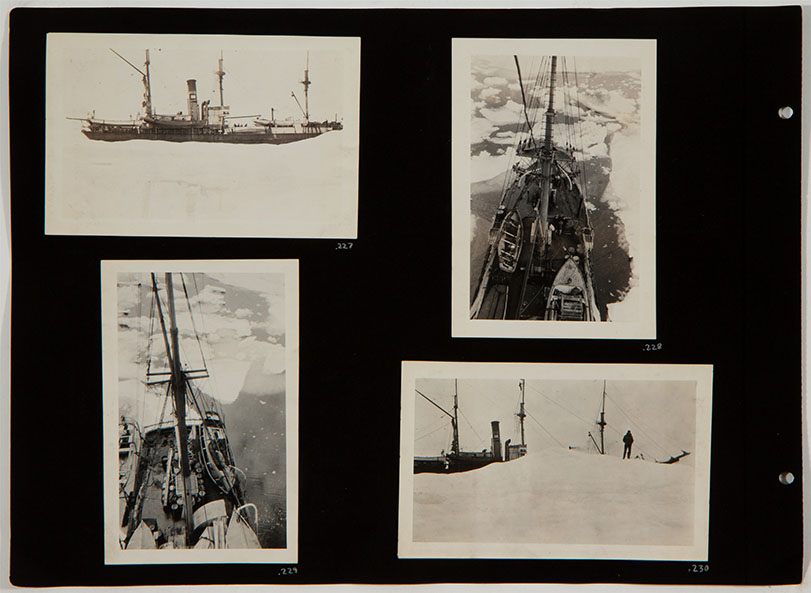

Ridley’s Thetis album begins with views of Battle Harbour, on the Labrador coast, that show the crew loading coal during this first stop on the voyage. As the ship headed further northward, Ridley turned his attention to the unfamiliar and spectacular environment. Icebergs surround the ship, and at one point Ridley counts over a hundred, noting in his journal: Photographed one magnificent berg in the shape of an arch (July 26, 1920). Further up the coast the ice thickens: Pans so close together that in the distance it looks like a solid mass, he wrote. Took many photographs of ice & vessel breaking through ice. This is a weird sensation at first but one gets used to the bumping & rocking of the vessel also the grinding as we smash into & over lumps of ice weighing tons (July 29, 1920).

Because of concerns over thick ice, fog and heavy winds, it was decided not to attempt a landing at Port Burwell, a required Canadian Customs port of call located on Killiniq Island, at the mouth of the Hudson Strait. Commenting on pictures he took the following day of the Thetis fastened up against an ice floe, Ridley remarked: These may have some effect with the Customs in Ottawa to demonstrate what sort of conditions a vessel in these waters has to put up with (August 1, 1920). He was clearly considering an applied use for his photographic practice, confident the camera would supply visual evidence that could be used to justify some of the decisions and actions taken during the northern voyage.

Colonial encounters

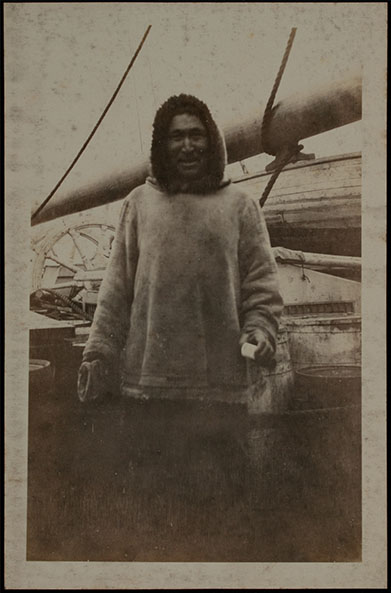

A few days later, approaching Cape Wolstenholme (Anaulirvik), a boat appeared out of the fog with ten Inuit on board. Inviting the “headman” onto the ship, the Thetis team learned that he and his companions were from Wakeham Bay (Kangiqsujuaq), further up the coast, and that they traded with the HBC, which had supplied their boat. As Ridley recorded in his journal: We gave the Eskimos presents of tobacco, biscuits, molasses & a pipe & told them that we were a new Company come to trade with them & showed them our flag. Took photographs & left them all smiles & evidently grateful for our presents (August 3, 1920). So, gifts were exchanged, the Lamson and Hubbard company symbol unveiled and photographs taken. The caption accompanying one of these photos in the Ridley album records the English translation of the headman’s Inuktitut name, while also revealing the importance of the occasion to Ridley: Mr. Sandfly – the first Eskimo we met.

What thoughts come to mind as we view this full-length portrait of a smiling man dressed in a parka, with the ship’s rigging in the background? Was he smiling out of gratitude, as Ridley’s journal entry suggests? Or was he presenting himself for the camera in a way that had been learned from other photographic encounters? The image serves as a reminder that photography does not offer an objective representation, but rather records a historical moment whose context is often hidden from the present-day viewer. The taking of photographs is conditioned in part by the power relations between the image-makers and those pictured.

Flying the flag at Chesterfield Inlet: establishing a physical and visual presence

On August 8, after sailing through more ice and inclement weather, the Thetis arrived at Chesterfield Inlet (Igluligaarjuk), on the west coast of Hudson Bay. By the early 20th century, this site, inhabited by Inuit for thousands of years, had become a gathering place for trade and employment, boasting an HBC trading post and a Roman Catholic mission station, both established in 1911.

The day following the arrival of the Thetis the Lampson and Hubbard flag was hoisted – and photographed – as a tangible symbol of the LHCC’s “challenge” to the HBC, so clearly spelled out in the picture’s caption. Over the next two weeks, Ridley supervised the unloading of the ship’s cargo and the construction of the new post building. Several images depict the building’s progress, firmly establishing the new company’s presence both on the ground and in the visual record created by Ridley.

Further colonial encounters

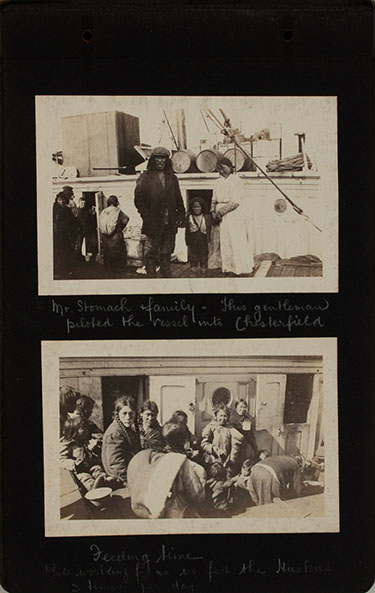

The success of Ridley’s voyage to Hudson Bay depended not only on establishing posts and leaving them equipped with traders and goods, but also on building trading relationships with the local Inuit. The majority of the album photos from the extended stay at Chesterfield Inlet are group and individual portraits of Inuit. Many were shot on board the Thetis during the meal breaks that were part of the compensation for assistance with the unloading operations, and several depict Inuit women carrying rocks for the post building’s foundation.

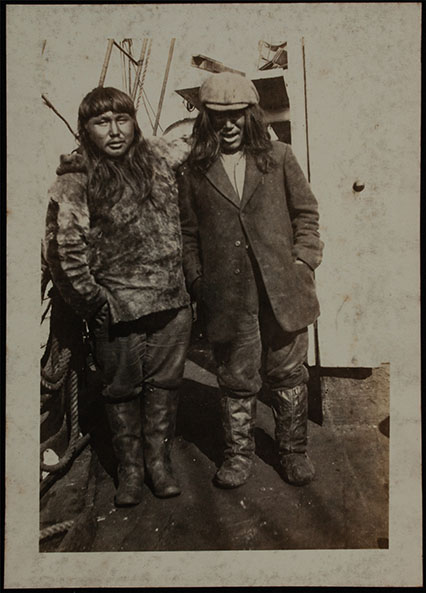

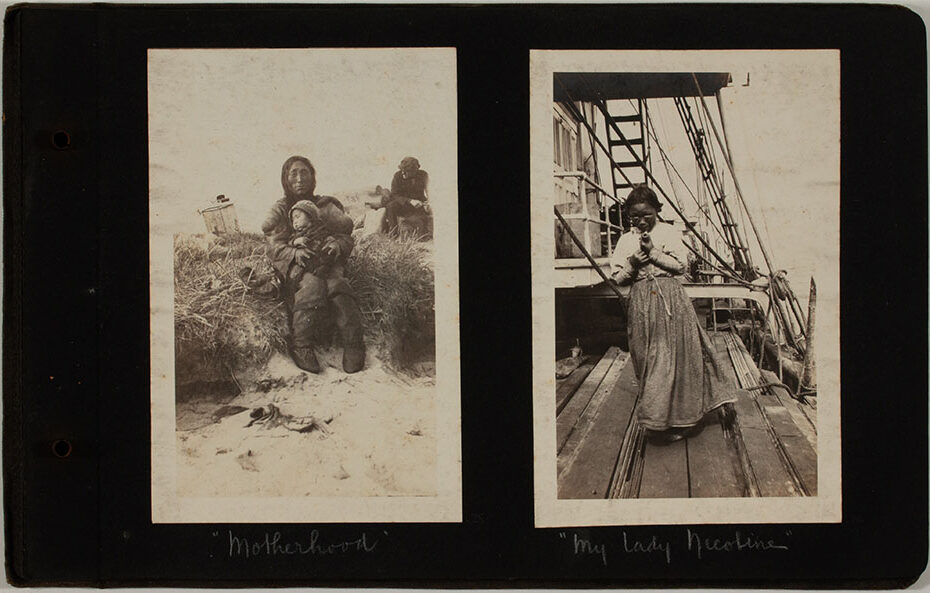

The caption of one of these photographs identifies two men, Kublo and Mr. Stomach (presumably the English translation of his name in Inuktitut). Ridley’s caption for another image of Mr. Stomach, pictured with his family, identifies him as the man who piloted the Thetis into Chesterfield Inlet, indicating a measure of personal connection. Overall, however, the Indigenous people photographed by Ridley remain anonymous, and his captions tend to emphasize their otherness and to reinforce stereotypical views: Eskimo ladies at Chesterfield, The smile that won’t come off, Motherhood, Churchill Chickens. Yet at the time the photographs were taken, Ridley appears to have established a certain rapport with the Iocal Inuit, for they face him and his camera straight on, seemingly participants in the exchange.

The voyage continues: Churchill and Cape Wolstenholme

There is a similar pattern to the Thetis album’s portrayal of the vessel’s next two destinations: Churchill, further south on the western shore of Hudson Bay (arrival August 25), and then back to Cape Wolstenholme (Anaulirvik), on Hudson Strait – the most northerly point of Quebec (arrival September 3). Images of the new post buildings under construction are followed by pictures of local Dene and Inuit people who, Ridley hoped, would choose to trade with Lampson and Hubbard.

Several of the Churchill photographs feature a visit on August 28 to the remarkable ruins of Prince of Wales Fort, built by the HBC in the 18th century. Ridley poses at the Fort with local HBC representatives and members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, accompanied by their spouses – an important visual reminder of the part played by women in these northern settlements.

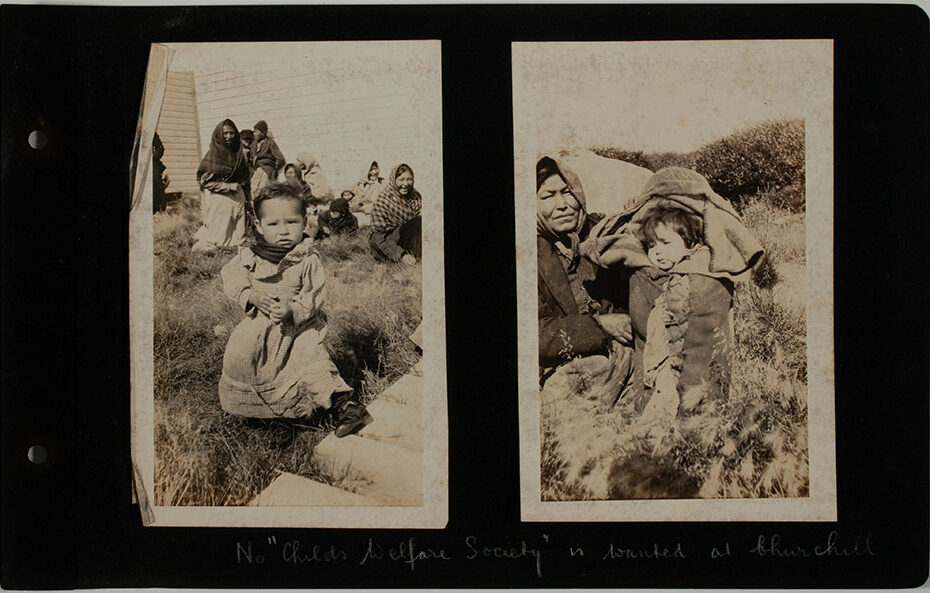

Two striking images focus on Dene children: in one, a young child gazes boldly at the camera dressed, like the women and children in the background, in Western-style clothing; the other, which shows a baby swaddled in a cradleboard, offers proof of enduring cultural practices in the realm of childrearing.

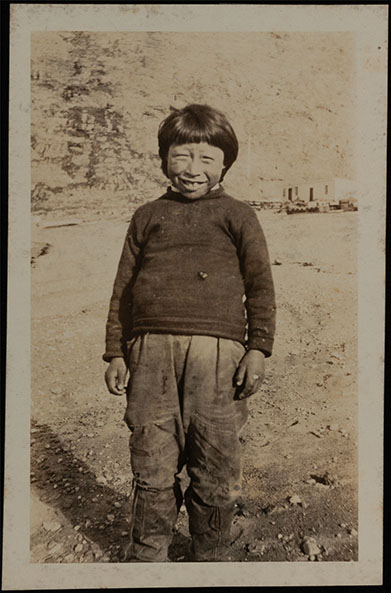

At Cape Wolstenholme the location of the LHCC post building was contested by visiting HBC District Manager Ralph Parsons, and the album features several long shots of the harbour with arrows pointing to the LHCC and HBC buildings. The sequence ends with an image of two Inuit in kayaks bidding au revoir to the Thetis crew, followed by a full-body shot of a young Inuk boy with the new LHCC post in the background, which Ridley optimistically captioned: A future hunter for the LHCC.

The job done

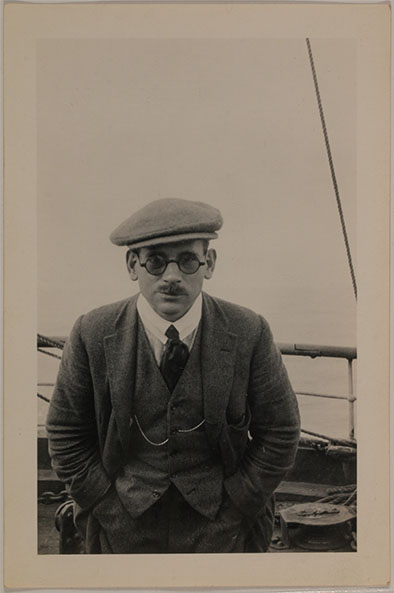

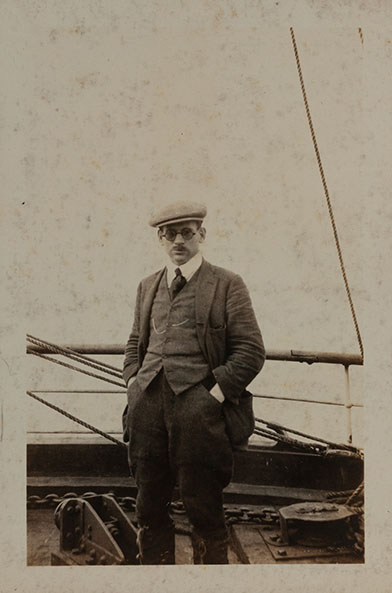

As they headed south, Ridley snapped a few more shots, noting in his journal: Managed to get some fine photographs of ice bergs today – also took groups of the after crowd on the ship (September 12, 1920). A group photo of Ridley and several crew members on deck conjures a sense of camaraderie, although in his journal Ridley had expressed concern that the behaviour of the ship’s captain could threaten the mission. The album concludes with a portrait of Ridley dressed in a three-piece suit, hands in pockets, accompanied by the telling caption: RLR – The job done.

Part of a general effort to make the North familiar and understandable, the album of Ridley’s 1920 voyage to Hudson Bay and the rest of his collection at the McCord Stewart Museum document the region during a time of pivotal change for Indigenous northerners. Shaped by his particular personality and approach to image-making, Ridley’s black and white photographs contribute to the construction of a visual vocabulary of the Canadian North, one that is constantly growing and being made more accessible thanks to digitization projects like this one.

* The titles accompanying the digitized versions of Ridley’s photographs that appear in the Museum’s Online Collections have in a number of cases been simplified and shortened.

Further reading

Heather Elliot, “Over the Waves: SS Thetis.” Original Shipster blog post, April 25, 2017.

https://www.originalshipster.com/blog/archives/1205

Mia Fineman, “Kodak and the Rise of Amateur Photography.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004.

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/kodk/hd_kodk.htm

Emily Henderson, Napatsi Folger, Niap (Nancy Saunders), Jordan Angunayuak Carpenter and Jason Sikoak, “Atiq (Naming Your Soul).” Inuit Art Quarterly, October-November 2020.

https://www.inuitartfoundation.org/inuit-art-quarterly/special-series/naming-series

Donald B. MacMillan Collection. Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, Bowdoin College (includes photographs of the 1920 Thetis voyage).

https://www.bowdoin.edu/arctic-museum/collections/index.html

Arthur J. Ray, The Canadian Fur Trade in the Industrial Age. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990.

Peter J. Usher, Fur Trade Posts of the Northwest Territories 1870-1970. Ottawa: Northern Science Research Group, Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, 1971.

http://parkscanadahistory.com/publications/north/nsrg-71-4.pdf