The Cowans’ Fancy Dress Ball

Revisiting a ball from 100 years ago, through photographs and costumes of those who attended.

November 12, 2024

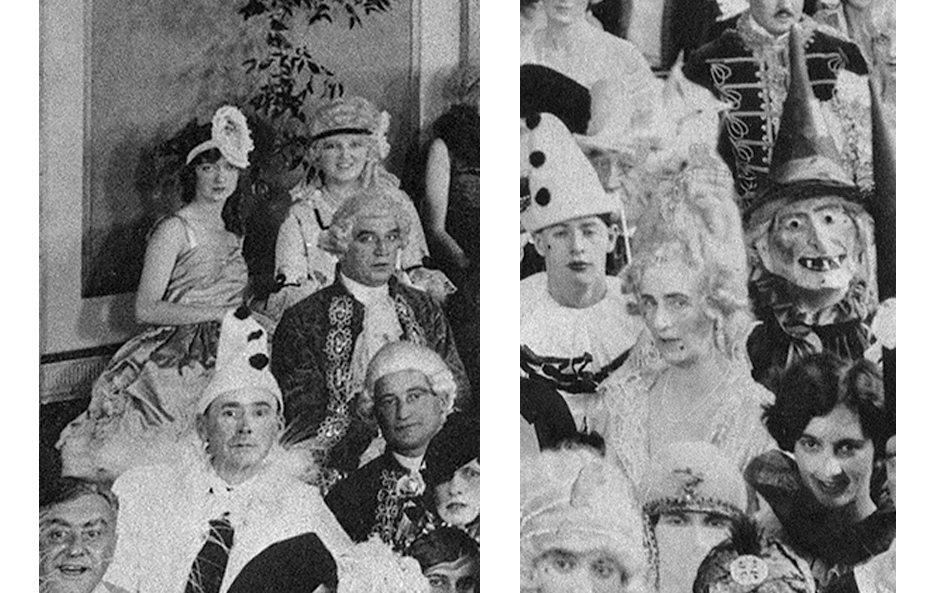

This flash photograph was taken at a few minutes past midnight on November 14, 1924, in the ballroom of the Mount Royal Hotel. Each guest at the lavish costume ball hosted by Mr. and Mrs. Percy Cowans in honour of their daughter Anna received a print of the quickly developed image as they left in the wee hours of the morning.

Souvenir of a grand ball

The image also appeared on the second page of the Montreal Star the next day, along with a lengthy list of the guests and descriptions of their costumes. It looms larger than life on the cover of the book Costume Balls: Dressing Up History, 1870-1927. Displayed in the exhibition in its actual size of 27 x 47 cm, its presence is more discreet, although on a nearby touch screen, visitors can enlarge it to zoom in on details.

Some 750 members of Montreal’s anglophone elite were in attendance at the private costume ball to celebrate Anna Cowans, who had made her début the previous year. But neither the hosts nor all the guests appear in the image. A number of other portraits from the Notman Studio and extant costumes help shed light on the characters portrayed in the ballroom that evening, and reveal some of the assumptions and aspirations of this privileged group.

| Step into the world of Costume Balls: Dressing Up History, 1870-1927 through blog articles, video interviews, behind-the-scenes photos, and much more! |

The Cowans and their characters

As was common in the previous century, many ball guests took their inspiration from history, including the entire Cowans family. Percy Cowans portrayed a character from the play A School for Scandal, in a black coat with gold trim, black satin knee breeches, a lace jabot and cuffs, and a white wig. Mrs. Cowans came as “A Lady of the Thirteenth Century,” in black velvet with ermine trim, and a tall hat embroidered in silver, with a large draped veil.

Anna Cowans chose a male character, “Sir Peter Teazle,” from the same play, in a plum-coloured eighteenth-century style costume. A mere 20 years earlier, it would have been taboo for a woman to appear in masculine-gendered dress, and to strike such a masculine pose for the camera. In fact, several nineteenth-century taboos had disappeared by the time of this ball. For instance, guests wore masks, which they removed just before the flash photograph was taken.

Nonetheless, ball-goers did not stray too far from prevailing standards of modesty. Winifred Tait’s rendering of the character “Eve” sidestepped any allusions to nudity, with her “short tunic of green leaves, caught at the shoulder with an apple, with a sequin snake twined round the waist, and brown sandals, and her hair loose, held in place by a wreath of leaves.”1

A Peacock

Bessie Molson attended the ball as “A Peacock,” in a costume featured in the exhibition Costume Balls: Dressing Up History, 1870-1927. Its materials were all the height of fashion. The trouser silhouette, however, was a daring Eastern-inspired departure from accepted attire for women, reminiscent of the creations of Paul Poiret and illustrator Erté for Poiret’s famous “The Thousand and Second Night” ball of 1911.

In a shade then known as “ashes of roses,” a silk satin lightly boned camisole with rhinestone straps creates a low-waisted effect over the full trousers. Both pieces are ornamented with vertical rows of rhinestones and small pieces of peacock feather. A silver lamé turban features rows of rhinestones overlaid on the front in a lattice effect, anchoring a graduated row of tall peacock feathers with eyes. We have been fortunate to locate an illustration that appears to have served as the inspiration for her costume.

Only a small fragment survives in the Notman Studio’s records of a group photograph of Bessie and her friends, but fortunately it was printed in its entirety in a New York society journal that covered the ball. The full impact of the headdress is best appreciated from the photograph where Bessie Molson stands at the back of the group.

Racialized portrayals

Bessie’s husband Col. Herbert Molson, who was not photographed in this smaller group or the larger one, came as “An Indian Rajah.” Only his turban survives from his costume, described as “cloth of silver trousers, fitting to the ankle, orchid satin coat trimmed with silver and gold lace, cerise satin sash edged with fringe, gold and silver turban with silver cockade, and cerise mask.”2

Many ball-goers donned garments and accessories borrowed from the cultures that they attempted to portray, along with dark makeup. This turban was made for the occasion. Like Bessie’s costume, it bears the label of Windsor Bazaar, a local shop in operation from the 1890s through the 1920s that was known for its high-end evening dresses.

In the absence of Molson’s costume, we are fortunate to be able to imagine what it looked like because of another image of a guest whose character and costume description corresponded closely to Molson’s. Artist Alphonse Jongers also came to the ball as “A Rajah” and posed for a photograph alongside well-known actress Martha Allan, who represented the “Mad Tzarevitch of the Russian Ballet.”

At this ball, like at others where racialized portrayals were not strictly forbidden in the invitation, guests brought them out in full force. Such representations bear witness to a shared vision of exclusion—who they portrayed as “Other,” often with an incongruous mix of cultural objects and elements created as costume. Many stand out for the way they contributed to normalizing whiteness and exerting racial control.

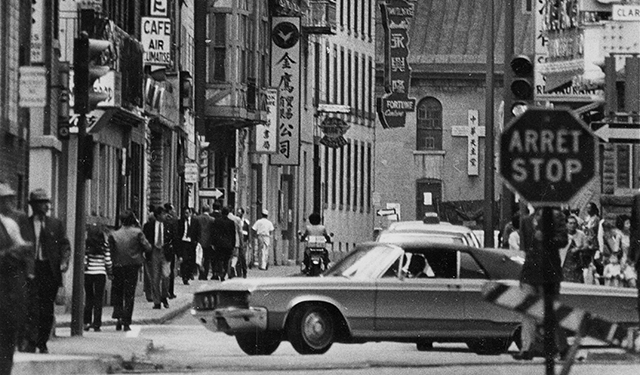

A significant number of guests came as Chinese characters, which reflects the growth of that racist device in popular culture since the late nineteenth century. Given that Canada had banned all Chinese immigration in 1923, their numbers wielded collective power as reminders of the containment of a perceived racial threat. One of the Chinese characters was Sir Arthur Currie, Principal of McGill University, who posed with Bessie Molson’s group, above. Another was Senator Smeaton White. Nor were such expressions limited to guests who appropriated racial stereotypes. Four men attended the same ball as Ku Klux Klan members; one can be seen in the foreground at the centre.

Other surviving costumes

John Wilson McConnell ranked amongst Canada’s wealthiest businessmen. After acquiring a sugar refinery, he broadened his interests to include newspaper publishing. He was also one of Canada’s most generous philanthropists. While his wife Lily Griffith McConnell occupies the most prominent position in the right foreground of the flash photograph, he is nowhere to be found. Yet we know from newspaper articles that he attended the ball in this blue eighteenth-century style costume.

He wore it again in 1927 to Narcisse Pérodeau’s Historical Ball in Quebec City, but was only finally photographed in it in 1955, the year when another historical ball coincided with the couple’s fiftieth wedding anniversary.

McConnell thus wore the costume over a thirty-year period, getting the most from his investment in the very best quality that could be had at that time, commensurate with his wealth.

Popular and creative characters

The most popular characters on the guest list were “Pierrot” and “Pierrette.” Spanish-inspired characters took second place.

Matching descriptions from newspaper articles to portraits reveals some of the intended humour in other portrayals. On the far left against the wall is Nora Hodgson as “A Powder Puff,” with the beauty accessory on a headband. She was one of three women to choose that character. Immediately to the left of a witch with a papier maché mask in the centre is Mrs. Beardmore as “A Permanent Wave,” a reference to another recent beauty practice, in a silver dress with a curled hairstyle of dizzying height.

Unfortunately, most of the other guests in the crowd scene are impossible to identify. Nonetheless, the image remains captivating 100 years after it was taken, and the multiple copies that have been offered to the Museum over the years bear witness to its impact as a cherished souvenir.

NOTES

- The Gazette (Montreal), November 15, 1924, 5.

- The Gazette (Montreal), November 15, 1924, 5.