1874, opening of Île Sainte-Hélène Park

Explore the history of Île Sainte-Hélène Park, 150 years old almost to the day.

June 21, 2024

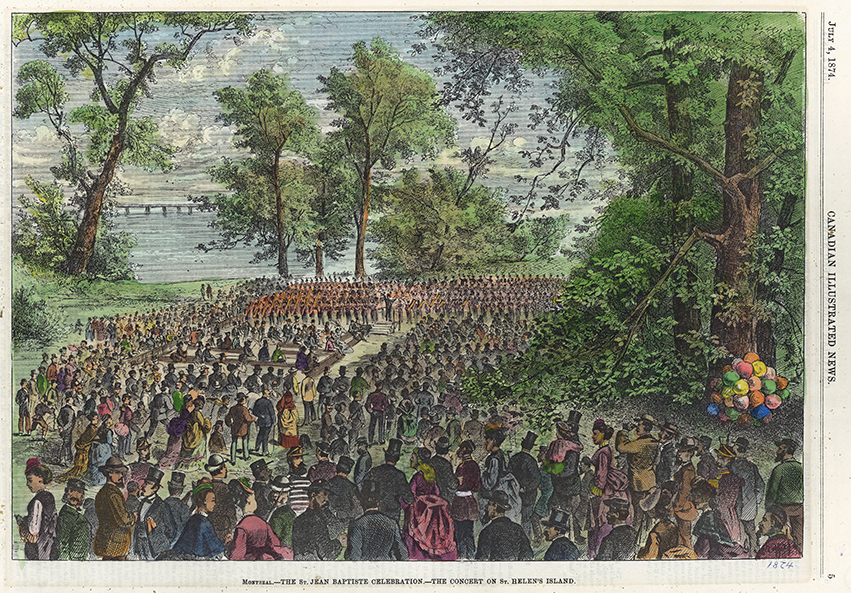

One hundred and fifty years ago, on June 24, 1874 – Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day – Île Sainte-Hélène Park opened to considerable fanfare. Montreal’s first major public park, it was inaugurated almost two years before Mount Royal Park (May 24, 1876).

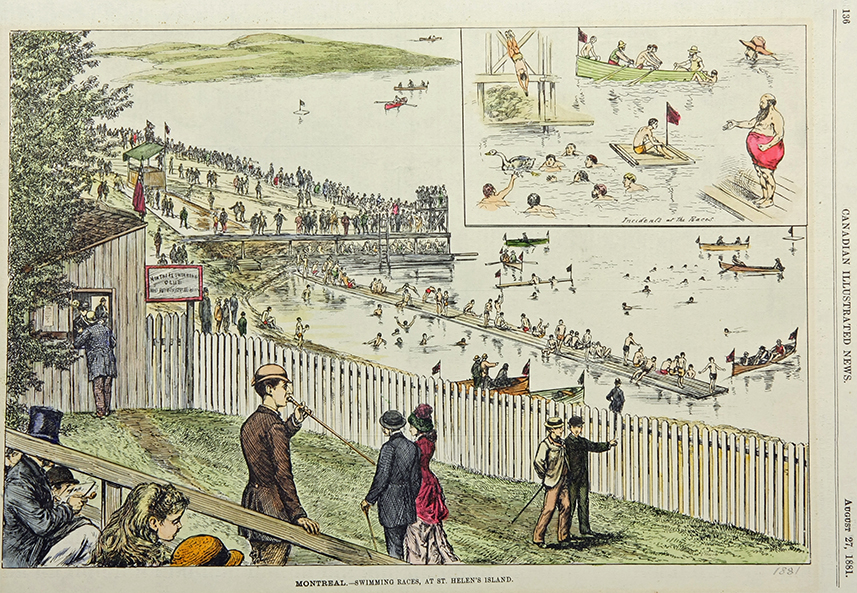

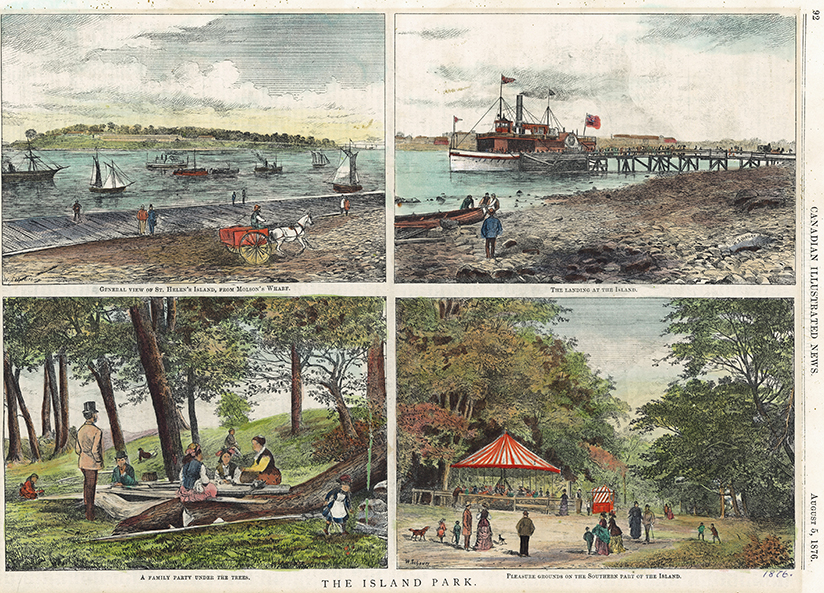

The event got extensive press coverage. The pioneering and highly popular illustrated magazines in Canada, L’Opinion publique and Canadian Illustrated News, in particular, provide a fascinating visual account of the early days and first decade of this vast public space.

| To learn more about the island before it was a public park, read the article Île Sainte-Hélène: Before it was a public park |

Even before the official opening, Montreal’s civilian population had been allowed access to the island on special occasions, such as July 1, 1873 – Dominion Day – and had evidently been captivated by the site’s idyllic charms.

The park’s opening festivities included a huge picnic attended by 6,000 people and a grand concert featuring 600 singers and 23 bands of various kinds.

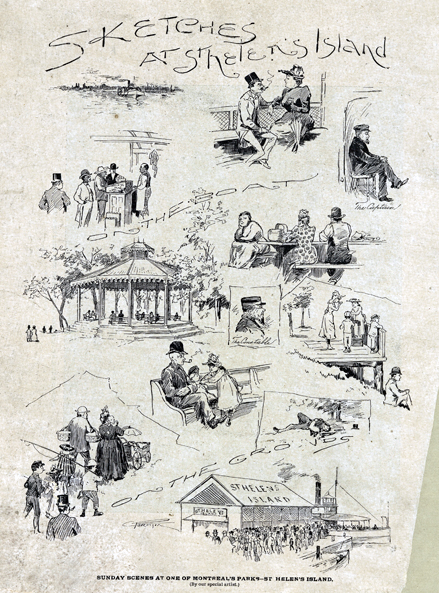

A couple of weeks later, the Canadian Illustrated News published a series of sketches by the artist W. Scheuer that show views of different spots on the island and of its often dilapidated buildings. The general impression is of a rather neglected but romantically bucolic place being gradually overrun by nature.

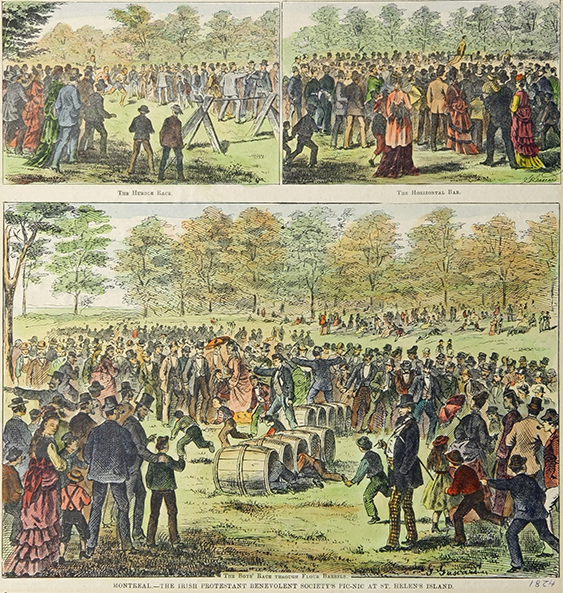

After the inauguration, Montrealers soon became regular visitors to the island and its park. The various national associations representing the city’s cultural communities frequently held picnics there, even helping to fund their activities by charging double for the ferry fare on those days.

The island’s popularity would only increase in the decades to come: hundreds of thousands of people flocked there each summer, and the crowds were particularly dense on Sundays and official holidays. In order to maintain order and prevent inappropriate behaviour, strict regulations were imposed – for example, the park was only open during daylight hours – and a guard and a small corps of security officers were hired.

Picnics and sporting activities all the rage

As soon as its “people’s park” opened, Île Sainte-Hélène became a favourite picnic spot. This inexpensive and pleasant activity, bringing together family and friends, would long remain one of the most popular ways of enjoying the island’s beauty and cool breezes.

Physical activities and sports were also much practiced on the island, long before the 1976 Olympic Games. Swimming was especially popular. The Montreal Swimming Club, founded shortly after the park opened, was given permission to operate at the northern tip of the island, in an area normally restricted to military personnel, on the condition that it only allow access to its members.

Later, during the 1930s, a lagoon was constructed on the south side of the island to allow safe swimming in the river. After the Second World War, owing to pollution in the Saint Lawrence, the Pavillon des baigneurs was built. Still in operation today, it was Montreal’s first public outdoor swimming pool. The Jean-Doré beach, which would come into being around 1990, uses a natural filtration system to ensure the water is suitable for bathing.

Large gatherings and major events

The island was an ideal venue for large gatherings and major events like festivals and outdoor concerts. It could actually have been dubbed “Kids’ Island,” since vintage newspapers and pictures reveal that it served very often as the site of activity days attended by hundreds, sometimes thousands of children from all over Montreal. The kids would apparently gather first in one or other of the city’s various parks before being taken to the island for a day of communal outdoor fun – incidentally giving their parents a bit of a break.

Natural oasis versus fairground

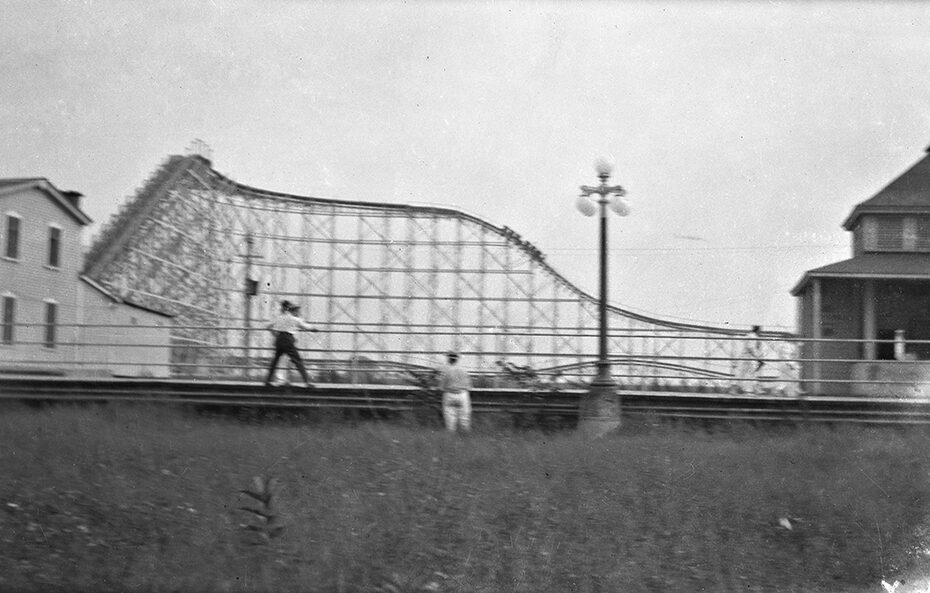

Throughout the history of this great park there has been ongoing tension between the desire to preserve its natural environment and the idea of turning it into fairground. Although the aim of the park was to give the general population, particularly the working classes, access to a haven of nature, there were those in the early 20th century who dreamed of turning it into a Montreal version of Coney Island, a “veritable people’s Eden” (La Presse, May 20, 1905) modeled after the famous New York amusement park.

In fact, from the park’s earliest years, entrepreneurs had offered games and rides on the island, but competition from other fairgrounds was fierce, especially Sohmer Park (1889-1919), located opposite Île Sainte-Hélène on Montreal’s shore, just west of the Molson Breweries, and King Edward Park (1910-1922), on Île Grosbois, in the Boucherville archipelago. Military authorities on the island also restricted the construction of new installations.

It would not be until the creation of La Ronde, for the 1967 International and Universal Exposition (Expo 67), that the dream of a real amusement park became a reality, and at that time a compromise was reached: by building the fairground on the site of the former Île Ronde, henceforth linked to Île Sainte-Hélène by major earthworks, it proved possible to leave the island’s natural milieu largely untouched.

Huge transformations

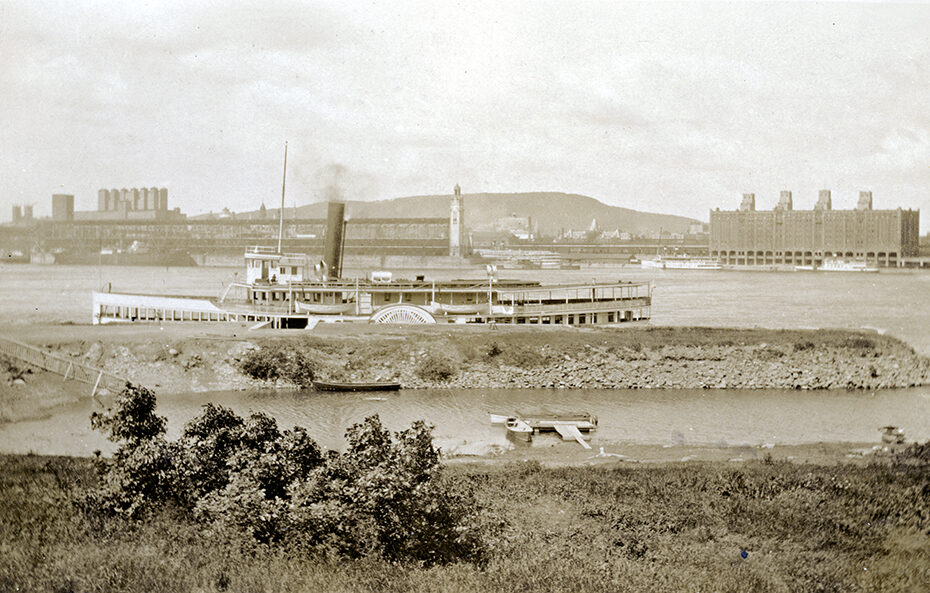

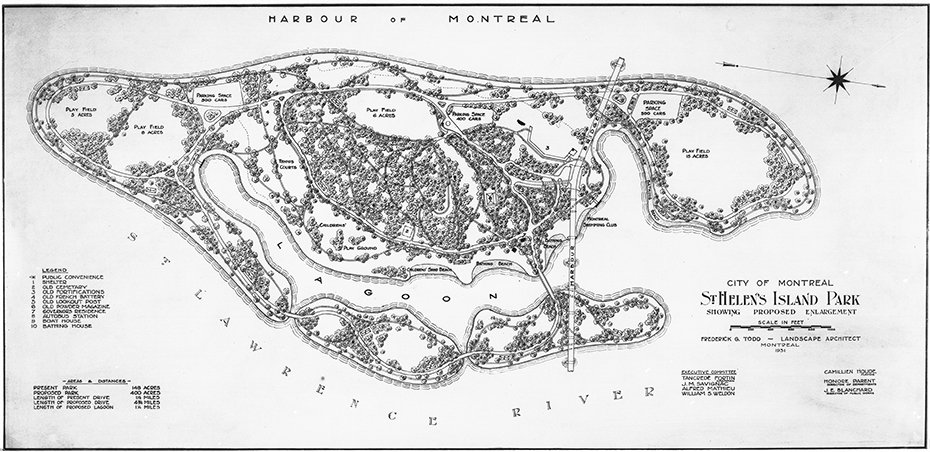

Nevertheless, the island underwent radical changes during the 20th century. Development projects were proposed as soon as the park opened, but it was during the 1930s that things really geared up, following construction of the Harbour Bridge (renamed the Jacques Cartier Bridge in 1934) and the arrival of cars on the island.

Frederick Todd, a pioneer of landscape architecture in Canada (and a disciple of Frederick Law Olmsted, responsible for the design of Mount Royal Park), came up with an ambitious master plan that involved the fusion of Île Sainte-Hélène with its neighbouring islands – a project that would not be realized until 30 years later, for Expo 67. But it was from the 1930s on that the modern park began to take shape, with the introduction of a number of leisure infrastructures that included the Tour de Lévis (1936), the Pavillon des baigneurs (1953, now the Aquatic Complex), the Hélène-de-Champlain restaurant (1955), the Stewart Museum (1955) and the Théâtre de La Poudrière (1957). Slowed by the Depression, work came to a standstill during the Second World War, when the federal government commandeered the island to establish Camp S/43, used to intern hundreds of British civilians of Italian origin.

The greatest transformation of all was obviously the one triggered by Expo 67, which would nearly triple the surface area of Île Sainte-Hélène by joining it to Île Ronde and Île aux Fraises, as well as creating virtually from scratch the large neighbouring island of Notre-Dame on the site of the former Île à la Pierre (or Île Moffat) by the importation of millions of tons of earth and rock, some of it excavated during construction of Montreal’s Metro system.

So much more could be said about the island, which with Expo 67 embarked on its story’s most exciting chapter. Taking the long historical view, we are left with the impression of a constantly evolving treasure, close to the heart of both Montreal and Longueuil, but separated from them by the fast-flowing Saint Lawrence.

References

Bolduc, Ginette et Danielle Dulude. L’île Sainte-Hélène et son gardien, 1896-1916, Longueuil, Société historique du Marigot, 1992.

Daignault, Sylvain et Paul-Yvon Charlebois. L’île Sainte-Hélène avant l’Expo 67, Québec, Les Éditions GID, 2015.

Desharnais, Josée. « La gestion des loisirs publics à Montréal : l’exemple du parc de l’île Sainte-Hélène, 1874-1914 ». Mémoire de maîtrise (histoire), Université de Montréal, 1998.

Gervais, Diane et al. Deux îles, un parc, une ville… : le parc Jean-Drapeau, au cœur de l’histoire de Montréal, Montréal, Société du parc Jean-Drapeau, 2017.