Regarding Mrs. Farquharson

Discussion between Zoë Tousignant, Curator, Photography, and Heather McNabb, Reference Archivist, on the process of researching two photographs in the Museum’s collection.

December 6, 2024

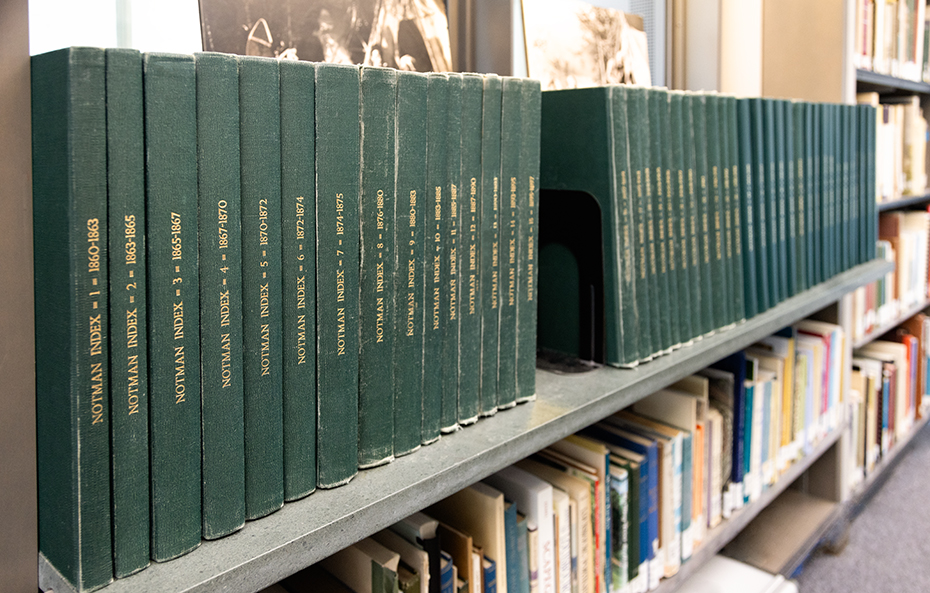

Michaëlle Sergile’s exhibition To All the Unnamed Women has led us to reconsider a few of the images held in the Notman Photographic Archives – the collection of about 200,000 glass plate negatives, 400,000 prints and hundreds of record books produced by the Montreal Notman studio between 1856 and 1935.

_____

Zoë Tousignant: The artist’s investigation of portraits of Black women, most of whom the Notman studio did not identify by name, drew our attention to one woman in particular, who appears in two separate photographs.

In the first portrait, from 1867, the subject looks to the right of the camera and rests an arm on a small table. She wears a voluminous silk taffeta mantle with beaded detail at the shoulders, slightly open to reveal horizontal stripes on her skirt, as well as a lace-trimmed bonnet tied at the neck with a large bow.

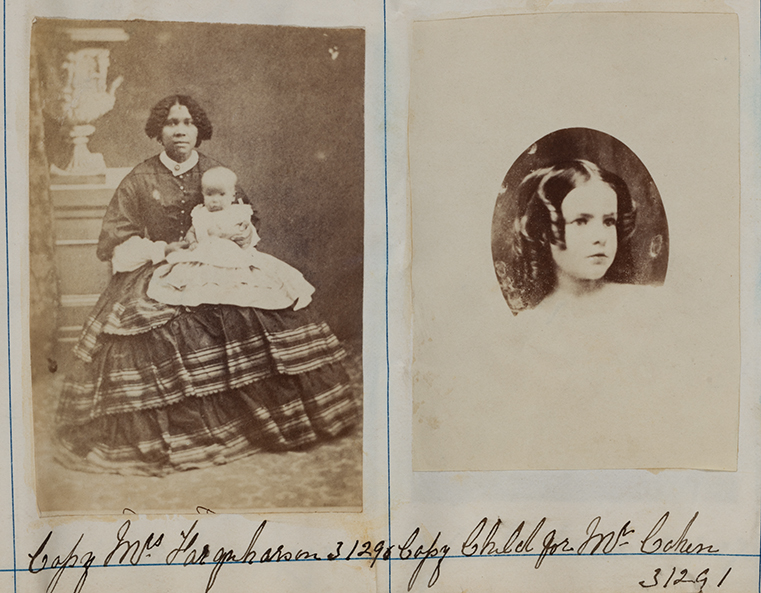

In the second portrait, from 1868, the same woman poses with a baby of about six months old. Here she wears a fashionable indoor dress, the pagoda sleeves and striped edging of each of the three tiers of the skirt being its most salient features.1 The baby in her lap appears light-skinned and wears a white gown. Both look directly into the camera, and they are seated before a painted backdrop representing a classical interior.

Can you explain how these two portraits were titled when Michaëlle Sergile first looked at them on the Museum’s database?

Heather McNabb : When Michaëlle Sergile first saw them on our database, the first portrait was titled Mrs. Farquharson, copied in 1867. The second was Nurse and baby, copied for Mrs. Farquharson in 1868. It was Michaëlle who brought the discrepancies between the two titles to our attention. Neither of these two titles appears exactly as it would have in William Notman’s time. Both are “caption titles,” initially generated by cataloguers, likely sometime in the 1960s, from the words written below the image in the original Notman studio records (occasionally rearranged for clarity), and with the addition of the date.

In the studio records, the original title was the same for both images: Copy Mrs. Farquharson.

In the first caption, the title was rearranged slightly by a cataloguer and the date added. The cataloguer of the second photograph, however, made an assumption and added “Nurse and baby” to the title. In addition, Copy Mrs. Farquharson was interpreted in this case as being a copy for Mrs. Farquharson. The seemingly simple addition of four words during the cataloguing process in the interests of “clarification” had a devastatingly important effect in this case – the possible subject of the photograph was rendered anonymous!

From quite early on, the Notman studio regularly made copies of photographs for customers. Copies, like photographs taken in the studio, could range from miniature photographs made to fit into a ring or a small locket up to large–format portraits in a frame.

Zoë: Right, the fact that these two portraits are copies is significant: in this case it effectively means that they weren’t taken by the Notman studio, since the Notman Photographic Archives holds most – if not all – of the negatives produced by the Montreal studio. It also means that the photographs were taken before the date on which they were copied. Based on both the style of dress and the type of portrait, it’s likely that they were taken in the late 1850s or perhaps the very early 1860s. But where they were made is not known, and why they were copied can only be speculated.

A copy is essentially a photograph of a photograph, and could be produced for a variety of reasons. Within the larger field of nineteenth-century photography, you often see single-image photographs like daguerreotypes and ambrotypes being re-photographed once these processes had become obsolete. The advantage of creating a new negative from an old photograph was the potential for making any number of prints. This may have been desirable when a family member died, for instance, or moved away. An image of the absent family member could then be cherished by several people.

You can usually see clearly when a photograph is a copy, since there is a deterioration in the quality of the image. For example, when daguerreotypes or ambrotypes are re-photographed, the metal surface of the original appears in the new photograph as what I would describe as blotchy dots. But in this case, we also know that the two portraits are copies because they were inscribed as such in the Notman studio’s Picture Books.

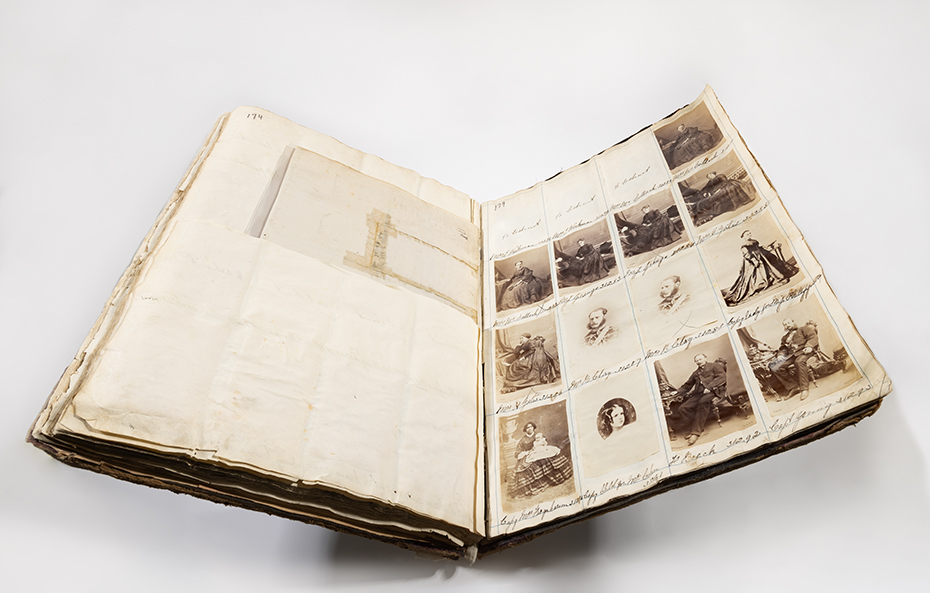

Heather: That’s correct. The Picture Books are essentially photographic albums that the Notman studio created as a record of their work. Each album is organized numerically, by the sequential number given to each photograph that the studio produced for a customer. Notman’s staff would inscribe a title in ink along with the number below the photograph pasted on the album page.

Most of the portrait titles were simply the customer’s name. For a group, often only the paying customer’s name was noted down, and the group could be titled, for example, “Mr. Smith’s group,” or “Mr. Smith and friends.” If the sitter was a child, and Mrs. Smith was ordering the photographs, the title might have been “Missie Smith,” or perhaps “Mrs. Smith’s baby.” Copies of photographs were indicated by the word “Copy” before a person’s name, as in our two “Copy Mrs. Farquharson” photographs. Unfortunately for us today, it seems to have been taken for granted by Notman’s staff during this period that “copy” meant “copy of.”

The Picture Book records suggest that the compilers made an effort to ask for the name of the individual pictured in the copied image. When the subject was unknown, a generic description was often supplied, such as “Lady” or “Child,” and, significantly, the name of the person who ordered the copy was added in most instances. The title became “Copy Child for Mr. Cohen,” as in this example, right next to the second “Copy Mrs. Farquharson.”

We can assume, given the examples on the album page framing Mrs. Farquharson’s portrait, that she is indeed very likely the subject here, and not the person for whom the photograph was copied. But we really wish Notman’s staff had added an “of” and made everything certain.

Zoë : We’re used to having the Picture Books as a research aid, but it bears repeating how rare and valuable a tool these are. When it comes to nineteenth-century studio portraiture, more often than not the identities of subjects have been lost. This is the case when you come across portraits on eBay or in antique stores, but also in museum collections. Exceptions are if the person portrayed is famous and recognizable, or if a family member has lovingly inscribed the subject’s name on the back of the carte-de-visite or cabinet card. The Notman studio’s records aren’t infallible, but they do allow us to start the research process on a firm footing. In this case, we begin with a name: “Farquharson.” What other instances of this name did you find in the studio’s ledgers?

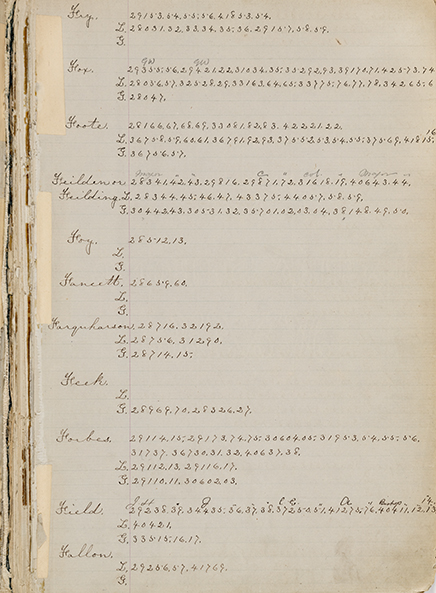

Heather: The name Farquharson appears in four other photographs between 1867 and 1870. We know this through the Index Book, another type of record from the Notman studio.

The Index Books contain the surnames of all the sitters who came in, and the surnames of the people appearing in copies, together with their photograph numbers. These books function as finding aids for the photographs arranged numerically in the Picture Books.2

When a customer came in to order a reprint of an earlier photograph, the alphabetical index would allow the staff to look up the number of the portrait, verify the numbered image in the Picture Book, and later find the negative (used to make the print), stored numerically on the shelves. And we still use William Notman’s carefully arranged original system today, particularly in the sections of the collection that have not yet been fully catalogued and digitized.

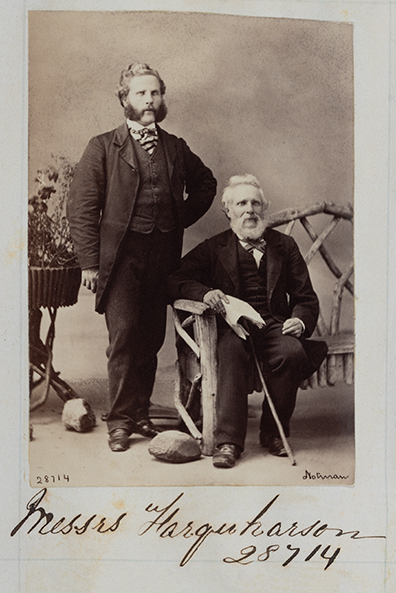

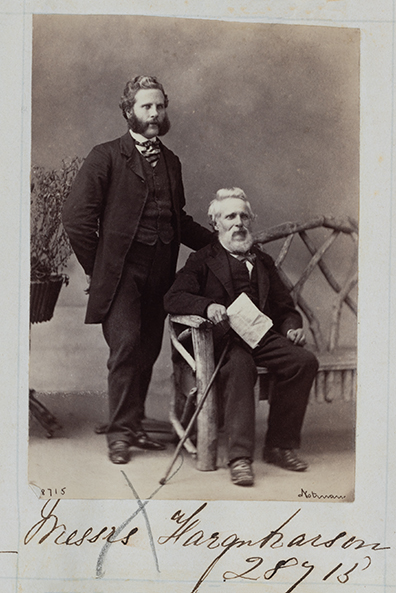

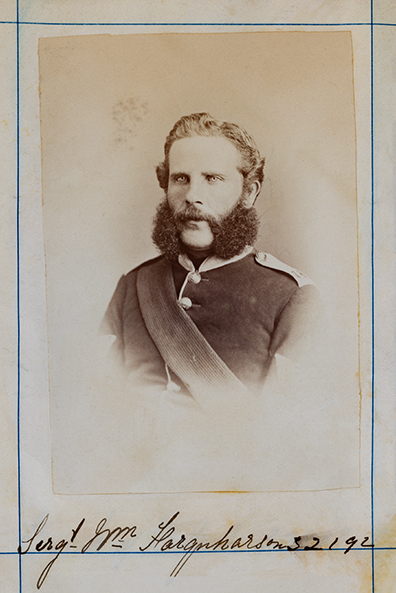

But to get back to the Farquharsons in the Index Book. I found a portrait of a small boy, Master Farquharson, taken in 1867, and two group portraits showing an older man seated with a younger man standing, titled Messrs Farquharson.3 Finally, the younger of the two men was photographed in uniform in 1868, the title allowing us to know that his first name was William and that he was a sergeant. The number seventy-eight on his shoulder indicates the British army’s 78th Highland Regiment of Foot.4

The numbers for Messrs Farquharson and Master Farquharson fit together sequentially, so it is logical in this case to assume that they, at least, are family, and came in together to have their portraits taken. It is intriguing to note that the 1867 copy of Mrs. Farquharson is not very far off numerically from the three male Farquharsons. It is easy to begin to speculate – could one of the Mr. Farquharsons have brought her portrait to the studio to be copied at the time of their sitting? Would Master Farquharson be the baby Mrs. Farquharson is holding in the second copy portrait?

Research into various newspaper, city directory, census and other historical records for Montreal have uncovered some interesting clues. Sergeant William Farquharson came to Montreal in 1867 with the 78th Highland Regiment of Foot. In March of 1869 he married a Montrealer named Isabella Rogers, and when the regiment was transferred to Halifax a few months later, William stayed behind in the city, pursuing his trade as a master tailor. In 1891, the census shows that his eldest son, James, is twenty-five, and working as a railway clerk. Too old to be the son of William and Isabella’s marriage in 1869, James is about the right age to be the “Master Farquharson” photographed in 1867. It’s not impossible to believe that James is also the baby sitting with his mother, Mrs. Farquharson, in the copy photograph.

Zoë: That’s fascinating! And I agree that, based on facial features, it’s not impossible that the baby pictured is indeed “Master Farquharson” and that he is Mrs. Farquharson’s child. It may be that the couple met before Sergeant Farquharson came to Canada, and it may be that she died not long before he settled in Montreal. This would explain why the photographs were brought to the Notman studio to be copied soon after his arrival in the city. Of course, more research needs to be done to confirm these hypotheses. A next step might be to try to find archival traces of Mrs. Farquharson in British historical records.

Heather: Absolutely! While speculating on the possible links between Sergeant William Farquharson, Mrs. Farquharson and young Master Farquharson can be a useful research strategy, the story remains fictional without archival information to back it up. Figuring out Sergeant Farquharson’s biography and movements while with the 78th Regiment of Foot could be one way to start the search. I’ve seen a few tantalizing clues so far – hopefully they will lead us to “Part Two” of our discussion!

Notes

1. The authors wish to thank Cynthia Cooper, Curator, Dress, Fashion and Textiles, McCord Stewart Museum, for providing invaluable information on the subject’s clothing.

2. There are forty-three Index Books in all, each one spanning a few years in the period from 1860 through 1935-1936.

3. A plural form of Mr., “Messrs” was commonly used to describe a group of men. Young boys were often given the title “Master,” and young girls “Missie.”

4. It is important to note, however, that the fact that Mrs. Farquharson is found in the Index Book alongside these other Farquharsons does not necessarily mean that they are all from the same family. The Index Books group all photographs under the same surnames together, whether or not those named were are related.