Anna Lois Dawson Harrington: Forty years of landscapes

Now remembered as an artist, during her lifetime she painted watercolours as a personal passion.

April 26, 2024

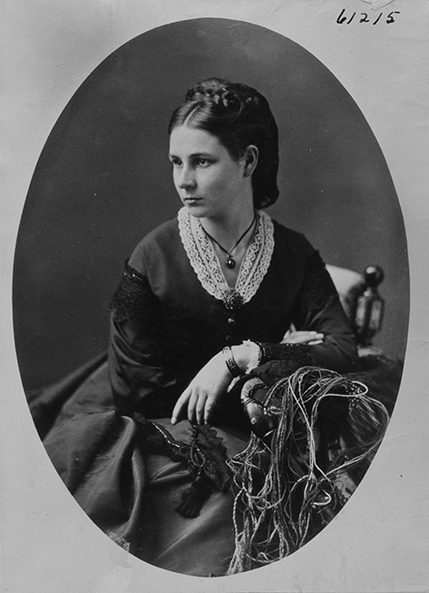

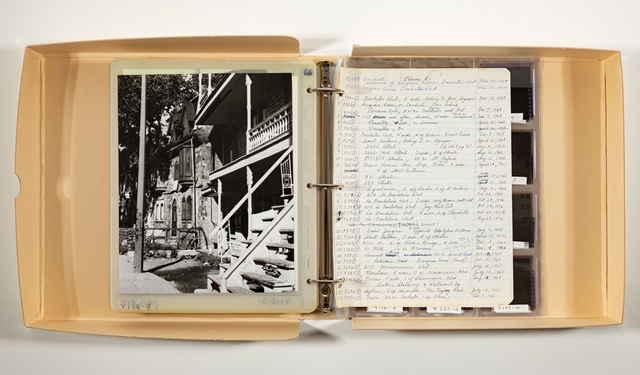

The Museum’s collections include over 200 watercolours by Anna Lois Dawson Harrington (1851-1917), most of them donated by her granddaughter, Anne Virginia Winslow-Spragge, the wife of Donald N. Byers. While Anna Lois is now remembered as an artist, during her lifetime, she pursued drawing and watercolours as a personal passion, a hobby that was one of the skills every well-educated young woman had to master, with varying degrees of success.

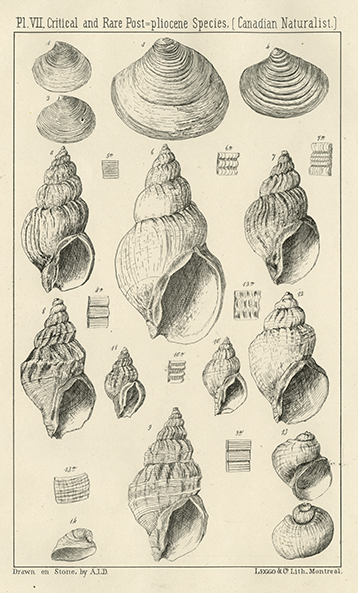

Anna Lois, however, had a real talent and love for drawing. In her youth, she illustrated the scientific works of her celebrated father, Sir John William Dawson (1820-1899), a geologist, paleontologist and principal of McGill University from 1855 to 1893, along with those of her brother, George Mercer Dawson (1849-1901), a Canadian geologist and surveyor.

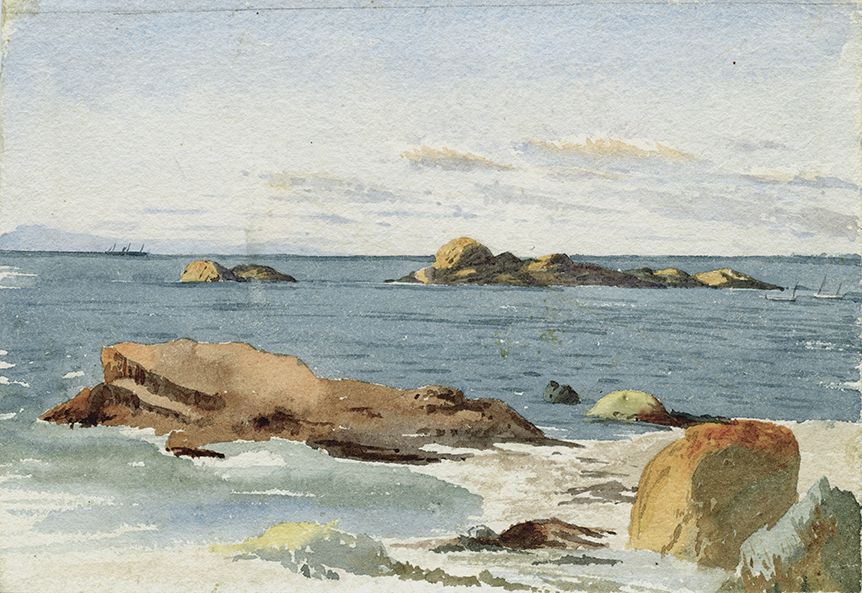

During summers in the village of Little Métis (today Métis-sur-Mer) at the gateway to the Gaspé Peninsula, she would paint landscapes of the surrounding coastal and wooded areas as often as her large family would allow her to.1

WHO WAS ANNA LOIS?

We know that Anna Lois was the daughter of Sir John William Dawson, the wife of professor Bernard James Harrington, and the mother of nine children but, beyond these generic definitions, who was she? Anna Lois’ watercolours and letters to her husband from Little Métis reveal a lot about her personality.2 Her paintings also clearly illustrate her love of nature. There are very few human figures in her landscapes, only the outline of children here and there—a form she did not master very well, in fact.

| See all of Anna Lois Harrington’s work on Online Collections |

She enjoyed spending time alone so she could focus on the details of the landscape, particularly the texture of the rocks on the beach. She was very fond of the enormous trees that rose to the sky like cathedrals. Loren Lerner has found passages in Anna Lois’ letters that demonstrate her powers of observation:

“Again and again in her letters, in a romantic language that discloses her vision of place, she sees the ‘tinted clouds’ (1875), the ‘little curls of the ferns coming up’ (1880), the ‘golden autumn fields that continue to fascinate me’ (1882) and the ‘great hills of cumulous clouds making endless reflections and shades in the water’ (1885).”3

Her private correspondence shows her to be affectionate, attached to her community, and very unpretentious. Faith, the reading of great works (notably the Bible), reason, and education were core values for her. Despite facing hardships, constant worry and financial pressures,4 she retained her strength of character and optimistic determination.

She probably would have liked to do research in the natural sciences and enjoy the same freedom as her father, brother and husband, judging from these words she wrote in a letter dated July 18, 1881:

After the rain on Saturday I went down to the shore in the quiet evening. I enjoyed it so much, tide full in, and sunset-glow in the West. I wish I more often could get away quite alone. I always feel so much better for it, the trivial pettiness that so often crusts over one’s life, melts away and the better thoughts can rise to the surface, and the eyes catch glimpses of the land that is far off, and of that kingdom of God which, though so nigh, is often invisible to us. The one thing I envy in man’s estate is his power to walk out of the house made with man’s hands, into the living temple of nature, whenever he pleases by night or day.5

The fact that she did not engage in a scientific or artistic career, despite her inclination and potential, did not change her desire to excel in the roles she was given.

FORTY YEARS OF LANDSCAPES

In 1875, her fiancé Bernard James Harrington, who went on to become an eminent professor of mineralogy at McGill University, gave her an easel for Christmas, an item that we now know she made very good use of, even though she had her doubts at the time:

Dearest Bernard, Thank you very very much for the beautiful easel. I only wish I could ever hope to paint a picture good enough to be worthy to put on it. But even if I cannot, the easel itself will always be to me a picture of your kind thoughtfulness.6

Bernard’s gift was inspired by the drawing lessons Anna Lois had taken in the 1860s in the various schools for girls that she had attended.7

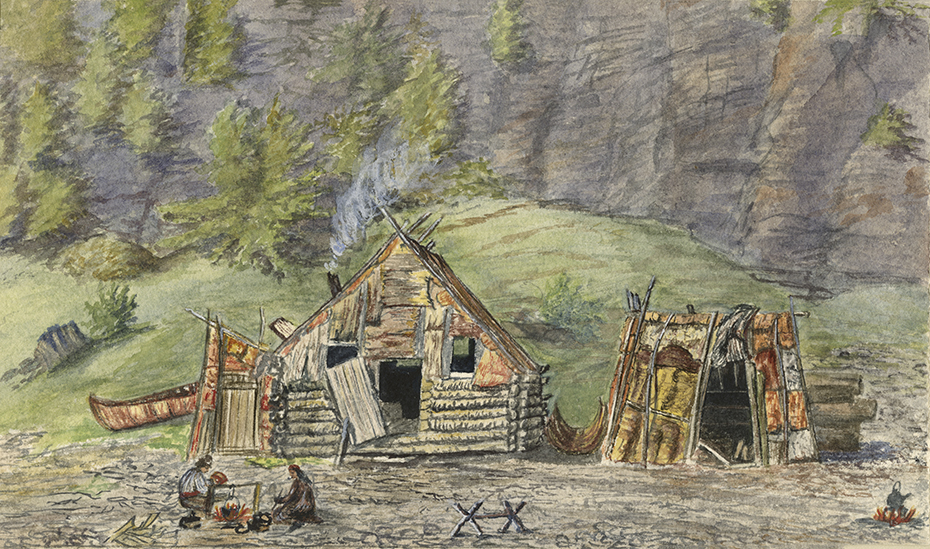

Later, in 1880, she would write that she would be happy if each year she could bring home to Montreal at least four pictures worthy of decorating the walls of her living room.8 Given her weighty domestic and educational responsibilities, Anna Lois’ consistent artistic output is both remarkable and admirable. Little Métis may have been her primary subject, but the Charlevoix area was another favourite. She painted a series of watercolours in this beautiful region as early as 1869, when she was intrigued by the presence of Indigenous people.

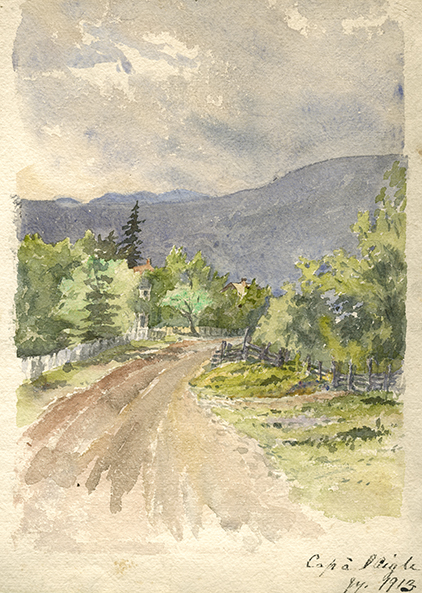

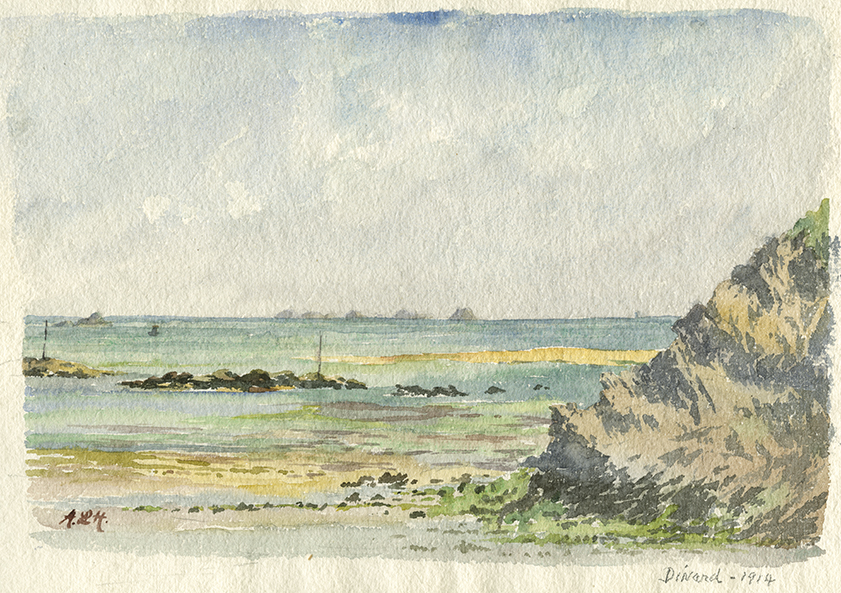

However, the delicate watercolours she created during her 1913 visit to Cap-à-l’Aigle best illustrate her talent and the evolution of her style. In addition, exquisite landscapes of Scotland and France came out of the trips she was able to take in the last decades of her life. Although not often represented in her work, Montreal was the subject of an exquisite view of Mount Royal ablaze in fall colours.

LITTLE MÉTIS

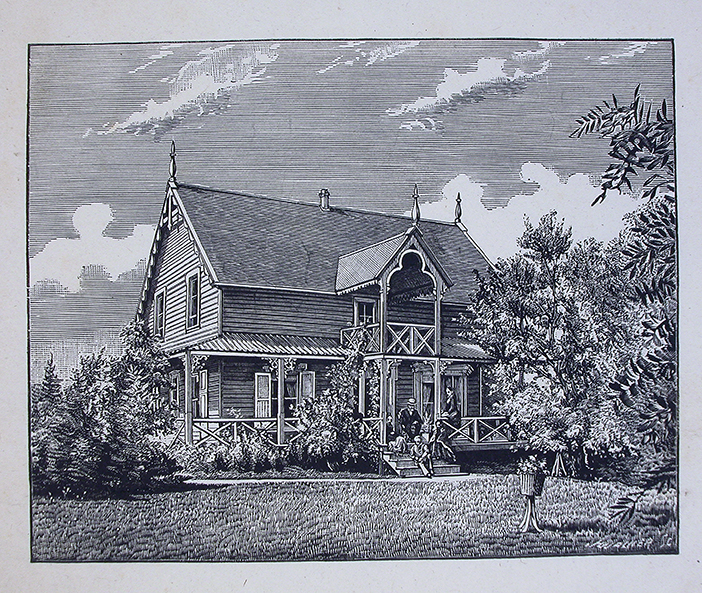

In the 19th century, Métis-sur-Mer was known as Little Métis. This English-speaking resort town owes a lot to Sir John William Dawson, an expert in the fossils and shells found on the Gaspé shore of the St. Lawrence River. Having adopted the village as a summer retreat for his family in the 1860s, he brought with him several professors from McGill University along with wealthy Montreal industrialists who helped fund the institution, like the Molsons, Refords and Redpaths, among others. By the end of the century, there were no less than 11 hotels to accommodate the tourists who would arrive by train or boat.

Nowadays, the houses and gardens overlooking the water, as well as the celebrated gardens Elsie Reford created at the mouth of the Mitis River in 1926, recall this golden age and enhance the town’s old-fashioned charm.

Anna Lois began going to Métis-sur-Mer as a teenager. In 1876, she and her husband began staying at Birkenshaw, her parents’ house, until 1883 when the couple and their children moved into a small neighbouring cottage. Both houses are typical of Métis-sur-Mer and are still inhabited by members of the Dawson Harrington family.

The surrounding area has many attractions, notably the unforgettable fragrance of wild rose bushes mixed with the salty scent of the river. Its microclimate is conducive to flourishing flower gardens. The beach is accessible and constantly renewed by the tides. The breathtaking view of the river, the sunsets and the incomparable wilderness nurture both thinking and feeling. Anna Lois painted this landscape many times, as well as the backcountry around Baie-des-Sables, the area’s many waterfalls and the islands of Bic. This stretch of coastline was her favourite place: it was where her family grew up and where she eventually died in 1917.

A WORTHWHILE DESTINATION

While one can view many watercolours by Anna Lois on the Museum’s Website, an exhibition at the Reford Gardens (also called the Jardins de Métis) offers a chance to see them in person and learn more about the artist’s history and personality. While curating this exhibition, entitled Light and Fog, I found that Anna Lois represented many women, now forgotten, who were heroines of everyday life and transmitters of culture. As an admirer of this work accomplished on the margins of domestic life, I wanted to situate it within a timeless artistic context. To this end, contemporary photographs by Ewa Monika Zebrowski, inspired by the very places that shaped the life of Anna Lois, hang side by side with the latter’s 19th-century watercolours.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Notes

- Between 1877 and 1893, Anna Lois gave birth to nine children, the first two of which died young. Edith died quickly from pneumonia at age 11, while Eric struggled with a variety of obscure illnesses before succumbing to tuberculosis at the age of 17. As it was an era of high infant mortality, Anna Lois constantly worried about her children’s health. See Annmarie Adams and Peter Gossage, “Health Matters: The Dawson and Harrington Families at Home,” Fontanus 12 (2010).

- Bernard J. Harrington was often away from Little Metis during the summer months, even in the early years of their marriage. Scientific research and preparing his classes at McGill University led him to travel across Canada, Europe and the United States, where he had earned his PhD from Yale University. Lois Sybil Winslow-Spragge transcribed and edited the letters her mother sent to her father from 1876 to 1907 in “Early Life at McGill Told by a Professor’s Wife” (1970), Dawson-Harrington Fonds, McGill University Archives, CA MUA MG 1022-5-001.

- Loren Lerner, “Anna Dawson Harrington’s Landscape Drawings and Letters: Interweaving the Visual and Textual Spaces of an Autobiography,” Material Culture Review / Revue de la culture matérielle 86 (2017): 70.

- Bernard J. Harrington’s salary was not enough to meet his family’s needs, so their material comfort depended on Anna Lois’ parents. See Annmarie Adams and Peter Gossage, “Health Matters,” and Lois Sybil Winslow-Spragge, “Early Life.”

- Letter from Anna Lois Dawson Harrington to Bernard J. Harrington, Little Metis, July 18, 1881, Dawson-Harrington Fonds, McGill University Archives, CA MUA MG 1022-5-017-0006.

- Letter from Anna Lois Dawson to Bernard J. Harrington, December 1875, Dawson-Harrington Fonds, McGill University Archives, CA MUA MG 1022-5-011-0007.

- Loren Lerner, “Anna Dawson Harrington’s Landscape Drawings,” p. 68.

- Letter from Anna Lois Dawson Harrington to Bernard J. Harrington, June 29, 1880, Dawson-Harrington Fonds, McGill University Archives, CA MUA MG 1022-5-016-0009.