Before there was Gore-Tex…

Read about the ingenious material that Indigenous communities used to make waterproof, breathable outerwear.

June 15, 2022

Today, when we think of waterproof yet breathable outerwear, we think of high-tech synthetic materials such as Gore-Tex. Before the invention of Gore-Tex, fabrics made from other synthetic materials such as nylon were used for their water-repelling properties.

Predating this, cotton was waxed or oiled and fabrics were rubberized. While these kept the wearer dry, they did not breathe, making it uncomfortable to wear these types of garments for any extended length of time, especially during periods of physical exertion.

Long before these materials were adapted for waterproof garments, northern communities used the intestinal membrane from marine mammals such as seals, whales and walruses. These garments were traditionally made in Indigenous communities located in the circumpolar North. In addition to being waterproof, they were lightweight—with some weighing as little as 85 grams—and were worn over regular warm clothing such as fur parkas.

They were primarily used by hunters to keep themselves dry when hunting from a kayak. However, more elaborate versions of these were occasionally used for various ceremonial purposes or for shamanic healing rituals. (Rowe, 1).

Our first encounter

I made the acquaintance of this parka when it arrived on my workbench. At first glance, it resembled a giant dusty potato chip, with a similar brittle, crispy texture.

Originating from a Yup’ik community, the parka consists of bands of intestinal membrane sewn together in a horizontal orientation. To protect against wind and water, there is no front opening, only a high neckline and a hood that can be gathered around the wearer’s face. The shoulders are quite roomy, to accommodate movement when hunting. A band of dehaired sealskin has been sewn around the hem, to provide some structure and stiffness to the bottom portion of the garment.

Preparing the membrane

The membrane is cleaned and processed to remove the outer and inner layers, leaving only a central layer. This layer has special properties perfectly suited to a waterproof garment—it is impermeable to moisture on one side, and wicks moisture out from the other.

Once the other layers are removed, the intestines are washed with saltwater or freshwater and then inflated like a long balloon and hung to dry. In preparation for sewing, the tubes are cut lengthwise to form flat bands. The properly prepared membrane has a beautiful, translucent appearance.

Waterproof seams

During construction of the parka, the membrane is oriented the same as it would have been in the animal, with the impermeable surface to the outside of the garment. This allows vapour to exit through the pores while keeping the wearer dry. (Issenman, 1997, 73).

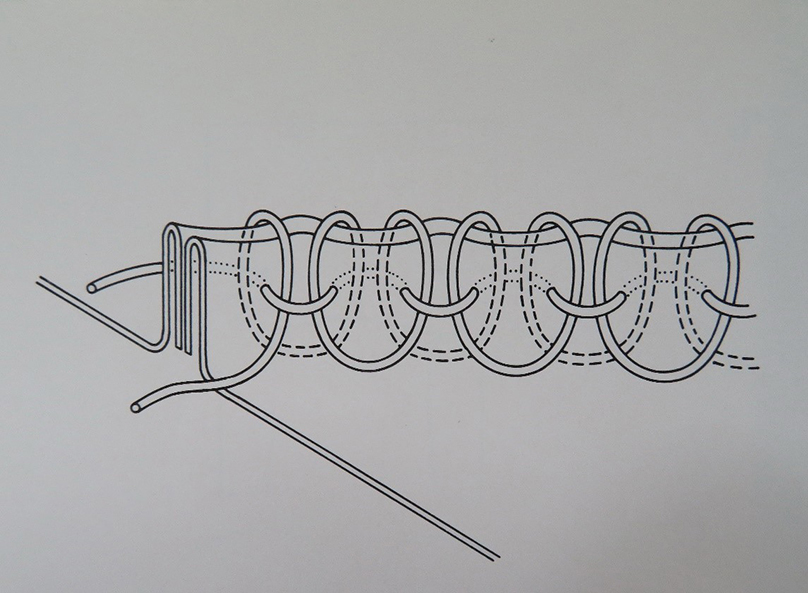

The bands of membrane have been sewn together using a type of waterproof stitch. For this, each side of the seam has been folded to the inside, creating four layers through which two rows of interlacing stitching have been sewn. Further to the functional aspect of the seam, the resultant stitch lends a decorative element to an otherwise unembellished garment.

Cleaning, reshaping and opening the parka

The first step in treating the parka was to clean as much of the surface as possible, and then reshape and open it. When wetted, the material regained the elastic, supple texture and translucency of the membrane. This was achieved through several sessions of humidification with water vapour and wetting with deionized water applied directly with a brush.

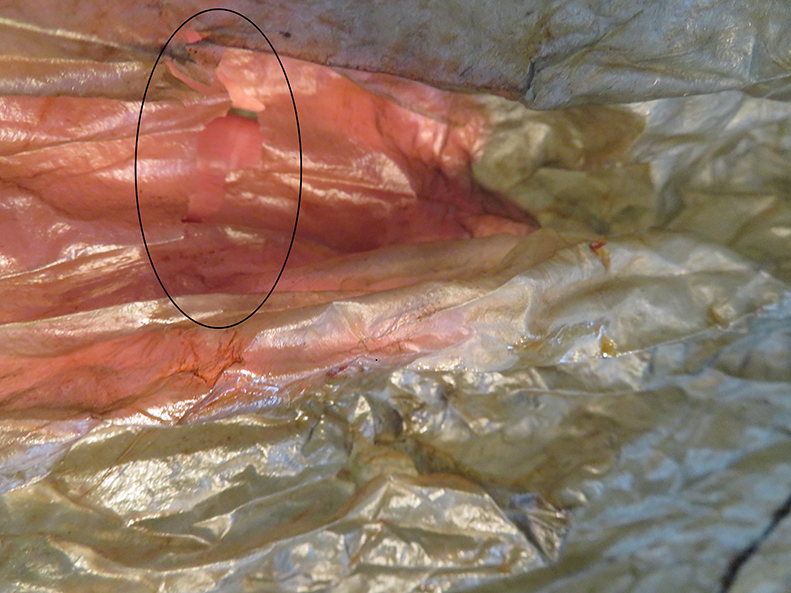

The reconstituted flexibility allowed me to gradually gain access to the interior and reshape the garment by padding it out with tissue paper. With the parka opened in this manner, extensive insect damage and tearing were now visible.

Adjacent to several of the tears along the bottom, large portions of the sealskin band were missing.

Mending the tears and the holes

Once the parka had been cleaned and reshaped, the tears and holes were mended. For repairs to the membrane, Goldbeater’s skin (the prepared outer membrane of an ox intestine commonly used in the production of gold leaf) was chosen as it provided a visually and texturally sympathetic repair. In preparation, the Goldbeater’s skin was toned with acrylic paints to integrate with the appearance of the membrane. Loss compensation for missing portions of the sealskin band incorporated folded strips of Japanese tissue prepared with watercolours.

Rice starch paste was used as the adhesive as it is non-toxic, water-based, and easily removed. The moisture in the adhesive quickly softened the membrane, making it easier to manipulate and align the sides of the tears, and helped with the placement of the fills.

The amazing properties of these parkas were essential to survival under certain northern conditions, and their construction required great skill. They were labour-intensive creations, not least during the steps required to properly clean and prepare the material.

In combination with the physical properties of the membrane, the waterproof stitching was crucial to the success of these garments at keeping the wearer dry. As a result, the seamstresses responsible for their creation were viewed with great reverence. There is a simple beauty to these parkas, and the combination of the translucency of the membrane, the workmanship, and their function made these highly prized garments.

References

Cruickshank, P and Sáiz Gómez, V. (2009). An early gut parka from the Arctic: Its past and current treatment. Prepared for the ICON-ethno workshop Scrapping gut and plucking feathers: the deterioration and conservation of feather and gut materials.

Issenman, B.K. (1997). Sinews of Survival: The Living Legacy of Inuit Clothing. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Issenman, B.K. (1988). Ivalu. Montreal: McCord Museum of Canadian History.

Reed, F. (2008). Embellishments of the Alaska Native Gut Parka. Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings.

Reed, F. (2005). “The Poor Man’s Raincoat: Alaskan Fish Skin Garments,” in Arctic Clothing of North America: Alaska, Canada, Greenland, ed. JCH King et al. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Rowe, S., Ravaioli, F., Tully, C. and Narvey, M. (2018). Conservation and Analysis on a Shoestring: Displaying Gut Parkas at the Polar Museum, Cambridge. Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies, 16(1), 1-11.