Between space and mass

Ludovic Boney discusses Trade Ornament, his piece featured in the permanent exhibition Indigenous Voices of Today.

October 27, 2021

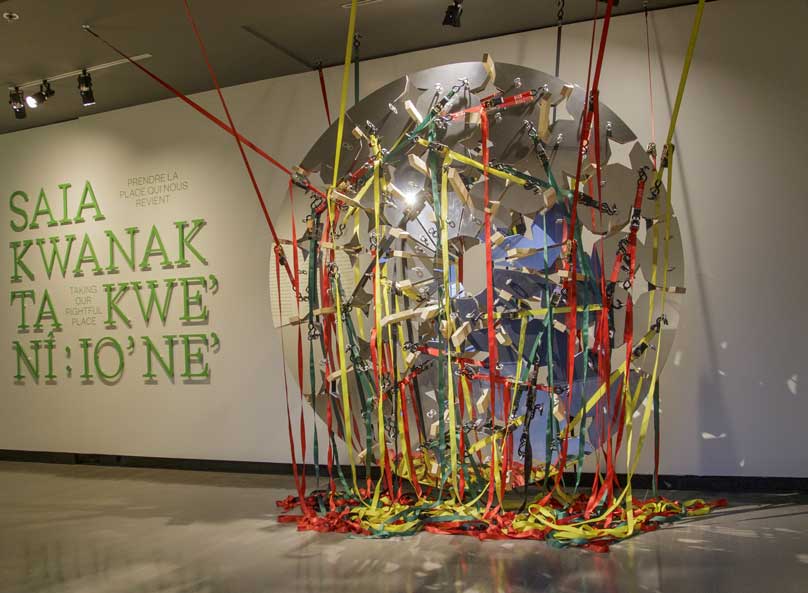

An enormous disk of polished aluminium hangs vertically from the ceiling on brightly coloured straps. Taking a closer look, I see that it is made of numerous fragments of metal bound together using only pieces of wood and straps, no solder or screws. The immense two-sided circle is pierced with diamond-shaped holes that bring light in to reveal the empty space within the work. There is an extraordinary balance between the massive size of the sculpture and its striking fragility.

Both imposing and ethereal, intimidating and delicate, Trade Ornament is a work by Ludovic Boney, a Huron-Wendat artist invited by the Museum to create an installation for the new permanent exhibition Indigenous Voices of Today: Knowledge, Trauma, Resilience.

After studying at the Maison des métiers d’arts de Québec in Quebec City, Ludovic Boney founded a studio in the city’s Limoilou neighbourhood with four other artists. The recipient of numerous public art commissions, he quickly established both his style and reputation.

Seated at a table on Victoria Street, Ludovic tells me about his work and his approach. Wearing a t-shirt and shorts, he has a sincere, penetrating gaze.

Unlike most artists, I do more public art than exhibitions. I have always been interested in making large-scale works in public spaces for everyday people. I enjoy creating surprises.

What I actually do is create shapes. He goes on to explain that although he looks for a technical challenge, the most important element is to ensure that the observer has an aesthetic experience. In other words, the work tells its story through the senses. Sight, sound and even touch, if possible. When I tell him about my impression of his work, he nods with a little smile. I explored the work as if I were exploring a landscape. When you gaze at a panorama, you also open yourself to the sensation of its beauty and the loss of equilibrium triggered by its vastness. That is the essence of an aesthetic experience: a pleasure for the senses and the discovery of an inner landscape that mirrors the one outside.

Although the shape of the work clearly evokes a trade ornament and the tie-down straps recall the colourful ribbons used on traditional clothing, he notes that the work as a whole is more about feeling than meaning.

By bringing together seemingly disparate materials left over from previous projects, the work echoes the silver medallions and brooches the British crown would present to its Indigenous allies. Worn notably by Huron-Wendat chiefs, these ornaments were powerful cultural symbols.

I look at his large hands lying flat on the table—the hands of a sculptor. Broad and calloused, they are capable not only of pounding steel but of treating it with delicacy.

I think again of Trade Ornament, rising majestically, suspended in the very heart of the exhibition. Those very hands shaped several kilos of wood, metal and synthetic fabric straps in a studio and assembled them at the McCord Stewart Museum to evoke a subtle connection between contemporary art and a bygone cultural and artistic practice. All this so that curious observers could discover a dynamic balance between warm and cold, space and mass, the mundane and the symbolic, the contemporary and the traditional.