Costume Balls in the Museum’s Collections

The McCord Stewart Museum holds an abundance of mementoes from costume balls. Why were they saved for generations?

November 22, 2024

Assembled over the past century, the McCord Stewart Museum’s vast collections are an extraordinary trove of visual, material and print culture. Conspicuously overrepresented within this historical record are images, garments, documents, ephemera and other objects that bear witness to lavish costume balls and skating carnivals held in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

While their sheer abundance points to the outsized impact of these events on people’s lives, against the backdrop of most other remnants of life in the same period their joyful exuberance is startling. The efforts put into immortalizing costumed events belie their seemingly ephemeral nature. Why was there such a degree of investment in these momentary transformations of the self?

The beginnings

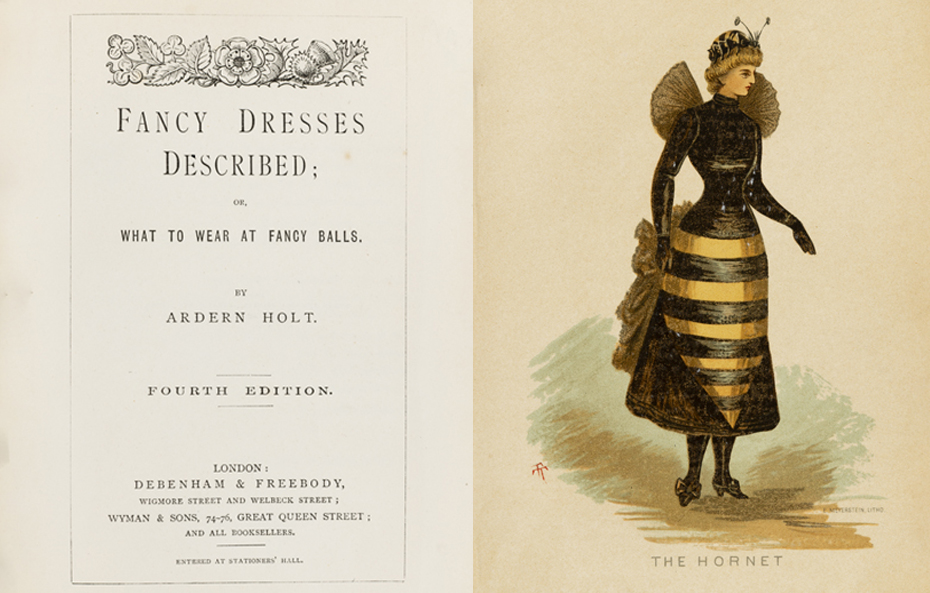

My journey researching the topic of fancy dress balls, as they were often called in their own time, began long before I joined the McCord Stewart Museum in 1998 as Curator, Costume and Textiles. The topic for my master’s thesis grew out of my fascination with the 1887 edition of a small volume Fancy Dresses Described; or, What to Wear at Fancy Balls intended to inspire ballgoers with ideas for characters and costumes.

My study looked at four large society balls held in the last quarter of the nineteenth century in the Canadian cities of Ottawa, Toronto, and Montreal, all with the involvement of Governors General, and each with its own distinct political intent.

These balls were commemorated in large-scale composite and flash photographs, photograph albums, and souvenir books of group photographs and artists’ renderings. Furthermore, all received extensive coverage in society pages well beyond the cities where they were held. There was no shortage of primary source material to help reconstruct these most prestigious and memorable of society entertainments.

Skating Carnival, 1870

My research of course brought me to the McCord Stewart Museum, where the oversized painted photograph of the 1870 skating carnival—one of the most exhibited and published pieces in the collections—stands as arguably the most flamboyant Canadian example of commemorating this genre of entertainment.

However, the negatives from which 150 individual portrait photographs were cut and pasted to create this composite represent a mere fraction of the Photography collection’s images of people dressed in costume for social gatherings.

In the myriad albums of small prints that William Notman’s studio in Montreal kept as chronological indexes of its glass negatives, clusters of images depicting people in fanciful costume, all taken within the same few days or weeks, were signposts of the events that had marked the social calendars of the year, and sometimes even the decade and generation.

Could some of these costume ball outfits still exist?

The abundance of visual and textual sources stirred my abiding interest in the material culture of fancy dress, i.e. extant ball costumes. Extensive searches through museum and private collections initially turned up very little. The survival of any article of clothing for a century or more is always a fortunate accident that defies all odds, and those that do survive tend to be pieces that their owners considered most special or valuable during their lifetimes.

Compounding this generalized rarity of historic dress, fancy dress falls outside the collecting mandate of most institutions, which was the case at the McCord Stewart Museum at the time. When I did locate examples in collections, they were often catalogued as something else. Fancy dress ensembles may have been packed away in trunks by their owners because of fond associations or the hope of opportunities for future use, but they were most often misidentified by later generations.

After a few serendipitous discoveries, I was able to refine my approach by searching for garments that stood out for their puzzling styling or odd attributions. With my assemblage of well over 1000 images from these four events, on several occasions I was able to determine who wore them and to what event.

To my surprise, the wellspring of extant objects with past connections to the practice of fancy dress balls has not run dry. Inquiries to descendants of ball-goers have uncovered more photographs and garments, showing how families valued them as keepsakes.

Close examination of more unattributed garments has yielded up clues that eventually brought to light their appearance at one of these balls and, on occasion, their photographs. For instance, it is now clear that this phenomenon continued well into the twentieth century.

Discovering new material

The exhibition Costume Balls: Dressing Up History, 1870-1927 encompasses, for the first time, a large historical ball that was the social event of its generation in 1927. Scrutinizing photographs has led to the discovery of still more items with a history of use in fancy dress, including portrait miniatures and further Indigenous objects that were incorporated into costumes.

Rereading society pages has revealed more instances of descendants wearing heirlooms as fancy dress, which have been matched to extant garments not previously known to have this history.

Donors have come forward with unexpected gems, including another painting of the aforementioned 1870 skating carnival and a piece of sheet music that instructed ball guests in historical dances in the 1890s. Pieces of the puzzle continue to reveal themselves, complicating and enriching an ever-expanding picture and heightening the imperative to bring it out of the margins.

Interconnected garments and images

The exhibition aims, among other things, to shed light on why these many objects and images survived as they did, along with their mutual interconnectedness, as improbable as it is significant.

A collaborative effort involving many colleagues within the institution, the exhibition foregrounds the range of our multiple fields of expertise. Our cross-disciplinary access to this historical record shapes our understanding of the material and ideas that we work with most closely. Our viewpoints have broadened as we juxtapose historical objects and archival images to show how each serves the understanding of the other.

In bringing to the foreground the visual and material legacy of costume balls, we hope to demonstrate that it is not just evidence of participants’ deep engagement in the experience, but an intrinsic element.

—

The full version of this essay was published in Costume Balls: Dressing Up History, 1870–1927, edited by Cynthia Cooper.