The diplomacy of transatlantic Christian wampum

Religion and politics are woven into these multimedia, multicultural, multilingual objects.

November 28, 2023

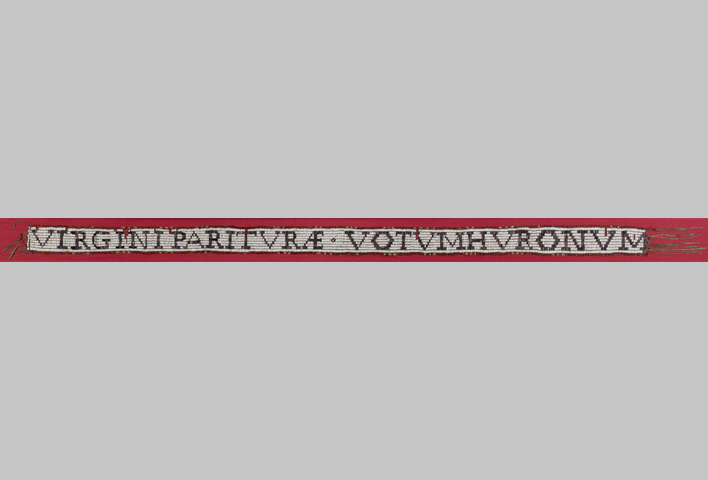

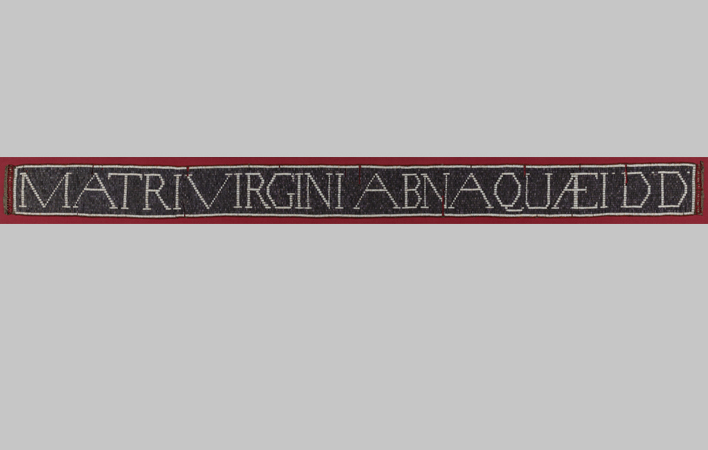

The exhibition Wampum: Beads of Diplomacy presents four wampum belts—three bearing Latin script—that were sent to Catholic shrines in France and Italy some time in the 17th to 19th centuries. They are the only remaining transatlantic Christian wampum among the ten or so recorded in historical documents. This is the first time that some of them have returned to North America.

Wampum belts embodying both tradition and innovation

In the context of the wampum diplomacy practised at that time in North America, these belts were groundbreaking: designed to travel, they were sent without an Indigenous interpreter to convey, in person, the words they contained. Instead, Indigenous communities embedded their message by weaving the beads into letters and meaningful symbols that could be interpreted by the religious communities to whom they were destined.

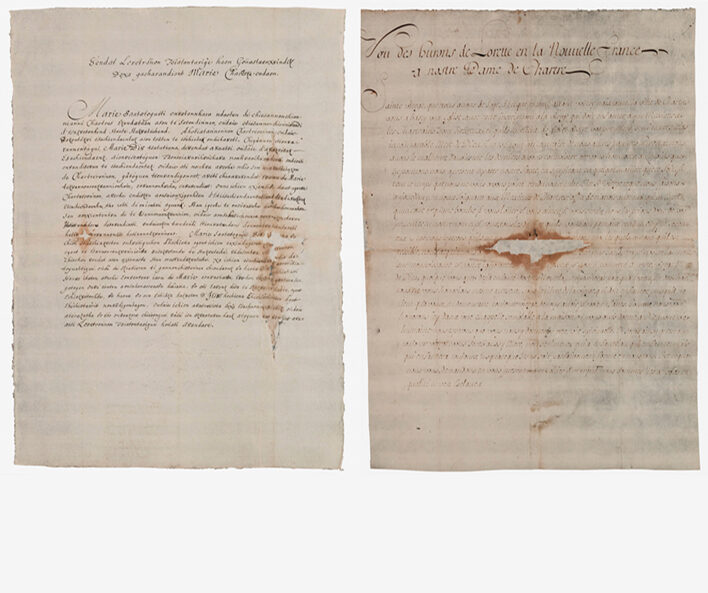

Furthermore, these belts were always accompanied by a letter written in an Indigenous language, along with a French or Latin translation, to provide crucial information regarding the intentions of the Indigenous people who had made and sent them.

From a European perspective, the words woven in shell beads and recorded on paper can perhaps be easily construed as ordinary expressions of Catholic devotion. However, it is important to relocate them in the context of Indigenous diplomacy, which communicates using metaphors, notably those relating to kinship. One must pay special attention to the coexisting Christian images and Indigenous references to properly understand the role of these belts created to navigate between cultures, languages, communities and time periods.

Objects that are, first and foremost, Indigenous

Documentary sources show that Indigenous peoples played an active role in religious diplomacy. The first Christian wampum given by the Huron-Wendat of the Marian congregation on Ile d’Orléans to the professed house of the Jesuits of Paris in 1654 was made after the community as a whole gradually built up a store of wampum beads, a practice common in 17th century Iroquoian villages.

Period sources also specify that Indigenous community members, not the Jesuits, wove these beads into belts. With regard to the Abenaki wampum sent in 1684 to the tomb of St. François de Sales, in Annecy, France, three Abenaki women were named as having helped create the belt: Ursule, who provided hundreds of beads, “Tall Jeanne, who made the whole Collar [sic], and Colette, who set the porcupine quills in it.” The decorative border of porcupine quills was similar to that of the Abenaki wampum sent to the Virgin of Chartres in 1699, which can be seen in the exhibition.

These objects were therefore not made by missionaries. Instead, they were the result of a long process of pooling resources and expertise, a process in which Indigenous women played a key role.

Words formulated by political councils

The messages conveyed by these wampum were also the outcome of collective deliberations held in Indigenous villages. The 1654 letter sent by the Huron-Wendat said: “We assembled, and we said,” while the letter from 1673 that accompanied a wampum sent to the Virgin Mary in Loreto, Italy, indicated: “We have all decided together, reaching a general consensus, to make you a belt and inscribe it with your own words.“ In 1684, missionary Jacques Bigot (1651-1711) noted that he had to wait until the men returned to the village so the wampum belt destined to St. François de Sales could receive its message.

The letters accompanying these wampum were sometimes signed by orators and chiefs. In 1654, Jacques Oachonk, Louys Taieron and Joseph Sondouskon were identified as the Huron-Wendat authors of the speech. In 1831, Algonquin Grand Chief Pierre-Louis Constant Pinesi, Nipissing Chief François Papino, Jean Baptiste Kikons and Simon Cha8anasiketch all signed the speech addressed to Pope Gregory XVI that accompanied a wampum measuring over two metres in length.

The process of creating transatlantic Christian wampum followed protocols similar to those for traditional diplomatic wampum: each belt represented the desires of a community that had publicly weighed and discussed its message.

Faithful translations?

Although Indigenous creators wove the wampum and gave them a message, European missionaries were the ones to translate these speeches and act as intermediaries to explain the meaning of these gifts. Unlike diplomatic missions where words were translated simultaneously, these texts could be slowly translated and interpreted because the missionaries could discuss their meaning with those who had written them and the Indigenous language teachers who lived in the same villages. A preliminary version of the French translation that accompanied the Algonquin speech sent with the wampum in 1831 demonstrates that these translations were well thought-out and revised. That being said, contemporary Indigenous language experts can help reveal the liberties that the missionaries sometimes took with regard to the original text.

Generally speaking, the tone and level of language have been adapted to fit the communication standards of the time. These letters were addressed to both a Catholic saint and the community that cared for his or her shrine. For the exchange to be effective, the missionaries made sure that the French version of the message showed respect and humility. In Europe, those working at the shrines often jumped to the conclusion that these performances were evidence of conquest. For example, in 1700 the assembly of the Chapter in Chartres published the letters send by the Huron-Wendat and Abenaki with the wampum, presenting them as a sign of “submission” to the Virgin and the cathedral.

Religious diplomacy in a Catholic and Indigenous context

To properly understand these intercultural objects, one must consider the metaphor of kinship in both its Christian implications and in the context of traditional Indigenous wampum diplomacy. For example, when sending a wampum in 1654, the Huron-Wendat asked to be recognized as “children of Mary.” This designation represents potential kinship with powerful European groups: “We are brothers, because the mother of Jesus is our mother, as well as yours.” In Indigenous diplomacy in northeastern North America, the term brothers refers to the idea of equal allies as well as the concepts of mutual support and military and economic solidarity. Through this wampum, Europe was subjected to the logic of an Iroquoian clan system.

Some years later, when the Huron-Wendat founded the village of Lorette in 1673, they offered wampum to St. Michael, St. Anne and the Virgin Mary in Loreto, Italy. The belt sent to the Virgin Mary, which can no longer be found, is described as bearing the words that Mary addressed to the angel who told her she would be a mother. Mary had already agreed to be the mother of the Huron-Wendat in 1654, but with this wampum, like an Iroquoian clan mother, she was giving them land. As the Huron-Wendat said in their letter, they were entering into the “domain” of Mary and recognizing her as their “queen”. In other words, they addressed her as a figure with ancestral authority over land associated with kinship systems.

Despite the language of European feudalism, we must not underestimate the Iroquoian political sophistication of the Christian Huron-Wendat. While these wampum belts and their accompanying speeches were addressed to a European spiritual audience (saints, the Virgin), they were also addressed to a local audience, and had an impact primarily in North America. Devotion and diplomacy, religion and politics were thus inextricably entwined in these polysemic objects, which engaged with multiple recipients at a time, in several languages.

Today, as some of the oldest known examples of wampum, thanks to their precise dating, these belts convey a message that transcends generations. Their woven patterns and longevity are symbols of the tangible, emotional connection between Indigenous and European communities, between the past and the present. Perhaps these objects still have a role to play in contemporary diplomacy between Indigenous peoples and the Catholic Church, notably with regard to the traumas experienced since the 17th century. Their presence in Montreal may help the parties involved continue the dialogue.