Discovering Duncan

Discover this artist active in Montreal during half of the 19th century and who immortalized some of the most eloquent views of the city.

September 5, 2023

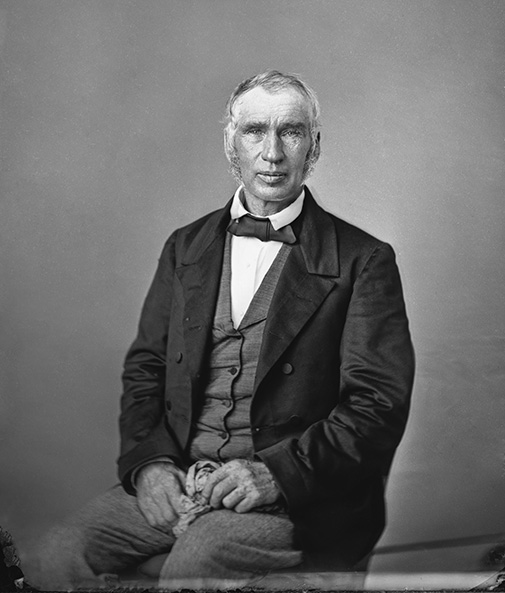

Two photographs from 1863 show artist James Duncan to be a tall man with pleasant features, clear eyes, and full lips showing a hint of a smile. We know nothing about his social background. Born in 1806 in Coleraine, Northern Ireland, he may have grown up in a home that encouraged the arts. According to his daughter Jane, he had carefully preserved a sketchbook of nature drawings done when he was eight.1

Duncan’s reasons for emigrating to the British colony of Canada are unknown. Perhaps the financial crisis of 1825, food shortages and crop failures in Ireland encouraged the young man to seek his fortune abroad. Duncan was the first British artist to settle permanently in Montreal in 1830. He truly put down roots in 1834 after marrying Caroline Benedict Power (1808–1877), a native of Sorel. The couple went on to have four boys and three girls.

Public records from 1842 to 1879 indicate that Duncan lived on either Champ de Mars Street or St. Louis Street, between Sanguinet (a section now known as Gosford Street) and Bonsecours. In 1858–1859, he also rented a studio at 126 Notre-Dame Street.

Though he did not lead a lavish lifestyle, Duncan did own some property, according to the inventory of his estate2. His two-storey home in Longueuil was comfortably furnished, with a minimum of decoration. Despite containing a sizeable number of works, his estate did not include any art supplies, suggesting that the 75-year-old artist was no longer painting.

ONE OF QUEBEC’S MOST FAMOUS UNKNOWN ARTISTS

Today, few people are familiar with the name James Duncan. And yet, a number of his works are actually very well known and help make up the public’s impression of 19th-century Montreal. Why has Duncan’s personal renown faded from our collective memory, while that of his work has persisted? The primary reason is the popular perception of his work following his death. His pictures no longer represented reality, while illustrations and photography provided a contemporary and increasingly accurate image of the growing city.

| Explore James Duncan’s works on the Online Collections |

Duncan’s watercolours were preserved and appreciated as illustrations, as documents that helped interpret the changes occurring in Montreal’s cityscape. They were valued by archive centres and history museums rather than art museums, which are more likely to identify a work with the name of its creator.

Recognized more for their subject matter than their artistic quality, Duncan’s watercolours did not always feature the artist’s signature. In countless articles illustrated with reproductions of his art, no mention is made of his name.

Thanks to connoisseurs of his work like Jacques Viger, Anthelme Verreau, David Ross McCord, William Hugh Coverdale, Sigmund Samuel and Peter S. Winkworth, Duncan’s works were preserved and added to public collections.

As Christian Vachon, Head, Collections Management and Curator, Documentary Art suggests, Duncan was an early photojournalist. His proximity to public events gave his work authenticity and the ring of truth. However, focussing on the subjects he painted is not meant to minimize his work.

A WELL-BALANCED PICTURE OF MONTREAL

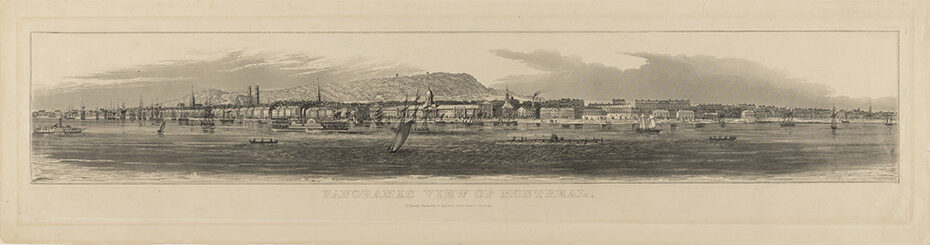

In his panoramic views, he would paint the city in a small size. Duncan’s art was to create this condensed perspective—a replica of the city so small that it could be seen all at once, enabling viewers to instantly recognize and appropriate it. He was able to do this by meticulously rendering and embedding a wealth of details.

Duncan helped create a well-balanced picture of Montreal. Recognizing what defined the city and its unique lifestyle imposed by winter, he recorded the leisure pursuits of the middle and upper classes, where those of different social strata co-existed without interacting. Though focussed primarily on men and the characteristics of courage, honesty and endurance, his scenes also feature women and Indigenous people. As a reporter, Duncan chose the angle from which he approached his subjects. As an artist, he used drawing, colour, form, and clarity to masterfully portray his subjects and enchant the viewer.

THE 1830s: BECOMING ESTABLISHED

Duncan’s views of Montreal became his trademark. Instead of presenting himself as a painter of portraits, the genre most likely to attract commissions, Duncan used this exhibition to introduce himself as a landscape artist. Duncan’s landscape was in the tradition of others created earlier. As seen from the plateau of Mount Royal on a clear fall day, the view of Montreal includes the Monteregian Hills, St. Helen’s Island, and the city skyline in the middle ground.

His desire to find original viewpoints is evident in compositions that revisit the same subject, but from a different angle and perspective. Though he constantly returns to the same urban scenes, he creates multiple variations that elicit surprise by revealing a formerly unseen aspect. Though the downtown area was long a popular subject with him, he also became interested in the communities developing along the river and to the north.

LANDSCAPES OUTSIDE MONTREAL

In his efforts to update his approach and the iconography of Montreal, Duncan chose a variety of viewpoints from which to paint. He often travelled west to capture views of the city from Trafalgar or Côte des Rolland. He would then travel on to Lachine, where he would make the windmill the focal point of his observation.

A regular visitor to St. Helen’s Island, he would cross the river to go to Kahnawà:ke, La Prairie, St. Lambert and Longueuil.

Montreal becomes a focal point when seen from the south shore, and several of Duncan’s views show the city from St. Lambert, with its bucolic foreground of cows grazing in the fields.

THE 1870s: GRADUAL DISAPPEARANCE

St. Helen’s Island provided the setting for the artist’s last known works, created in 1878 when the island became a public park following the garrison’s departure.

James Duncan retired to Longueuil (240 St. Charles Street), where he lived with his son David Logan. He died September 28, 1881.

In the following decades, none of Duncan’s work appeared in any exhibitions or on the art market. Consequently, the name of an artist active in the Montreal art world for 50 years, an artist who had immortalized some of the most eloquent and animated views of the city, gradually disappeared. His work, however, was preserved by history lovers wishing to safeguard visual evidence of 19th-century Montreal.

An avid follower of the latest developments marking his adopted city, Duncan celebrated and documented Montreal’s evolution for approximately 50 years.

The full version of this essay was published in James Duncan (1806-1881) – Painter of Montreal, edited by Suzanne Sauvage and Laurier Lacroix

NOTES

- Letter from Jane Duncan to David Ross McCord, July 20, 1906, P001/5023, McCord Stewart Museum (MSM) Archives, Montreal

- The post-death inventory compiled by notary John O’Hara Baynes (Baynes registry, BAnQ Vieux-Montréal, legal document 6120, December 3 and 20, 1881) listed a collection of 116 watercolours in various sizes, framed and unframed, evaluated at between $1.00 and $25.00, along with 7 oil paintings. He left assets worth a total of $784.55 and a bank account with $622.19.