Discovering Edward Mitchell

Who was Edward Mitchell, Dartmouth College’s first Black graduate and a Baptist minister in Lower Canada?

February 20, 2023

Documenting the collections is not merely the domain of the Museum’s team. Rather, the daily contribution of members of the public, donors, and researchers is essential in helping us understand the objects and documents in our care. The Mitchell Family fonds is notable in this regard as, for several decades, the Museum has been preserving the archives of Edward Mitchell (1792-1872), a Baptist pastor in the Eastern Townships from the 1830s through to his death. However, it was only recently that a group of American and Canadian researchers revealed that Mitchell was born in Martinique, and was one of the first Black men to receive a university education in North America, in his case, at Dartmouth College. One of his two biographers, Professor Forrester Lee, provides a glimpse into Mitchell’s extraordinary life.

Mathieu Lapointe, Curator, Archives

—–

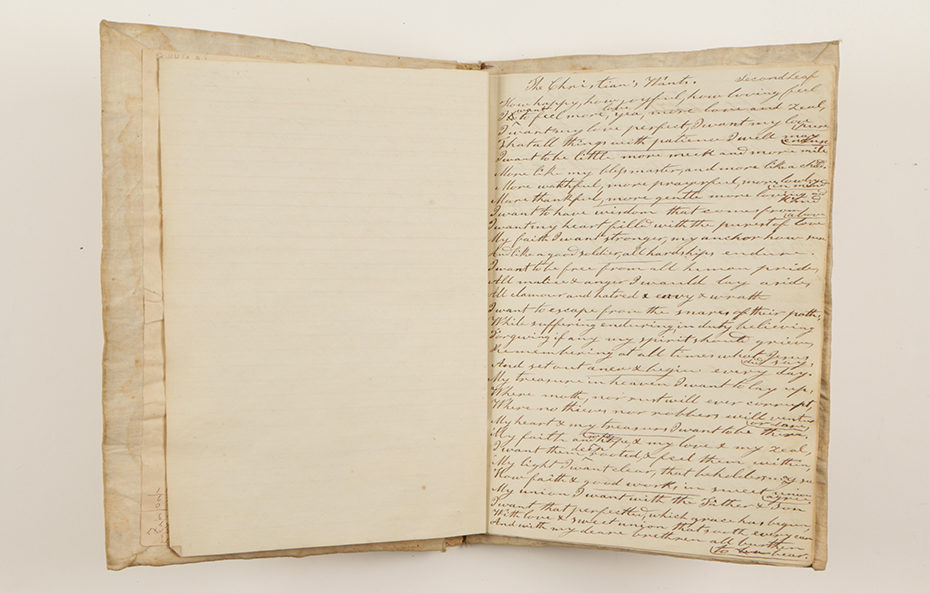

More than a half-century ago, the McCord Stewart Museum of Montreal received from a member of the Mitchell family of Canada and New England some hand-written documents dating to the early 19th century. Among the items were the personal papers of Rev. Edward Mitchell, only the fourth man of African descent to graduate from a North American college, and the first to graduate, in 1828, from Dartmouth College or, for that matter, from any of the schools known today as Ivy League.

Not until the late 1990s were these preserved documents discovered by Dartmouth and Canadian researchers, who immediately recognized their significance.1 Previously, the few second-hand accounts of Mitchell’s life had offered scant details of his transnational journey across the slave-bound 19th-century Atlantic World, from Martinique to New England and Lower Canada as an ordained Calvinist Baptist minister.

The Mitchell Family fonds held at the McCord Stewart Museum provided a trove of Mitchell’s college compositions, letters, religious sermons, and a personal biographical sketch containing rich details of the life of a man of color in the Atlantic World.

FROM MARTINIQUE TO MAINE

Born in Saint-Pierre, Martinique, on January 23rd, 1792, Mitchell was the mulatto son of a “Frenchman” and a “native of the island,” as he put it when asked. His early years spanned a turbulent period of rivalry among world powers—notably France and Great Britain—seeking dominion over cash-rich Caribbean sugar colonies.

In 1809, at age 18, Mitchell left Martinique as a crew member aboard the brig Tropic with Captain William Prentiss, a prominent seafaring merchant based in Portland, Maine. Mitchell lived with the Prentiss family for two years while pursuing his ambition to become a mariner. Then, on a voyage along the Eastern seaboard, a sudden storm arose, and Mitchell very nearly perished. Honoring his promise to serve the Lord if he was saved, Mitchell embarked on the first step in a life of Christian service.

Seeking religious guidance, Mitchell traveled from Maine to Philadelphia in 1811, and joined a Baptist congregation. He sought to find his place among people of color in Philadelphia, where the Black community had already embarked on its long journey to progress. He was baptized by William Staughton, a charismatic, White Baptist evangelist who Mitchell credited with guiding his religious conversion.

His first marriage was to a woman of color, likely of Haitian origin, and he settled his family among other Black Caribbeans and Americans. While in Philadelphia, he broke bread with the city’s most prominent Black religious and civic leaders. But after the deaths of his first wife and children, he was persuaded to relocate by an offer of employment from the president of Dartmouth and the promising reward of a college education.

ADMITTED TO DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

He left Philadelphia in 1820 with Dartmouth President Francis Brown, who required assistance returning to the New Hampshire college via horse and buggy. At Dartmouth, Mitchell gained a new footing in the world of educated and informed men of progressive moral bent and humble means.

| To learn more on Edward Mitchell and his time at Darmouth College visit the virtual exhibtion Finding Community: The Life of Edward Mitchell 1828 |

Edward Mitchell applied to Dartmouth four years later but was initially rebuffed by Dartmouth’s trustees, who claimed not to want to “offend” students. Upon learning of the trustees’ decision, the students convened and collectively submitted a letter of protest:

“From what we know of Mr. Mitchell’s moral character and intellectual attainment we wish him every success; and, far from feeling any disrespect towards him on account of his color or extraction, we think him entitled to the highest praise…we will cheerfully receive him as a companion and fellow student.2

The trustees reversed their decision and Mitchell graduated four years later, in 1828, along with forty classmates.

FROM NEW ENGLAND TO THE TOWNSHIPS OF LOWER CANADA

Religiously grounded and ever-hopeful, in the tradition of a Baptist evangelist, Mitchell began a northerly journey that converged on the rural villages of Lower Canada. The Baptist Home Mission Society would later report that by 1842, “he had traveled by foot, horse, and sleigh 16,646 miles, preached 2,207 times, and baptized 103 persons,” a testament to his “indefatigable exertions.”3

In 1837 he was called to the pulpit of the Stanstead-Hatley Calvinist Baptist Church, where he would remain for the next 34 years. Mitchell’s congregation met initially in Georgeville’s brick “academy” building, but it burned down in 1848 and was rebuilt. It was known as the “red schoolhouse,” and it still stands today in the village center.

Mitchell and his wife, Ruth O. Cheney, whom he married in 1832, settled in Georgeville on Lake Memphremagog, where they raised a family of three children. A place of picturesque beauty, the village was immortalized by artists and photographers such as William Henry Bartlett, William Notman, and Alexander Henderson. The family’s 280-acre farm included several barns, livestock, fields of wheat and barley, fruits and vegetables, along with honey and maple syrup that surely sweetened Mitchell’s days in his final years.

SILENCE ON THE MOST PRESSING ISSUE

Slavery had been abolished in the British colonies in 1833, the same year Mitchell established permanent residence. Although his papers document his scholastic achievements, spiritual transformation, and tireless religious service, there is virtually no mention of his encounters with racism in America, even though he was confronted with acts of bigotry and intolerance. His essays, sermons, and letters are silent on the most pressing social and moral issue of the day.

Only after reviewing Mitchell’s papers at the McCord Stewart Museum were we able to fully grasp how unusual and, ultimately, understandable his life’s journey was. No man of color had previously traveled across the Atlantic World, from the French Caribbean to the tenuous life of a low-wage porter in Philadelphia, America’s vibrant center of political and social discourse, then to relative seclusion in northern New England and Lower Canada. Yet, he was far from invisible in the whiteness of northern New England.

From Dartmouth sources, we read of nothing but contexts, incidents, and identities connected to race, ethnicity, and birthplace. Even as Mitchell left the United States for Canada, American observers, news editors, memoirists, and historians continued to view and discuss him in a racial context. Once on the path of religious salvation, he was encouraged to put his rhetorical and evangelical talent to use, and he had no interest in reliving the taunts and insults of his days in Philadelphia or his initial rejection by the Dartmouth trustees.

We came to better understand Mitchell as a free man of color traversing the Atlantic World in different contexts of racial oppression and resistance. During his formative years in the French Antilles, he was witness to a simmering cauldron of protest and rebellion by free Blacks and enslaved Africans. In the United States, he would learn of short-lived rebellions by enslaved workers on southern plantations, and the early signs of organized protest among free people of color. American Blacks were building self-governing religious, social, and educational organizations within increasingly segregated communities. Over time, such actions would lead to the expression of a distinct identity, self-consciousness, and culture among American and Caribbean peoples of African ancestry. These developments gained momentum in the years after Mitchell had settled in Canada.

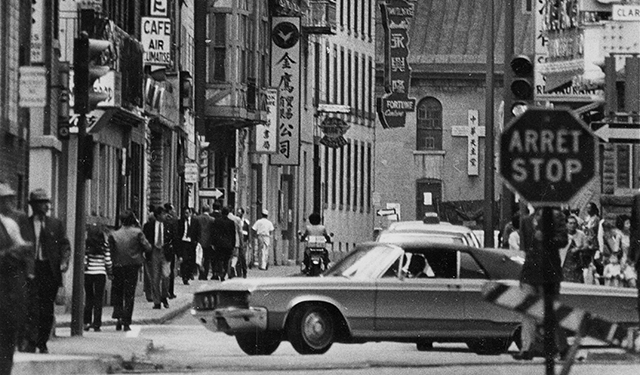

Mitchell assimilated into the Anglo-French-Caucasian world of the Eastern Townships of rural Quebec. He found acceptance in small villages first populated by Anglo-Americans and later by Irish and Scottish immigrants, then French-Canadian colonists, but no Black families. Like other settlers, he was foremost an immigrant, with Baptist religious and family associations entirely familiar to his community. Race, as we know and understand it today, had ceased to matter for Edward Mitchell. The slavery that concerned Mitchell was slavery to sin, from which the White residents of Lower Canada were, in his view, in need of deliverance. And no matter how earnestly we attempt to understand this Caribbean man of White and Black ancestry, detached from his cultural roots and imperfectly planted on American and Canadian soil, our understanding and conclusions remain equally imperfect.

An immigrant from a Caribbean French slave colony, Mitchell had traversed the Atlantic World and lived in various contexts of racial oppression. Yet, he skillfully navigated the racial biases and negative presumptions he encountered, and forced Dartmouth College to stand up against racial exclusion in higher education. At Mitchell’s death in 1872 at the age of 80, the editor of the Stanstead Journal extolled him as “a man of steadfast integrity; a preacher of marked ability; and a scholar. In the very last years of his life you would find him reading the Bible in the original languages. He has gone to receive his crown.” Baptist colleagues deemed Mitchell to have been “the most profound theologian ever settled” in Lower Canada.4

NOTES

1. John Scott (1930–2018), when president of the Georgeville Historical Society, and Professor Catherine Desbarats, Chair of History at McGill University, both shared valuable research notes and insights with Dartmouth researchers.

2. Dartmouth College student protest letter. https://exhibits.library.dartmouth.edu/s/mitchell/page/admitted

3. Forrester A. Lee, & James S. Pringle, A Noble and Independent Course: The Life of the Reverend Edward Mitchell, Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press, 2018, p. 120.

4. William Cathcart, The Baptist Encyclopædia, Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1881, vol. 2, p. 808.