Embellishing birchbark: All bark, and some bite

See how paper birch trees were used to create objects embellished with various Indigenous art forms.

May 26, 2022

The paper birch tree is known for its distinctive white appearance and peeling papery bark. Although famously used to make birchbark canoes, the bark is also used for other objects and can be embellished with the Indigenous art forms of bark scraping and biting.

It starts with the tree itself, whose scientific name is Betula papyrifera, which grows across much of Canada. All parts of the tree are useful—the wood is used for tools and furniture, the sap is made into syrup, and the bark helps make things like containers, canoes, medicine, and kindling.

Birchbark

The bark of the paper birch is particularly white and easily peels into thin layers. As the tree grows, the spring and summer layers of bark have large cells with high concentrations of the natural compound betulin—a white crystalline substance that imparts a natural resistance to mould, fungus, and insects, while giving the bark its white colour.

In the other seasons, bark cells are smaller and contain higher concentrations of tannins and phenolic compounds, giving winter bark a darker reddish colour compared to lighter spring bark. As a result, the bark has distinct alternating light and dark layers that easily separate.

Additionally, birchbark contains a high concentration of suberin, another natural compound that imparts flexibility and water resistance. This makes birchbark useful for making containers—well-constructed birchbark vessels are waterproof and can be used as cooking vessels and, of course, canoes. The preservative properties of betulin also make birchbark receptacles useful for food storage.

Birchbark can be harvested from living or dead trees, at any time, but this is best done in spring when the sap is flowing and the bark is flexible. Younger trees also produce thinner bark that is easier to work with in certain applications, such as biting.

The white outer surface of the bark is called the paper side, and the inner reddish-orange surface is called the cambium side. Bark cut and peeled from a tree naturally curls with the paper side inward, so objects made from bark, such as containers, are constructed with the cambium side out, following this natural curl.

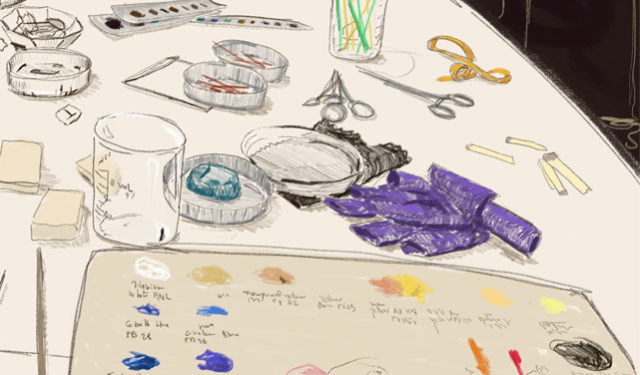

Bark scraping

Bark harvested in the fall or winter has a dark orange-red colouration on the cambium side. In bark scraping, also called sgraffito, the dark outer layer of bark is scraped away with a tool to reveal the lighter layers underneath, creating designs. Or, the opposite can be done—light coloured spring bark is scraped away to expose the darker layer underneath.

In both cases, the result is contrasting light and dark geometric designs, often with floral or animal motifs. This technique can be used to embellish all sorts of birchbark objects. Bowls and containers are often made from a single piece of bark, cut and sewn together with spruce root, then decorated on the exterior.

Bark biting

Called mazinibaganjigan in the Ojibwe language, bark biting is the custom of creating patterns on thin pieces of birchbark using the teeth. It is a pre-contact Indigenous art form practised by many Anishinaabeg peoples including the Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Odawa, Cree, and other Algonquian nations. Pieces of birchbark are peeled into very thin, individual layers.

The bark is folded in half several times and then bitten: incisors or eyeteeth create sharp lines, while molars are used for subdued impressions and shading effects. The biting creates impressions and thins the bark so that light can pass through.

When the bark is unfolded, it reveals a symmetrical design. Practitioners work spontaneously without preparatory plans or drawings. Biting was often done by women for entertainment or diversion, especially in social settings, with participants engaging in friendly competition to come up with the best designs or create a basis for stories.

Other uses

Birch bark is also used as a base for other art forms, for example porcupine quill embroidery and moose hair embroidery.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Croft, Shannon and Rolf W. Mathewes. “Barking up the Right Tree: Understanding Birch Bark Artifacts from the Canadian Plateau, British Columbia.” BC Studies No. 180 (Winter 2013/14): 83-122.

Gilberg, Mark R. “Plasticization and Forming of Misshapen Birch-Bark Artifacts Using Solvent Vapours.” Studies in Conservation 31, No. 4 (1986): 177–84.

Lebrecht, Sue. “Angelique Merasty: Birch Bark Artist.” Canadian Woman Studies Vol. 10, No. 2-3 (1989): 65-68.

McLuhan, Elizabeth. “Birch-Bark Biting.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published October 2, 2007; last Edited January 8, 2015.

Oberholtzer, Cath, and Nicholas S. Smith. “I’m the Last One Who Does Do It: Birch Biting, an Almost Lost Art.” Archives of the Papers of the 26th Algonquian Conference Vol. 26 (1995): 306-321.