Food: a Reflection of Changing Social Values

Browse the pages of cookbooks illustrating how our relationship with food has evolved over time.

March 25, 2020

This series of 12 articles written for the Shared Emotions project uncovers feelings, sensations and values buried in archival documents and looks at how they are shaped by the cultural and historical context of the time.

_______

The debate sparked by last year’s publication of the new Canada’s Food Guide is a reminder of how diet can be a very sensitive topic. Some people perceived its redesign as an attack on the country’s heritage and food traditions. If the issue raises such strong feelings, it is because how and what we eat is indeed a matter of culture and values.

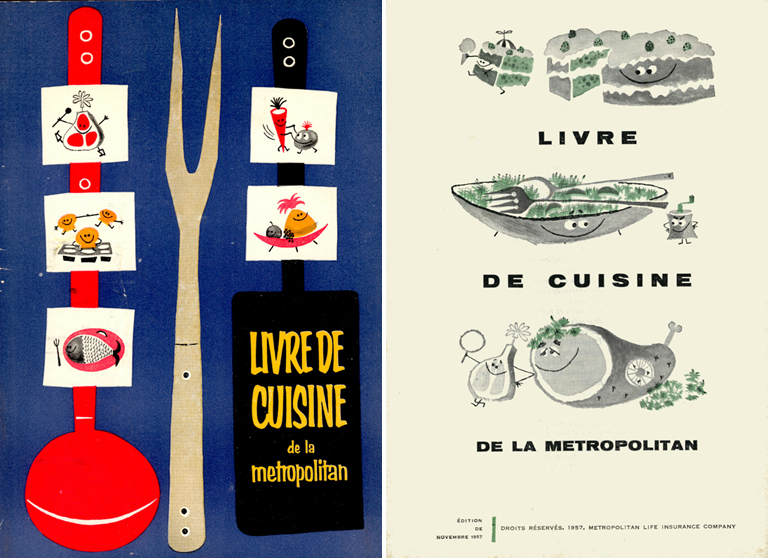

The McCord Museum’s collection includes nearly 1,000 cookbooks and recipe pamphlets. Those published over several decades (1918-1973) by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company captured our attention. During the 20th century, this type of communication tool was part of the advertising arsenal used by insurance companies to reach their clientele. By promoting a healthy lifestyle, they helped ensure that their policyholders stayed healthy (and saved them money, too!)1. To demonstrate the relevance of their products, these companies were careful to ground their advertising message in the social realities of the day and adapt it, over time, to reflect changing values and lifestyles2. In addition to containing recipes, these booklets offer insight into the evolution of attitudes about this essential aspect of human life: what we eat.

THE RATIONALIZATION OF COOKING

In the 1860s, Quebec underwent a major phase of industrialization and urbanization. This wave of change had a dramatic impact on the food industry. During this period, agriculture adopted industrial techniques. Technological innovations (like refrigeration) and the development of transportation infrastructure led to the increasingly widespread distribution of foodstuffs. It was the beginning of the age of processed food and mass consumption3.

Around the turn of the century, the modern science of nutrition began to evolve, generating new knowledge. Having identified the individual nutrients found in food (proteins, fats, carbohydrates, minerals, vitamins), this new science developed a rationale for using culinary practices to optimize their health benefits4.

These advances could even take hold in the domestic sphere, which became a testing ground for the principles of organization, precision, efficiency and hygiene used in industrial modes of production5. This scientific view of food contributed to the production-oriented attitude associated with the capitalist and nationalist ideologies of the era, promoting the idea that bodies were machines whose performance had to be constantly maintained and improved by the rigorous application of these principles6.

The 1918 edition of the Metropolitan Cook Book contains a clear reference to these principles:

“We all know that to live we must have food, but we do not all realize that we must eat the right kinds of food to be at our best and to work efficiently.”

The First World War forced Canadians to adapt their eating habits. During wartime, the tenets of nutritional science offered a solution to the challenge of providing the population with a healthy diet, despite the economic constraint of higher food costs. The same edition of the Metropolitan Cook Book provides information on the suggested daily servings for a man “of average size, who is moderately active” to be “well fed,” along with advice on purchasing and caring for food to ensure it is properly preserved and kept safe.

PREPARING FOOD THAT IS BOTH NOURISHING AND APPETIZING

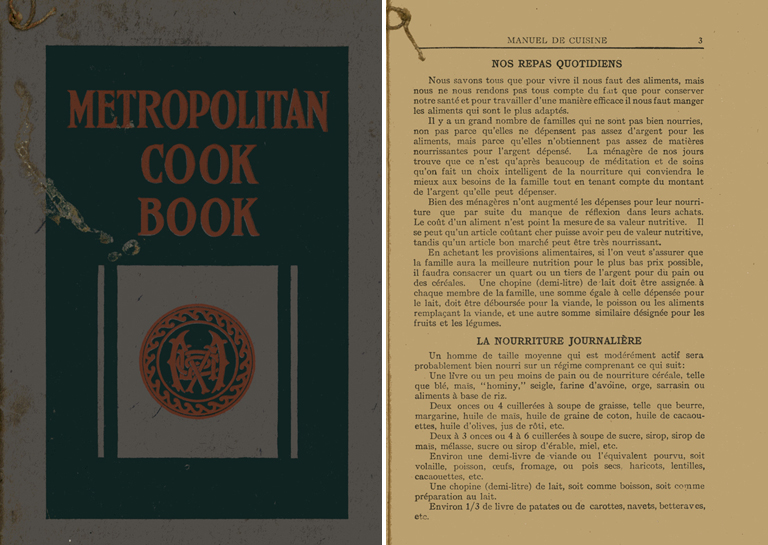

During the interwar period, the concern for a “healthful diet” remained, but there was also room for the pleasures of eating. In this mid-1930s edition of The Metropolitan Cook Book, housewives are urged to prepare family meals that are not only nourishing, but that also “quicken the appetite.”

The cover is less austere than that of the preceding version, featuring children overjoyed at the sight of what their mother is cooking. For the women in question, however, according to the precepts of the day, the joy of cooking did not lie in the pleasures of savouring the delicious dishes they prepared, but in the satisfaction of lovingly working for their families, to whom they were devoted7.

THE SEARCH FOR REFINEMENT

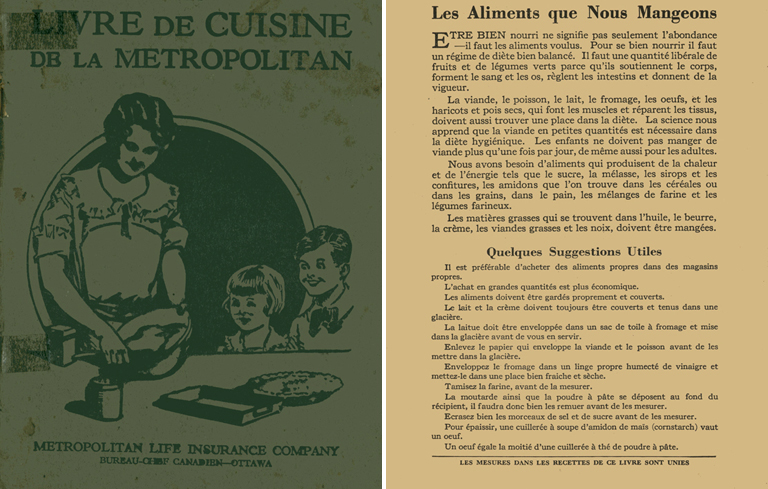

In the next edition, dating from the 1940s, the rhetoric of nutritional science is more subtle. The woman of the house still bears the heavy responsibility of ensuring her family is served nourishing meals that are also appetizing and feature a variety of foods.

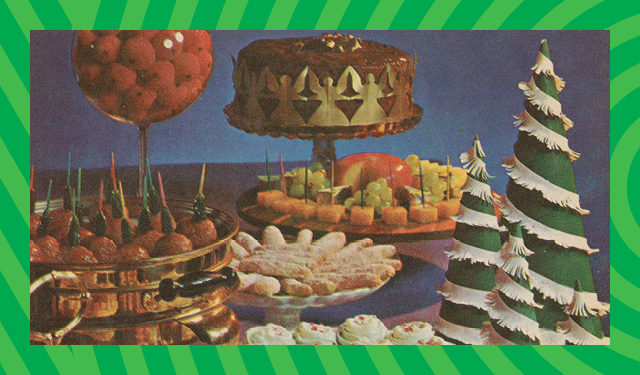

Towards the end of the 1940s, the idea of a gourmet food experience begins to appear, based more on novelty than on refined ingredients8. The colourful cover of this edition of the Metropolitan Cook Book illustrates that the taste for refinement also includes an attractive visual presentation involving a variety of shapes and colour combinations.

COOKING AS A FUN ACTIVITY

Consumers’ relationship with food changed during the postwar baby boom. The atmosphere grew more relaxed. The increased standard of living and availability of foodstuffs helped wipe away memories of wartime restrictions. Advertising, mass consumption and the use of household appliances transformed culinary practices9.

Now perceived as a social activity, cooking was meant to be fun, as suggested by the illustrations on the cover and throughout this 1957 edition. The science-based rhetoric that had introduced previous editions was dropped. While the organization of the booklet did not change much, there is greater diversity to the dishes as more variations are suggested. An openness to foreign cultures comes through with flavours that are a little more exotic.

MEALTIME AS A SOCIAL MOMENT

In the 1970s, the insurance company published a completely redesigned version of its guide, entitled New Metropolitan Cook Book. The introduction once again addressed the nutritional value of foods, but focussed primarily on the idea that mealtimes are an occasion to socialize:

“Above all, eating is, and should be, fun—a time to bring the family together around the table; a time to stop and reflect on the rich harvest provided by a bountiful land.”

Once seen as “perfect chefs,” in the mid-20th century, housewives became “perfect hostesses,” transforming meals into opportunities for discussion and social interaction10. The Metropolitan booklet’s new layout reflects this interest in eating as a vehicle for socializing. It presents the three meals of the day in order, noting the social and cultural dynamics associated with each: breakfast as an occasion “for the family to meet—even if it is a bit rushed,” lunch as “an opportune time to eat with friends,” and the importance of dinner as “a social highlight to be shared with relatives and friends.”

HEALTHY DIET AS A MEANS TO PERSONAL HAPPINESS

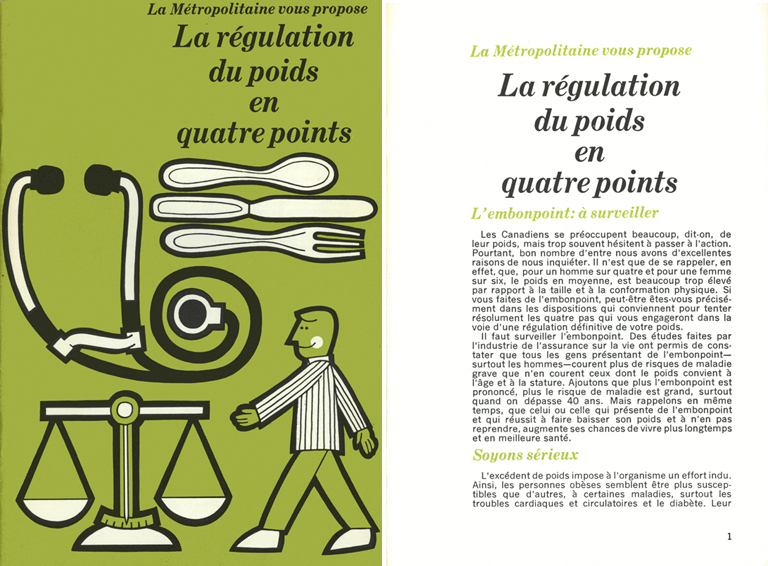

Recipe booklets were not the only publications created by Metropolitan Life; the company also occasionally covered related subjects, associated with maintaining the health and well-being of its policyholders. In the late 1960s, it published a booklet called Four Steps to Weight Control that promoted physical exercise and encouraged the fight against fat, cholesterol and calories. While it does not completely reject the pleasures of eating, it does recommend limiting what you eat:

“The secret to a healthy diet is to enjoy meals that offer a variety of foods, in moderate quantities. However, it is important to control your appetite at all times if you do not want to gain weight.”

Although the era saw a growing understanding of the very real risks associated with being overweight, this new concern also reflected a new awareness of the body and evolving standards of beauty and success:

“You will grow slender, feel and look your best without feeling hungry, and be justifiably proud of having reached the goal of finally feeling good about yourself.”

In this way, diet and its effects on the body—which used to be seen mainly as a public health issue—gradually become, the closer we get to today, a matter of personal success and happiness11.

TO LEARN MORE

- To learn more on the Recipes and Food Collection (C265)

- To learn more on the Shared Emotions project

- To learn more on the Textual Archives Collection

NOTES

1. Chantale Dureau, La publicité de l’assurance vie au Québec : stratégies et discours (1920-1960), M.A. thesis (Quebec studies), Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, 2007, p. 59.

3. Caroline Coulombe, Un siècle de prescriptions culinaires : continuités et changements dans la cuisine au Québec, 1860-1960, M.A. thesis (Quebec studies), Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, 2002, p. 20-21.

5. Caroline Coulombe, “Entre l’art et la science : la littérature culinaire et la transformation des habitudes alimentaires au Québec,” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, 2005, vol. 58, no. 4, p. 523.

6. Caroline Durand, Nourrir la machine humaine. Nutrition et alimentation au Québec, 1860-1945, Montreal, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015, p. 18.

7. Caroline Durand, “L’alimentation moderne pour la famille traditionnelle : les discours sur l’alimentation au Québec (1914-1945),” Revue de Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, 2011, no. 3, p. 65-66.

8. Caroline Coulombe, “Entre l’art et la science,” p. 530.

11. François Guérard, “L’émergence de politiques nutritionnelles au Québec, 1936-1977,” Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, 2013, vol. 67, no. 2, p. 183.

WHAT’S COOKING IN OUR ARCHIVES! A TASTE OF THE PAST

The Museum’s Archives collection includes nearly 1,000 cookbooks and recipe pamphlets produced between the mid-18th and early 21st centuries. Many were booklets published to promote a specific product or brand. Others are compilations of recipes carefully written out by hand or assembled in scrapbooks, chronicling timeless family traditions or, conversely, the latest trends of the day.

THANK YOU!

This project has been made possible in part by the financial support of Library and Archives Canada.