Article

| 3 min

For Your Eyes Only

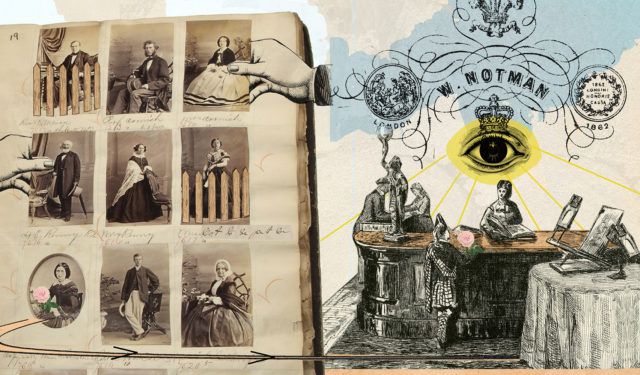

Not to Be Sold: Privacy at Notman’s Studio or Controlling One’s Image in the 19th Century (Part 3 of 6).

Sarah Parsons, Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Visual Art and Art History, York University

Vanessa Nicholas, PhD, Department of Visual Art and Art History, York University

Katy Lemay, Illustrator

June 28, 2022

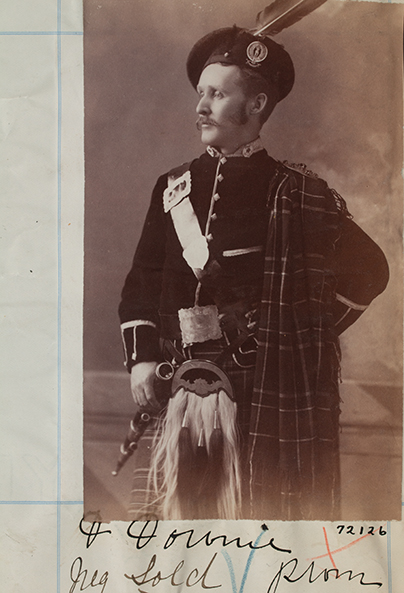

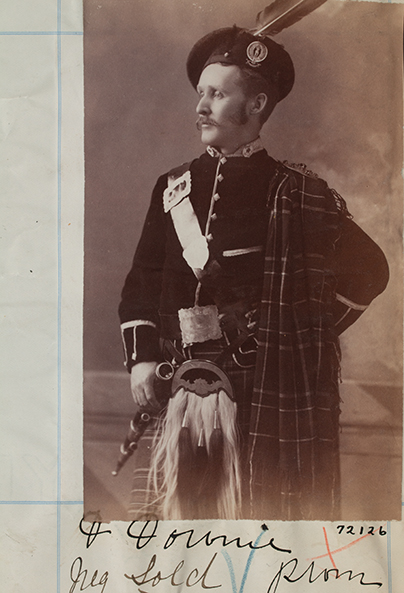

Two portraits of male sitters from 1884 suggest that a range of strategies was available to those who wished to limit images for private use. Mr. Downie presented himself as quite the Victorian dandy at Notman’s studio. The Picture Book includes a frontal and profile view of Downie in full Highland dress and a truly spectacular moustache, twirled at the ends. Oddly, the negative of the profile image was purchased, presumably by Downie himself, meaning no further prints could be purchased for this image.

William Notman, Mr. Downie, Montreal, 1884. II-72126.1, McCord Museum

Restriction: Neg Sold

SELLING THE NEGATIVE

While there are other examples in Notman’s records of negatives being sold, it was a decidedly rare occurrence. Negatives of this era were made of glass, so transporting and storing them was always a risky endeavour, and they required equipment, chemicals and know-how to make any prints. More often, negatives were purchased to be destroyed or simply to prevent any further prints from being made.

What might have inspired Downie or whoever commissioned his portrait to pay the extra expense for the negative, while placing no restrictions on the print sales of its partner image? Perhaps it was driven by Downie’s desire to have one image for private contemplation or for his beloved, an image that could not also circulate in his family albums or in the collections of his friends and military brethren.

EXCLUSIVE COPY

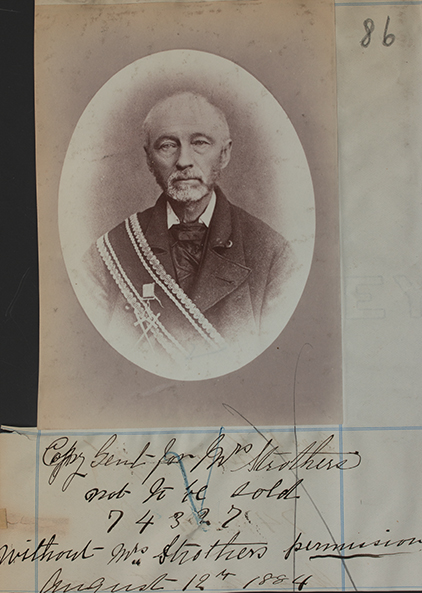

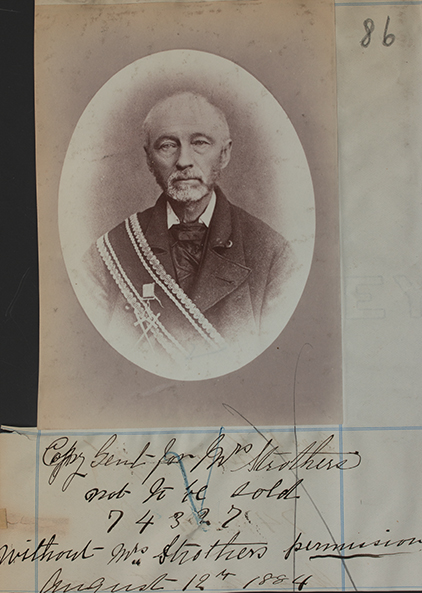

In comparison to the theatrical pose and elaborate regalia of Mr. Downie’s image, the oval headshot of a bearded, balding older gentleman is rather staid. The sitter wears an overcoat with a white collar and silk cravat underneath. A sash crosses from one shoulder across his chest.

William Notman, Portrait of a gentleman, copied for Mrs. Strothers, 1884. II-74327.0.1, McCord Museum

Restriction: Not to be Sold without Mrs. Strothers permission

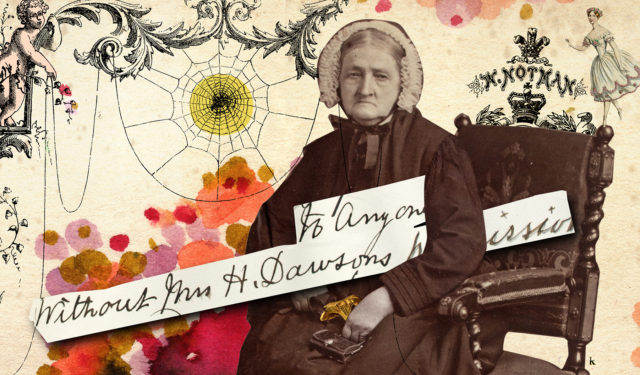

This little portrait may be less visually arresting than Downie’s, but it clearly held significant meaning for Mrs. Strothers. She brought the image to Notman’s to order a reproduction and left instructions that no other copies were to be made without her permission.

If the Notman staff’s use of underlining is any indication, her instructions were particularly forceful. The photograph and accompanying instructions point to both an intense desire for a private photograph and the impossibility of keeping photographs completely private.

After all, Mrs. Strothers’ order reminds us that anyone with a copy of a photograph could have multiple copies made, and that having a copy made by Notman’s studio necessarily meant moving the photograph through many sets of hands, generating multiple copies, and a record of the transaction. Producing photographic copies was such an important part of commercial studio business that most referenced it in their advertisements.

The series Not to Be Sold: Privacy at Notman’s Studio is supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

About the authors and the illustrator

Sarah Parsons, Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Visual Art and Art History, York University

Sarah Parsons is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Visual Art and Art History at York University, Toronto. She is the author of several texts on Notman including

William Notman: Life & Work (The Art Canada Institute, 2014) and “Notman’s Studio as a Space for Performance,” in Hélène Samson and Suzanne Sauvage ed.,

Notman: Visionary Photographer (McCord Museum, 2016). These articles are part of

Feeling Exposed: Photography, Privacy, and Visibility in Nineteenth Century North America, a multiyear project supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Sarah Parsons is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Visual Art and Art History at York University, Toronto. She is the author of several texts on Notman including

William Notman: Life & Work (The Art Canada Institute, 2014) and “Notman’s Studio as a Space for Performance,” in Hélène Samson and Suzanne Sauvage ed.,

Notman: Visionary Photographer (McCord Museum, 2016). These articles are part of

Feeling Exposed: Photography, Privacy, and Visibility in Nineteenth Century North America, a multiyear project supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Vanessa Nicholas, PhD, Department of Visual Art and Art History, York University

Vanessa Nicholas recently completed a PhD in the Department of Visual Art and Art History at York University. Her research interest is in nineteenth century Canadian visual and material culture, and her doctoral dissertation is a close study of the floral embroideries found on three historical Canadian quilts. She is a Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholar, and she was the 2019 Isabel Bader Fellow in Textile Conservation and Research at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre.

Vanessa Nicholas recently completed a PhD in the Department of Visual Art and Art History at York University. Her research interest is in nineteenth century Canadian visual and material culture, and her doctoral dissertation is a close study of the floral embroideries found on three historical Canadian quilts. She is a Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholar, and she was the 2019 Isabel Bader Fellow in Textile Conservation and Research at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre.

Katy Lemay, Illustrator

Katy Lemay’s passion for visual arts dates back several decades. She has a degree in graphic design from Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) and has become a well-respected illustrator. While she finds inspiration for her complex collage illustrations in vintage magazines and photos, her ultimate source of ideas is words.

Katy Lemay’s passion for visual arts dates back several decades. She has a degree in graphic design from Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) and has become a well-respected illustrator. While she finds inspiration for her complex collage illustrations in vintage magazines and photos, her ultimate source of ideas is words.

https://www.musee-mccord-stewart.ca/en/blog/for-your-eyes-only/

Copied

Error

Copied

Error

Share this content