From art action to social action

A profile of Catherine Boivin, Atikamekw artist and Museum intern, who talks about her practice and artistic and social ambitions.

August 3, 2020

Legend tells the story of a mother who loses her child, Kwei. She looks for him her entire life everywhere, in the forest, in her dreams and in the eyes of strangers. “Kwei? Kwei?” The call was taken up by others and turned into a greeting. Catherine Boivin tells me this tale over the phone from Odanak, an Abenaki village near the Saint-François River. The story is an Atikamekw legend that explains the origin of the expression Kwei Kwei, which means “hello.”

“This legend has a lot of meaning for me and my family,” says Catherine from the other end of the line. She tells me other stories as well, but they’re not legends. They’re about missing, dead or abducted children. This is the inspiration for her video work called Kwei, which is named after the legend. “It’s not only for my ancestors; it’s mostly for my mother, grandmother and aunts,” she confides. It’s a lot less gentle than a legend.

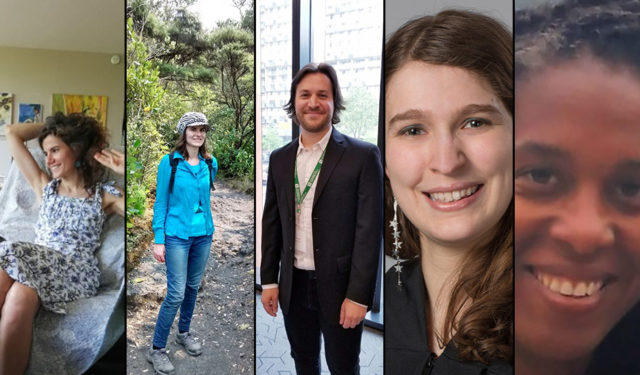

An Atikamekw artist, Catherine Boivin grew up in the Indigenous community of Wemotaci and is studying for a bachelor’s degree in visual arts at the Université du Québec à Montréal. She is currently an intern at the McCord Museum as part of the Conseil des arts de Montréal’s CultivART program, which enables several Montreal museums to deepen their ties with Indigenous creators. Since the beginning of the year, Catherine has been working with the Museum’s Education, Community Engagement and Cultural Programs team to create an educational activity focused on the concepts of reconciliation and decolonization. Her project will be integrated into the new permanent exhibition of the Indigenous Cultures Collection, which will be open to the public in June 2021.

Catherine is inspired by an initiative that began as part of the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation in 2017. It proposes 150 actions to reverse the process of colonization and assimilation and reconcile Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada. “One hundred and fifty concrete actions, such as buying a book written by an Indigenous person,” suggests Catherine. She quickly saw the potential of an internship in a social history museum. Her artistic perspective is well suited to the educational and participatory vision of the McCord Museum.

Through her multidisciplinary art work, she explores the relationship between the body, material and media. “For me, performance is also about ritual,” she adds. Catherine defines her practice as Art Action, performance action aimed at creating not only a work of art but also having an impact in society. “To change the world,” she says laughing. To move and inspire. Her art leaves me with the feeling of power rooted in reality.

Catherine adds that she strives to sublimate the oral tradition and her ancestors’ precious relationship with the material by exploring the themes of cultural appropriation and the reappropriation of the image. “In my work, I also talk about my perception of myself.” This is because reappropriating your image is not only about reconnecting with the culture of your ancestors, it’s also about asserting yourself as an individual.

“No two Indigenous artists are the same or will create the same thing.”

When Catherine tells me she would like to be an exhibition curator in the future, I better understand the scope and ambition of her approach. For the young artist, this internship is an opportunity to explore the principle of Art Action through a new means of expression – the museum.