Gardens of yesteryear and today

Public markets, subsistence farming and large-scale agriculture: discover how our food supply has changed over the centuries.

July 11, 2022

This hand-painted photograph illustrating the theme of abundance features a blue sky, children, and containers overflowing with potatoes, cabbage, squash and other vegetables. They are market gardeners posing proudly with their bountiful harvests before selling them at the market.

DELICIOUS ABUNDANCE

There is something quite joyous about these images from the Museum’s collection, something festive in this delicious abundance. The most important aspect of a public market, where market gardeners come to sell the fruit of their labours each year, is not just the plentiful agricultural products. It is also the chance for those who enjoy eating these crops to connect with those who have carefully raised these plump, colourful beauties.

| Don’t miss Eating local, a photography exhibition on McGill College Avenue |

A lot has changed over the past century when it comes to our relationship with food. However, the renewed popularity of gardening during the pandemic, along with the enduring joy of exploring the extraordinary offerings in our public markets, have brought us a new appreciation for a time-honoured pleasure: that of experiencing close contact with the bounty of the land and the artisans who tend it.

MARKET DAYS

During the 19th century and a good part of the 20th century, a flood of horse-drawn carts, full of vegetables, would stream into Montreal on market days. This lively crowd would begin filling Bonsecours Market and Jacques Cartier Square as of the wee hours of the morning.

One can just imagine the hubbub of the throng, bathed in the glow of dawn, and the heady mix of a thousand strange smells. The air would ring with the sounds of horses neighing, heels clicking on the cobblestones, customers haggling, and farmers loudly proclaiming the virtues of their fresh products. In those days, the market was the noisy, fragrant and, above all, lively, heart of the city.

NEED AND PLEASURE

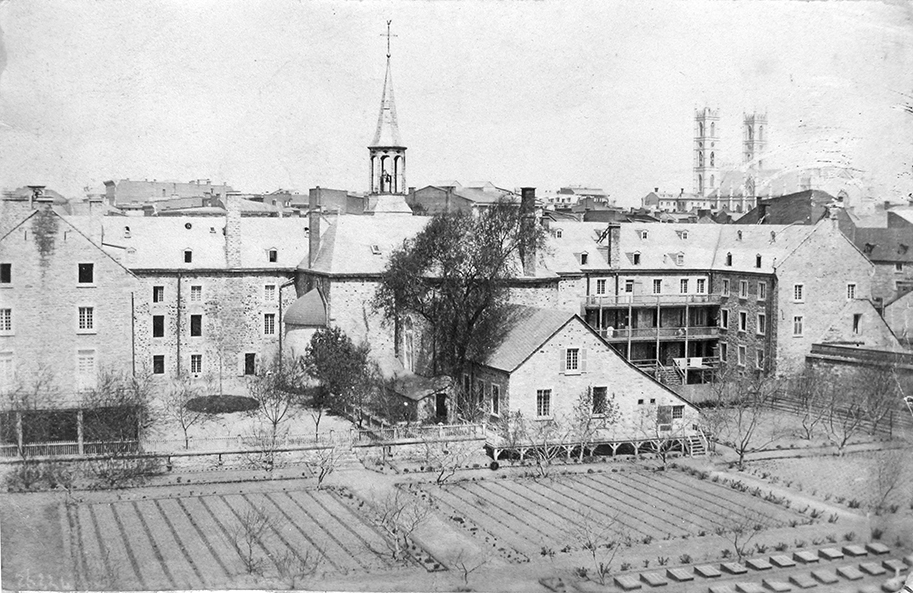

For many years, Montreal religious communities were examples of self-sufficiency. A few blocks from the market, a completely different atmosphere reigned at the Saint-Sulpice Seminary where, in the oldest private garden in North America, a wide variety of fruit and vegetables were grown.

Further west, the Grey Nuns maintained extensive gardens where they grew a wide variety of vegetables and berries that supplied the community with a portion of what it needed. Up until the 20th century, Montreal was dotted with subsistence gardens and small farms that enabled city dwellers to feed themselves with relative autonomy.

Garden layouts were informed by over a century of knowledge. The meticulous, passionate art of arranging plants to keep destructive insects away and maximize growth was handed down from one generation to the next.

| Are you interested in food? Read the article Food: A reflection of changing social values and discover recipe pamphlets illustrating how our relationship with food has evolved over time. |

This relation to food is in stark contrast to today’s model of industrial monoculture farming, which takes place far beyond the city’s suburbs.

ILLUSORY ABUNDANCE

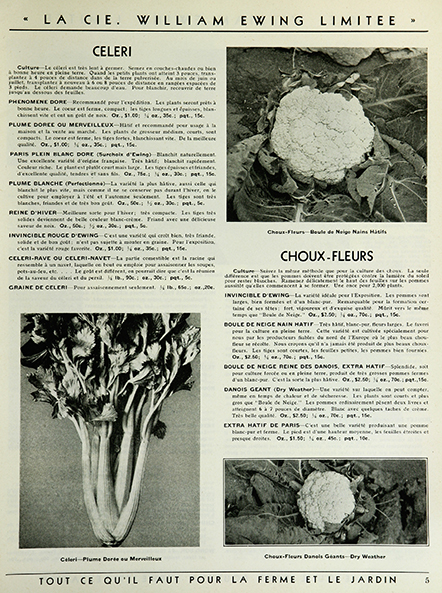

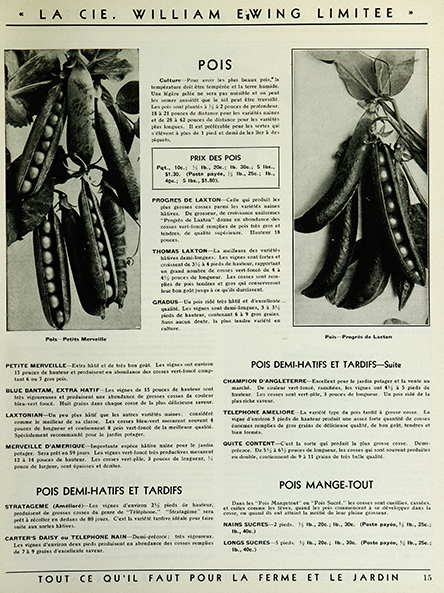

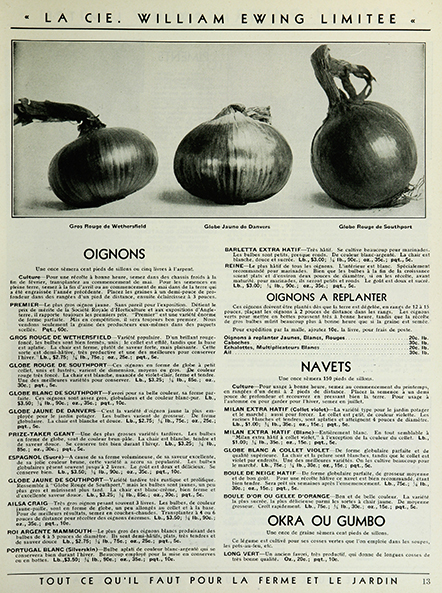

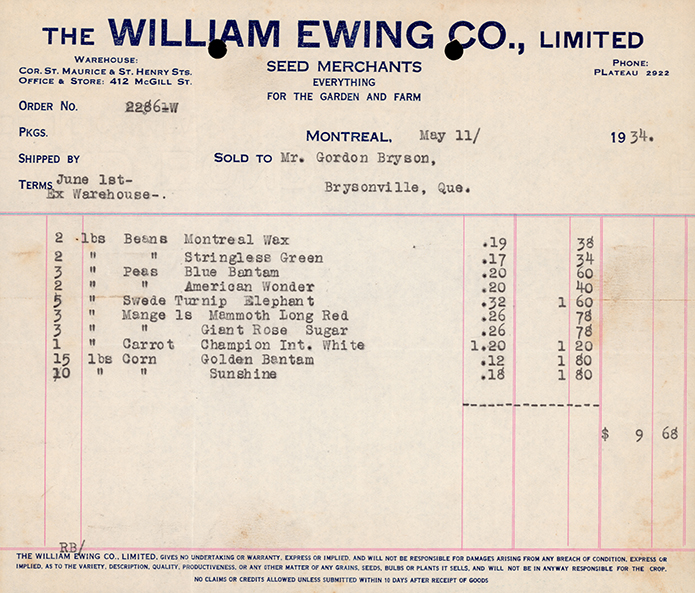

If our ancestors were to enter a modern-day supermarket, they would no doubt be astonished by the selection of fresh produce and the many exotic fruits and vegetables. However, we would be equally surprised by the contents of a 1936 seed catalogue from the Museum’s archives, published by the William Ewing Co., Limited.

Though the catalogue makes no mention of dragon fruit, papayas or mangos, it does list 11 varieties of cucumbers, 4 of spinach, 13 of onions, 10 of radishes, and many more. The various descriptions made me start dreaming of rounded carrots and long radishes, and I tried to imagine what they tasted like, just as my ancestors might wonder about an orange.

The produce found in today’s grocery stores differs from that of yesteryear because it is driven by a different need: profitability. Though we can enjoy avocados and oranges 365 days a year, what has become of the Spanish black radish and the Nantes half-long carrot? Or the Chalk’s Early Jewel, a dark red, meaty tomato? Or forage plants, Southport Yellow Globe onions and the once legendary Montreal melon?

Indeed, up to the 1930s, Montreal had its own melon. Similar to a large cantaloupe, but green-coloured and with a slight nutmeg flavour, it was a popular export to restaurants and hotels in the United States. Today, few people even know that this melon existed and even fewer remember what it tasted like.

My local grocer sells just one variety of each vegetable, selected, one suspects, more for its conservation qualities than for its refined taste. However, though people unfortunately tend to forget this, Montreal’s public markets are still alive and well.

From the Jean-Talon Market to the Atwater Market, one can still rise at dawn to meet local farmers busily filling their stalls with freshly picked produce.

Wooden crates may have been replaced by plastic boxes, but the essential experience is the same: one has the precious opportunity to connect with the individuals responsible for growing this abundant harvest.