Garnotte’s Mirror to the world

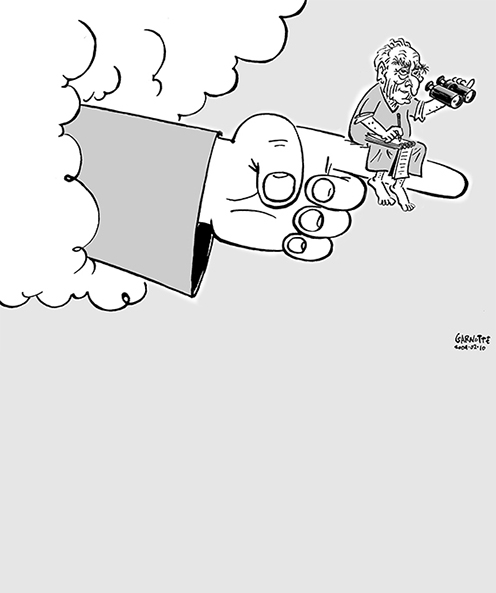

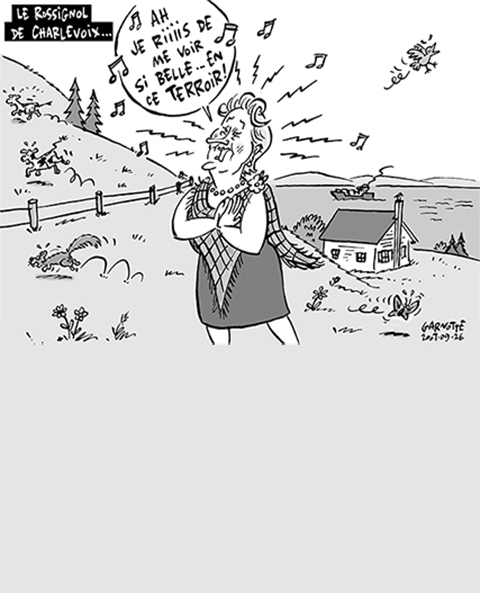

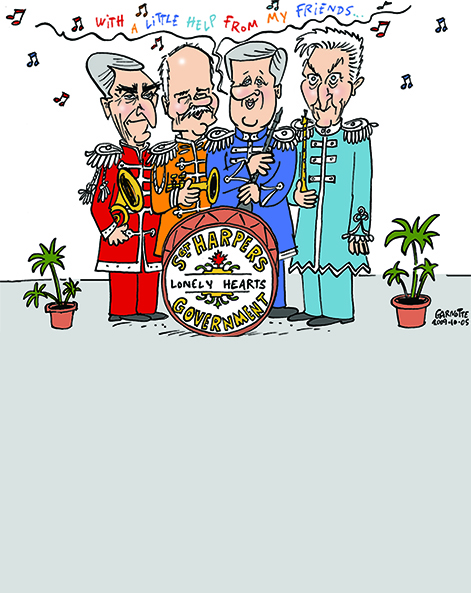

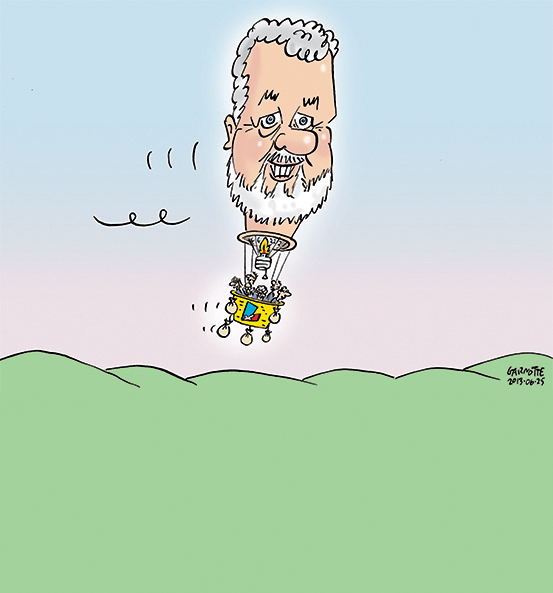

Discover the work of Garnotte—a portrait of society, captured in cartoons.

May 2, 2024

The public can now view 2,175 original Garnotte cartoons online, one by one, thanks to the McCord Stewart Museum’s efforts to catalogue, preserve and promote them.

Cartoonist Michel Garneau, aka Garnotte, spent years depicting the news in his drawings. He is best known for his work at the daily newspaper Le Devoir, where he was the editorial cartoonist for many years. He was celebrated. He was beloved. Every morning, his cartoon was the first thing readers would turn to.

How many cartoons did Garnotte produce? The truth is, he drew many more than were published. At Le Devoir, he used to produce dozens of drawings every day, one after the other, from morning until deadline. I have seen him at work. He would make sketches to test out his ideas, trying things from different perspectives. Once he was satisfied with a drawing, if the news suddenly took a different turn, he would immediately move on to something else.

| Discover all Garnotte’s cartoons on Online collections |

Sometimes, of course, he would experience writer’s block. “What’ll I draw today?” he would ask everyone around him, trying to find out what other people thought was special about the day’s news. No one ever worried about him. They knew that he always came up with something, and that it was always good.

Garnotte began drawing for Le Devoir in 1996. He had already made a name for himself at magazines like Temps fou, Croc, and Titanic, and had worked for the CSN newsletter, notably illustrating articles by writer Pierre Vadeboncoeur. He also made children laugh, and think, in the pages of Les Débrouillards. I have likely forgotten some of his other publications. In any event, he has spent his entire life drawing. Like most cartoonists, he delighted in his Sisyphean task.

At Le Devoir, his work was invariably published in the same space, on the editorial page. Newspapers like that provide a cartoonist with a special platform. His drawings were always in the same location, and the public expected to see them. Everybody who read the paper would look at his work. Editorial cartoons are typically the most popular news item in a paper given that they are almost impossible to avoid. As a result, the editorial cartoonist’s work ends up being closely identified with the newspaper’s image. Garnotte knew this. He was aware of his reputation and knew his worth. That being said, he did not let it go to his head. That was not his style. It is hard to imagine anyone more kind and considerate than Garnotte. However, this did not prevent him from showing his teeth at times in his work as a cartoonist.

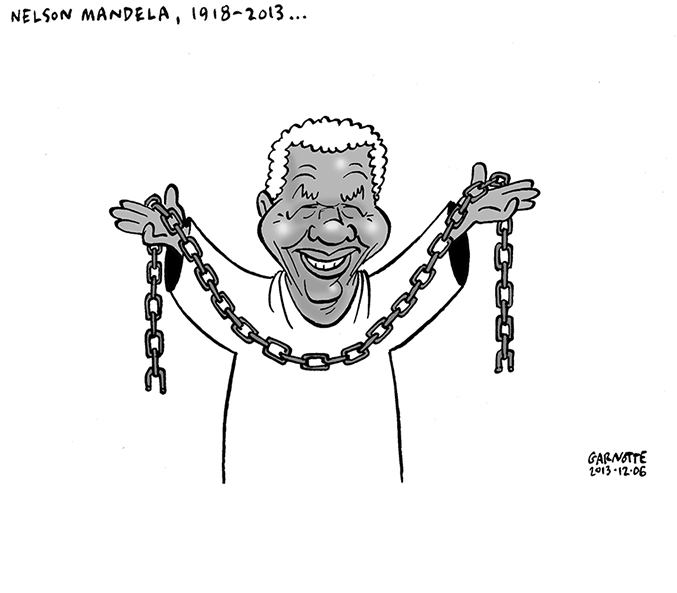

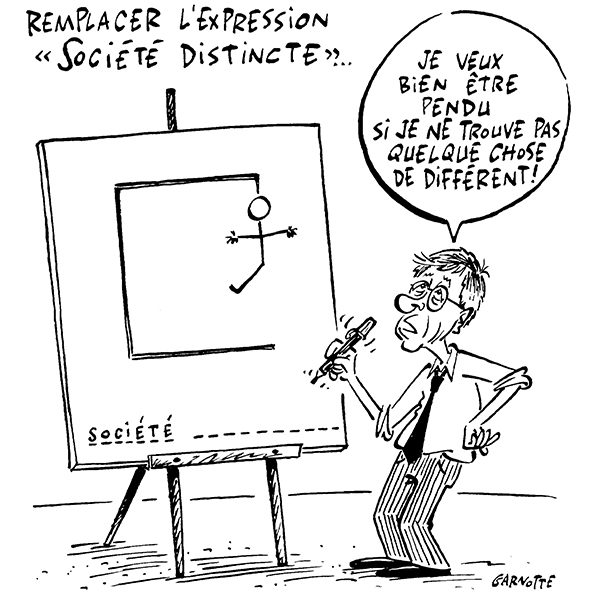

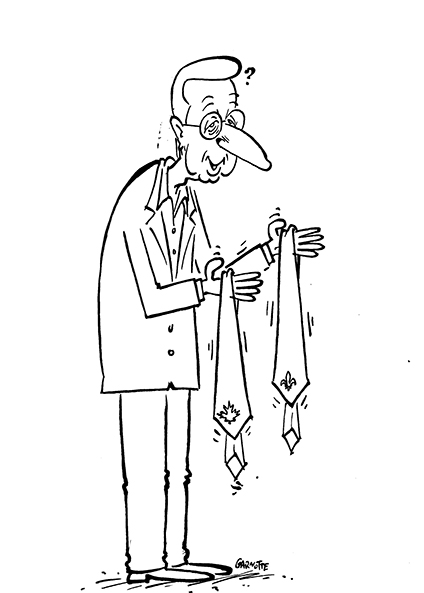

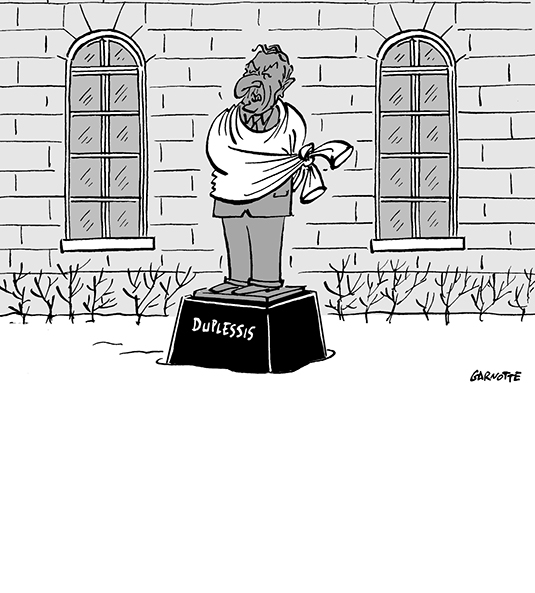

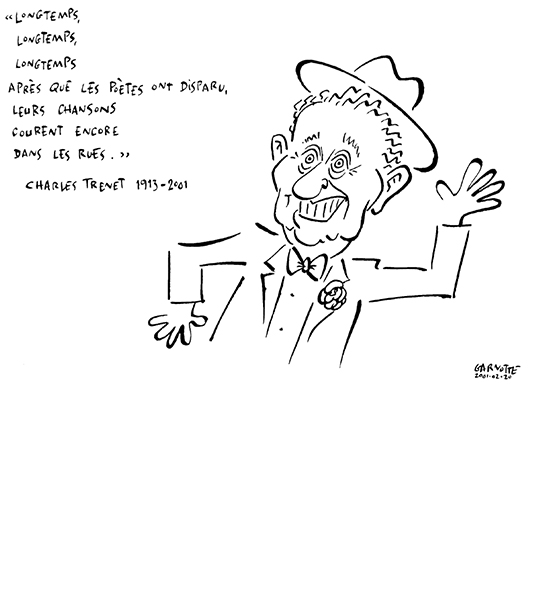

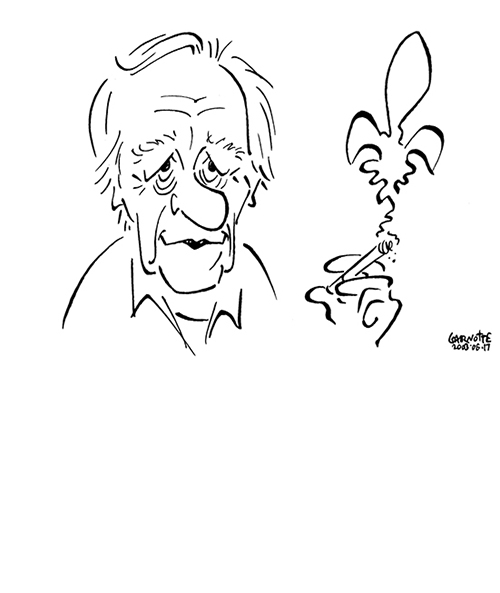

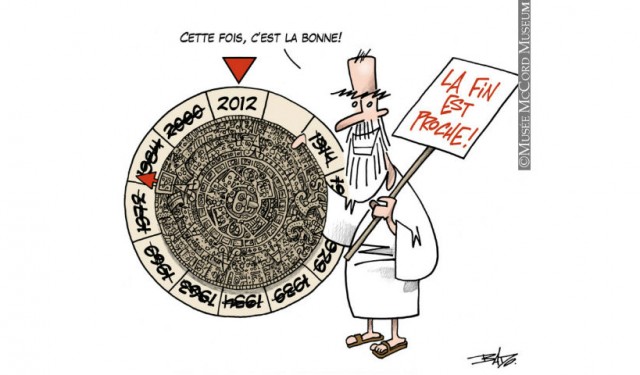

The series of Garnotte cartoons recently acquired by the McCord Stewart Museum covers a particularly active period in his career, from 2006 to 2013, and includes most of the cartoons he published during this time. However, to fully appreciate Garnotte, to comprehend his logic as well as his talent, one must examine the trajectory of his drawings to identify his viewpoints, convictions, likes, and dislikes. Such an exercise quickly reveals a certain sensitivity, a sense of relativity. A predilection, not for a body of fixed ideas, but for principles like freedom, generosity, and faith in universal ideals.

During the years I worked alongside him, Garnotte would enthusiastically plunge into the news every morning. Always approachable, friendly and cheerful—never arrogant—he was an excellent newsroom colleague. Even when he was bit overwhelmed by the latest stories, a condition that affects all of us in the profession some days, Garnotte would find a way to make everyone laugh, giving those around him a boost, some joy, perhaps without his even realizing it.

I remember once sharing a meal with him and Plantu, the cartoonist for French newspaper Le Monde, along with some other colleagues. I was struck by how the two artists immediately developed a natural rapport and affinity. They obviously shared a common sense of responsibility with regard to society and politics, though they each had their own approach to editorial cartoons. In other words, both were absolutely obsessed with the news.

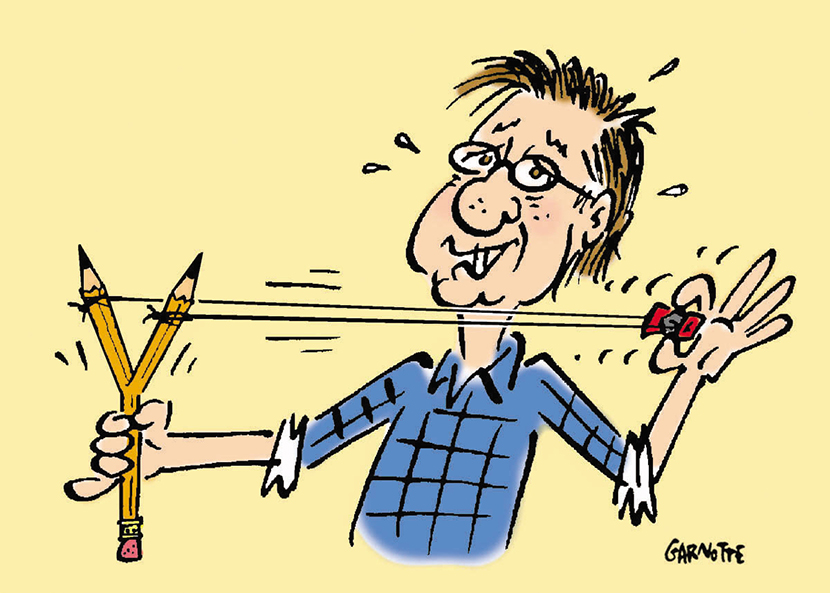

Like an archer, Garnotte would try to take aim at the perfect target every day in his drawing. He was good at it. A small television on his desk was often on so he could follow the news. He would also listen to the radio. And, of course, he would read several newspapers. Back before everything (or almost everything) could be found online, we used to receive paper copies of many newspapers, both local and international, throughout the day. But most importantly, Garnotte would listen to the conversations of those around him. What had caught his colleagues’ attention? What were people talking about? Could it be the topic of the day’s cartoon? He took an interest in everything, in every area imaginable. Unlike regular journalists assigned to cover only one aspect of the news, he could find his inspiration in absolutely anything.

Though a humorist, he was very serious about his job. He dedicated himself to his work, always seeking for fresh ideas. He looked for that almost magical blend of elements that would enable his drawing to create a powerful connection between a fact and an impression. Garnotte also paid close attention to the few words that would grace his drawings. He sometimes spent a long time reflecting on what to write. He wanted to find just the right phrase, short and to the point. I think the public probably has no idea what is involved in producing a political cartoon.

Garnotte would often drop by my office. His was located directly across from mine, on the other side of the newsroom. I was not the only one that Michel would occasionally ask for advice. I was honoured to do it. I would have greatly preferred to know how to draw than write, so I loved discussing with him. We got along very well. After crossing through a sea of desks to get to mine, he would show me a series of drawings. “What do you think of this one? Look, I tried it this way as well… Would this version would be better? I also did this one, which is different…” While these visits did not occur daily, they did take place regularly.

Actually, Garnotte did not always need to seek us out directly. Many of us would, throughout the day, drop by his office or buttonhole him when he passed by. “Michel, where are you going? Michel, are you going to draw about this or that? Michel, I think it would be a good idea to…” There were likely many of us who dreamed of being able to draw rather than write… Things went on this way for years at Le Devoir, in what was very much a family atmosphere. Sometimes, Garnotte would use one of our suggestions. But more often than not, our rather silly ideas would just bolster those he had already thought of.

In the movies and on television, newsrooms are always portrayed as bustling places. People shout, run around, get angry, argue, yell, bicker and fall out, only to start the whole thing over again the next morning. In the public’s imagination, a newspaper resembles a battlefield. In reality, newsrooms are oases of relative calm. Cartoonists, like ordinary journalists, need this calmness, which is by no means dull, to get through the day.

For many years, six Garnotte cartoons appeared in Le Devoir every week, one for every day it was published. When Garnotte had to miss work, he would sometimes produce an extra drawing in advance. When he was on vacation, the editorial team would republish a selection of his more timeless drawings. This meant readers almost never missed seeing a Garnotte cartoon. He was always there. An absolute must. For years.

However, his editorial cartoons, the ones now preserved at the McCord Stewart Museum, were not the only drawings he published. Garnotte would produce many others throughout the year, many of them specially commissioned by the newspaper.

For example, he might be asked to create original drawings for a thematic issue, or an illustration for an event sponsored by Le Devoir. His drawings were also used to illustrate the paper’s subscription campaigns and annual holiday cards. In other words, the black inkwell attached to his tilted drafting table was left open most of the time so he could replenish his pen.

His office displayed signs of the world in which he lived. Back when Le Devoir was still headquartered on the 9th floor of an old building on De Bleury Street, his walls were covered with drawings, stuck one on top of the other: images of George Bush Jr., Paul Martin, a hilarious Jean Chrétien, a lanky Bin Laden, a preening Bernard Landry, sketches of Stéphane Dion, and so many others. Although Garnotte’s work was incredibly diverse, I always felt there was a part of him in every one. Something that reflected his personality, that was disarmingly straightforward, just like him.

His walls were also plastered with photos, press clippings, and reproductions of works of art. I remember The Tower of Babel, a famous Bruegel painting that was very appropriate for the setting, and Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

With a glazed half wall somewhat insulating his workspace from the activity in the newsroom, Garnotte would settle into his cozy cubicle to create his cartoons every day. The paper’s previous cartoonist, Serge Chapleau, used to work in the adjoining office.

Every morning, Garnotte would attend the editorial meeting, usually run by the editor-in-chief and managing editor, to discuss which topics the newspaper would be covering. Bernard Descôteaux, who was managing editor of Le Devoir from 1999 to 2016, thought very highly of Garnotte, and it showed. The two men enjoyed a relationship of mutual respect.

Bernard Descôteaux died in early 2024. When I went to pay my last respects, I was surprised to see a Garnotte cartoon of Descôteaux hanging on the wall of the funeral home, next to a slideshow of photographs depicting Descôteaux’s personal and public life.

Although we view an endless stream of images every day, it occurred to me then that cartoons are—more than ever—a north star in the sky of our lives. They illustrate the essence of not only individuals, but societies. In short, cartoons hold up a unique mirror to the world, and I would like to take this opportunity to thank Garnotte for sharing his with us. They teach us how to better see and understand ourselves.

1994-2004

2005-2013

This project was made possible by the Aide au virage numérique program from Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ).

![]()