Happy Memories of Montrealers in Paris

Emerging as a major tourist attraction in the 19th century, the City of Light beguiled the Montrealers drawn by its charms.

January 5, 2020

This series of 12 articles written for the Shared Emotions project uncovers feelings, sensations and values buried in archival documents and looks at how they are shaped by the cultural and historical context of the time.

______

Last December 31, like every year, tens of thousands of people assembled on the Champs Élysées to celebrate New Year’s Eve. The many revellers enjoyed the evening’s cheerful atmosphere and the magnificent festive lights that make this legendary boulevard—known since the late 19th century as the “most beautiful avenue in the world”1 —even more enchanting. Indeed, Paris has long used its charms to captivate the hearts and eyes of visitors.

In an October 16, 1894, letter to his son Georges Ovide Leclère, Georges Samuel Leclère recounts his visit to the French capital. He and his wife Corinne Turgeon were spending time in Paris as part of a long European sojourn. Leclère is clearly enjoying his stay in Paris. His enthusiastic letter suggests that he is savouring every minute of his time in the city recognized for its vibrant cultural scene. In the late 19th century, many upper middle class visitors from North America were beguiled by the City of Light, drawn by its historical attractions and the charms of the Parisian lifestyle. Leclère, however, is not simply interested in seeking out intense experiences during his stay. He is also pleased to accumulate a store of happy memories to share.

“[…] everywhere I go, I am gathering pleasant experiences to enliven our cozy evenings en famille when I return […]”

P731/E

THE FEVERISH ACTIVITY OF THE GRAND BOULEVARDS

One of Leclère’s most memorable impressions of Paris is the great beauty of the Sainte-Chapelle, where he has the opportunity to attend the solemn ceremony marking the courts’ return to work after their summer recess.

“This ceremony takes place in the Sainte-Chapelle, one of the most beautiful churches in Paris. It was built, I believe, under the reign of Louis XIII2. The extraordinary stained-glass windows, which date from the same era, are intricately designed in an awe-inspiring array of colours to delight the eye.”

P731/E

However, judging by the many lines he devotes to the topic, Leclère’s favourite thing about Paris is its lively boulevards.

“[…] I took many pleasant strolls along the capital city’s grand boulevards, which seem to be the designated meeting place for visitors from around the world. Nothing is more charming and enjoyable than the immense boulevards that Paris seems to specialize in. They have the prettiest shops with windows that draw the eye to dazzling displays, arranged with exquisite taste, accentuating the beauty of the fabrics and objects for sale. The boulevards are also home to wonderful cafés frequented by those living the ‘high life,’ that is, artists, writers and distinguished foreigners, like us!! Hmm! There are times when all these cafés are packed with customers dining or having a drink at a sidewalk table, and I can tell you that one can spend a pleasant hour enjoying a cocktail, smoking a fine cigar, and watching the elegant denizens of Paris pass by. Among them, one can easily distinguish the coquettish courtesans and elegant demimondaines that Paris is known for, who are said, perhaps justifiably, to be the most friendly and witty, and to have “true style.”

P731/E

The French capital clearly lived up to Leclère’s expectations. After all, in the late 19th century, the city’s many attractions were well known. A mecca of elegance and amusement, Paris rivalled London as the modern city par excellence. Its exhilarating modernity could be seen in the urban planning exemplified by Haussmann-style buildings, as well as in the never-ending urban spectacle unfolding under the amused gazes of strollers enjoying the lively atmosphere of the Grand Boulevards3.

Based, in part, on the emergence of consumer culture, the French capital’s enviable reputation started to establish itself by the mid-19th century. The development of print media helped disseminate an idealized image of Paris to a broader audience4. In fact, North American tourists preparing to explore the City of Light already knew a lot about it, thanks to descriptions found in guidebooks, magazines and travel accounts. Like Georges Samuel Leclère, these publications extolled the city’s beauty and cosmopolitanism. Various travel accounts also highlighted the colourful crowds thronging its cafés, restaurants, theatres and major avenues, and unfailingly raved about the refined luxury of its magnificent department store window displays5.

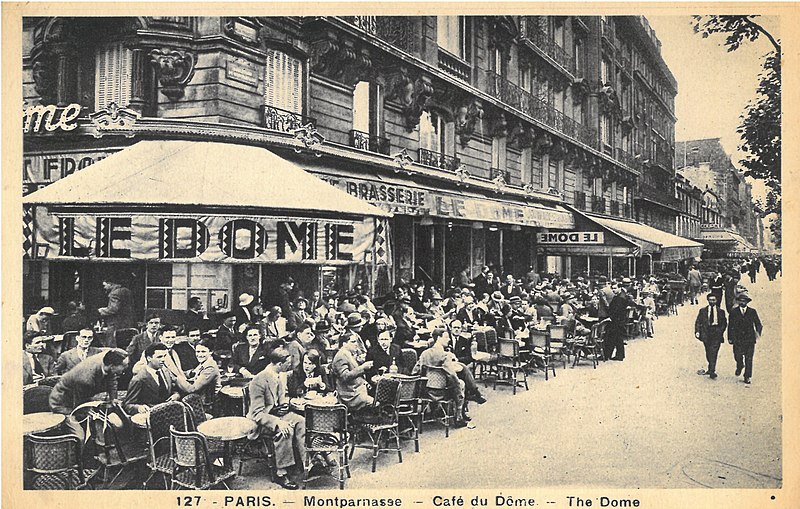

THE HEADY MONTPARNASSE CAFÉ SCENE

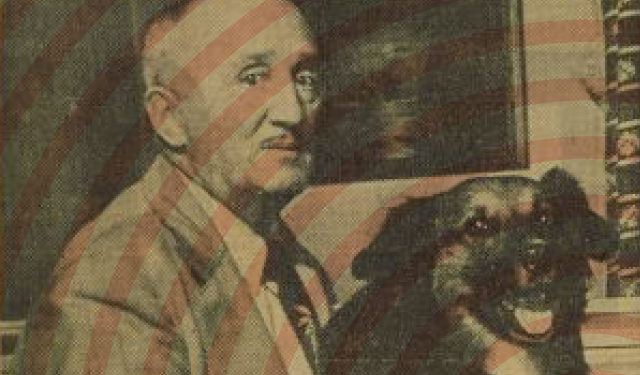

As Leclère’s letter illustrates, Paris cafés were also among the legendary sites popular with tourists. Several decades later, following the death of celebrated Quebec painter Clarence A. Gagnon in January 1942, his friends reminisced nostalgically about the good times spent with him and his wife in Paris. In a letter to Gagnon’s widow, Gilbert Wilson shared precious memories of spending evenings with the couple in the cafés of Montparnasse.

“I have so often recalled those days in Paris when we called on you both at your studio, and later went to the Dome [sic] or Cupole [sic]6 – they were memories of friendship and happiness which will live, and bring both of you back to me, and to Lucile.”

P116/E2,1

During the interwar period, Montparnasse became the new artistic centre of Paris7. Along with the artists came the bohemian spirit that had formerly inhabited Montmartre8, a spirit characterized by a certain insouciance, the search for an artistic ideal and a liberated lifestyle free of social dictates. During the 1920s, this colourful, lively neighbourhood was also a hub for many Americans fleeing Puritanism and Prohibition9. In addition, Paris’s vibrant cultural scene and major artistic institutions and museums made it very popular with foreign artists. Young Canadian painters were no exception and, as of the late 19th century, many travelled there to further their training10. Gagnon himself studied at the Académie Julian in 1904-1905 and for many years kept a studio on Falguière Street.

Clarence A. Gagnon’s correspondence occasionally chronicles the eclectic, intoxicating atmosphere of the neighbourhood and its cafés. The Café du Dôme, in particular, known at the time as the gathering place of writers, artists, art dealers and connoisseurs of art, seems to have been one of his favourite haunts, though he was perhaps a little too fond of it. In a letter dated December 21, 1925, Montreal art dealer William R. Watson voices concern about Gagnon’s productivity. Expressing a somewhat biased viewpoint, given that he was hoping the artist would send him some paintings for his gallery, Watson encourages him to stay away from the many distractions found in Paris.

“I can well understand your own difficulties, and believe eventually you will have to escape the social influences and distractions of the Dome [sic], and put your whole time into some serious and sustained work…”

P116/D8

The Dôme’s tremendous fame and its popularity with tourists was sometimes a disadvantage. In a poem he sent to Watson in 1929, Gagnon uses sarcasm to underscore the superficiality of the colourful crowds frequenting the area.

“Montparnasse

If ever you’re thinking of making your home

Within the environs subtending the Dôme

You’ve got to be odd, by God.

You dont [sic] need to write, and you dont [sic] have to paint,

As long as your aspect suggests what you ain’t;

You dont [sic] have to act, and you dont [sic] have to dance

As long as your coat never matches your pants.

You’ve got to look odd, by God.

No atom of thought in your brain cells need germinate

As long as your sex is a bit indeterminate.

No troublesome thought-waves your calm life need jostle,

As long as you look like, say Paul the Apostle,

You’ve got to seem odd, by God.

You never come out in the street before noon,

You’re living in sin, with a Belgian quadroon,

(Or a Russian dragoon, if you think you’d as soon).

Cause that’s pretty odd, by God.

You sit at the “Dôme” and you drink with your set,

It’s best if you keep a small lynx for a pet.

You talk of the Arts and matters aesthetic,

It needn’t make sense, if its [sic] just energetic;

You rather disparage the franc and the dollar,

You wear an old sock for a hat and no collar;

Your passion for life, can be pallid and formal

As long as you never let on that you’re normal.

And what if your looks your true actions belie.

Its [sic] all just a dream as the tourists walk by.

The tourists all love it, and wish they could try,

They think that you’re odd, by God, by God,

The tourists just know that you’re odd, by God.”

P116/D8

Whether the city was described as beautiful, charming, exciting, stimulating, captivating or even too touristy, for both Leclère and Gagnon’s friends, Paris was nonetheless a crucible in which unforgettable memories were forged.

“The four of us had so many good times together in Paris, it is nice to remember them sometimes, but life goes on […]“11

P116/E2,1

TO LEARN MORE

- To learn more on the Leclère (Leclerc) Family Fonds (P731)

- To learn more on the Clarence A. Gagnon Fonds (P116)

- To learn more on the Shared Emotions project

- To learn more on the Textual Archives Collection

NOTES

1. “Les Champs Elysées, ‘la plus belle avenue du monde’: histoire d’une expression,” France Info, April 10, 2019, (consulted November 15, 2019).

2. In fact, the Sainte-Chapelle was built under the reign of Louis IX (Saint Louis), in the 13th century.

3. H. Hazel Hahn, « Du flâneur au consommateur : spectacle et consommation sur les Grands Boulevards, 1840-1914 », Romantisme, 2006, no. 134, p. 69, (consulted November 18, 2019).

4. Hazel Hahn, Scenes of Parisian Modernity: Culture and Consumption in the Nineteenth Century, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, p. 45.

5. Ibid., p. 55.

6. Gilbert Wilson is probably referring to the restaurant La Coupole, another legendary Montparnasse establishment.

7. Manuel Charpy, “Les ateliers d’artistes et leurs voisinages. Espaces et scènes urbaines des modes bourgeoises à Paris entre 1830-1914,” Histoire Urbaine, 2009/3, no. 26, p. 50-51, (consulted November 18, 2019).

8. Elke Mettinger, Margarete Rubik and Jörg Türschmann, “Introduction,” Rive Gauche. Paris as a Site of Avant-Garde Art and Cultural Exchange in the 1920s, Leiden, Netherlands: Brill / Rodopi, 2010, p. 7.

9. Debora Carino, “Paris : Que savez-vous sur le quartier de Montparnasse ?” Figaroscope, August 4, 2017, (consulted November 18, 2019).

10. Marie Chantal Leblanc, Formation artistique et contexte social des peintres canadiens à Paris (1887-1895), M.A. Thesis (Art Studies), Université du Québec à Montréal, 2008, p. 28, (consulted November 18, 2019).

11. Letter from Maud Brown to Lucile Rodier Gagnon, January 23, 1942. Maud Brown is likely the wife of Eric Brown, former director of the National Gallery of Canada.

THANK YOU!

This project has been made possible in part by the financial support of Library and Archives Canada.