Île Sainte-Hélène: Before it was a public park

Discover the history of Île Sainte-Hélène before it became Montreal’s first public park, 150 years ago.

June 27, 2024

Although Île Sainte-Hélène is just one of the roughly 320 islands that make up the Hochelaga archipelago, its proximity to Montreal and the historical concentration of European settlement in the region have given it a special place in the hearts and minds of Montrealers. As the human presence in the area has altered over the centuries, the island has seen diverse occupants and been put to very different uses.

| Watch Mathieu Lapointe’s lecture during Festival d’Histoire de Montréal Discovering the history of Île Sainte-Hélène |

From indigenous territory to estate of the barons of Longueuil

Archeological excavations have shown that Indigenous people visited the island at least as early as the 13th century, long before the arrival of Europeans. The Saint Lawrence River, which the Haudenosaunee call “Kaniatarowanenneh,” was pivotal to the lives of the Iroquoian people Jacques Cartier encountered in the region during his 1535 expedition.

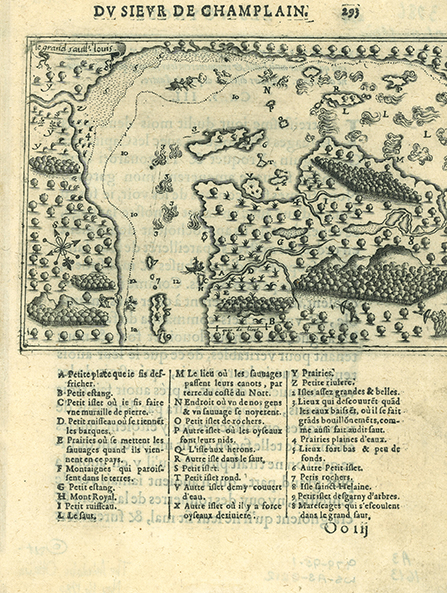

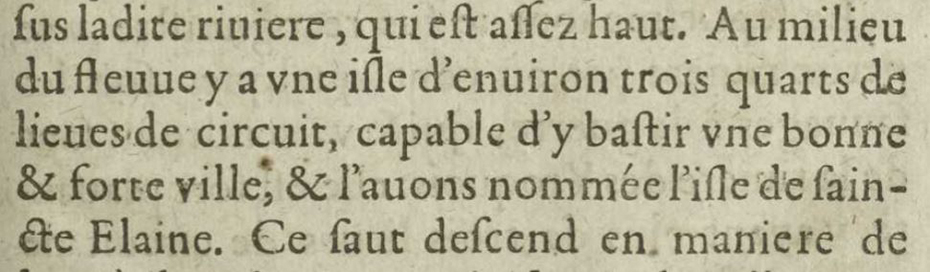

Although these Iroquoians seem to have dispersed by the time Champlain arrived, their descendants apparently continued to visit the region, which had become the object of territorial disputes between Indigenous nations. The Haudenosaunee, for example, clashed with the Innu and their Anishinabek allies from the Outaouais, with whom the French were allied. This partially explains the resistance encountered by the French when they began settling the Montreal area in the mid-17th century, which included several skirmishes on Île Sainte-Hélène – the French name given to the island by Champlain around 1611, in honour of his young wife Hélène Boullé.

In the 1660s the seigneury of Longueuil, which the French colonial authorities had configured to include the island, was granted to Charles Le Moyne (1626-1685), a key figure in the Montreal colony’s early years who was deeply involved in diplomacy and relations with Indigenous peoples, in times of both war and peace.

Elevated to a barony after the ennoblement of Le Moyne’s son, the seigneury would remain in the family of the barons of Longueuil throughout the French regime and for over half a century after the British conquest of 1760. During this period, the island was developed essentially as an agriculturally productive country estate. The land surrounding the manor house used by the barons as their summer residence, with its gardens and exotic trees, was leased to tenant farmers, and the power of the Sainte-Marie current, which runs between the island and Montreal, was harnessed to drive the flour mills that would play a major role in the region’s economy.

Because of this current and the island’s proximity to Montreal, it was also important strategically. In 1760 the Chevalier de Lévis set up the French forces’ final defences there before being obliged to concede defeat. During the American Revolutionary War, which began in 1775, the Americans succeeded in taking the island and arming it with canons, forcing Montreal to surrender.

1820-1870: A military island

Forty years later, in 1818, when Montreal’s fortifications had just been dismantled and another war with the United States had only recently ended, the British government purchased Île Sainte-Hélène and its neighbours, Île Ronde and Île aux Fraises, from a descendant of the Le Moyne family, Charles William Grant, with the aim of building a military complex. Several of its structures still remain, including the fort and the powder magazines. The Museum possesses a copy of the bill of sale signed by Governor Sherbrooke.

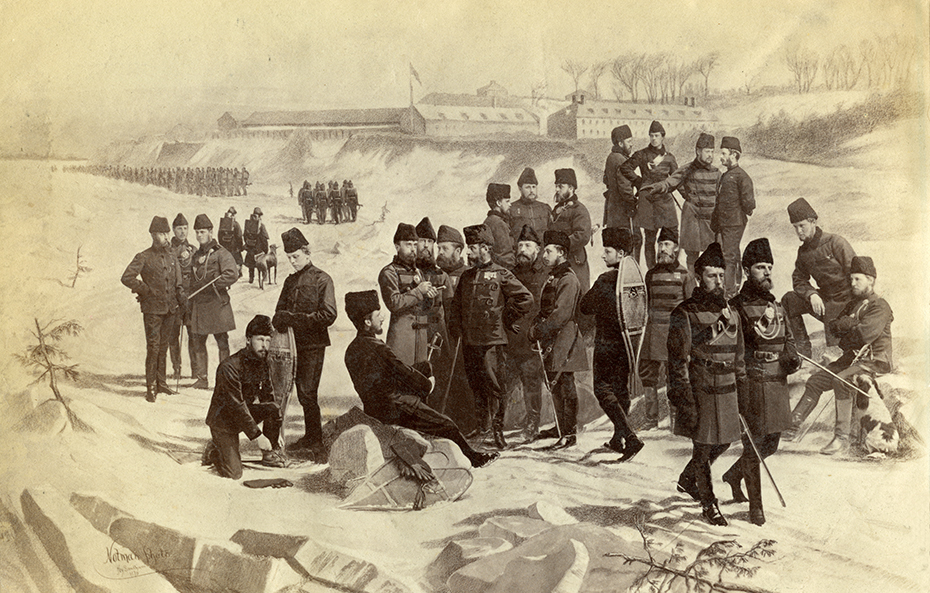

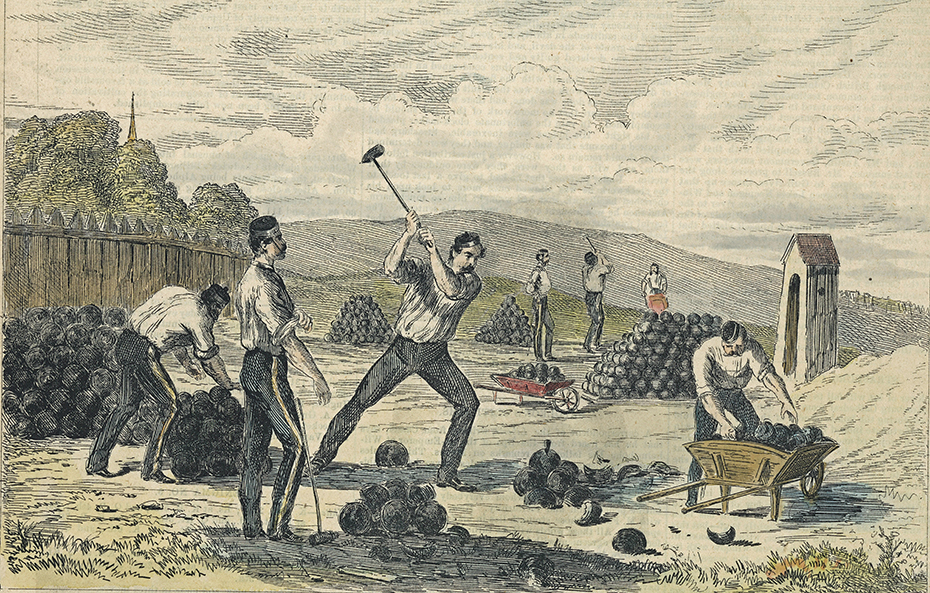

For the next 50 years activities on the island would be mostly military and security-related – the fort would actually serve briefly, between 1845 and 1848, as a military prison. Access to the island was restricted to a small company of soldiers and officers, along with their families, and a number of civilians providing various services. The famous Joe Beef ran the canteen there during the 1860s before opening his celebrated Montreal tavern.

Some islanders appreciated the relative isolation, so conducive to the romantic contemplation of nature. Among these were the officer Thomas Seaton and his wife, the watercolourist Phoebe Seaton, who while living on the island painted some wonderful landscapes and still lifes.

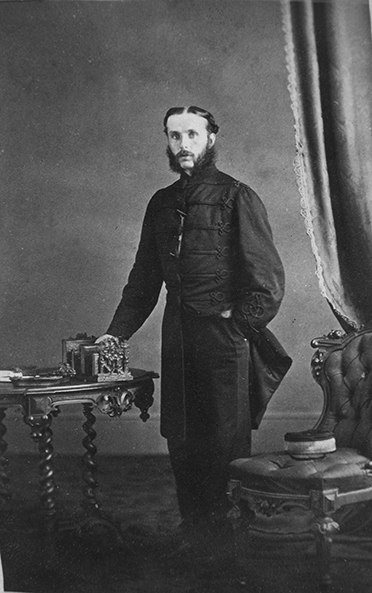

But as we learn from an amusing account given by artillery officer Francis Duncan (1836-1888), other military residents found the solitude hard to bear.

From military complex to public park

By the 1860s Great Britain was no longer willing to ensure the defence of its North American colonies, and this led to the Canadian Confederation of 1867. In 1870 the British army began withdrawing from its military installations on Île Sainte-Hélène, and the island was ceded to the federal government while continuing to serve as a training ground for militia and artillery troops.

This withdrawal represented a tremendous opportunity for City authorities of the time, whose plans included the creation of large urban parks: Mount Royal Park, a multi-year project, would finally open in May 1876. The year 1874 was decisive, for it was then that the City reached an agreement with the government to rent two large pieces of land formerly reserved for use by the army: Logan Farm, which would become Logan Park before being renamed La Fontaine Park in 1901, and Île Sainte-Hélène, which is now part of Jean-Drapeau Park.

| To learn more about the opening of the park, read the article 1874, opening of Île Sainte-Hélène Park |

In the latter case, the land was not ceded in its entirety: one sector was still reserved for military use by the federal government, which retained the right to reassume control of the island if necessary – which it in fact did during the 20th century’s two world wars. Maps from the period often show this division of the island into public park and “government reserve.”

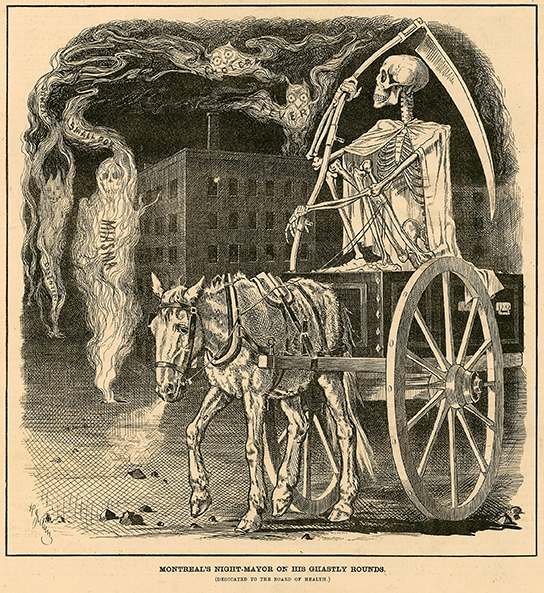

Parks to improve public health

As urban planner Jonathan Cha has explained in his dissertation on the history of Montreal’s parks, the opening of recreational outdoor spaces during this period was prompted by a growing awareness in Montreal – as elsewhere in the West – of the health problems associated with urban living. Owing to industrialization and mass migration, cities were growing at an exponential rate, resulting in serious health problems caused by overcrowding, insalubrious living conditions and inadequate infrastructures (drinking water supplies, sewer systems, etc.), particularly in working-class neighbourhoods. All these factors led to elevated death rates, which were higher in Montreal than in any other comparable Western city.

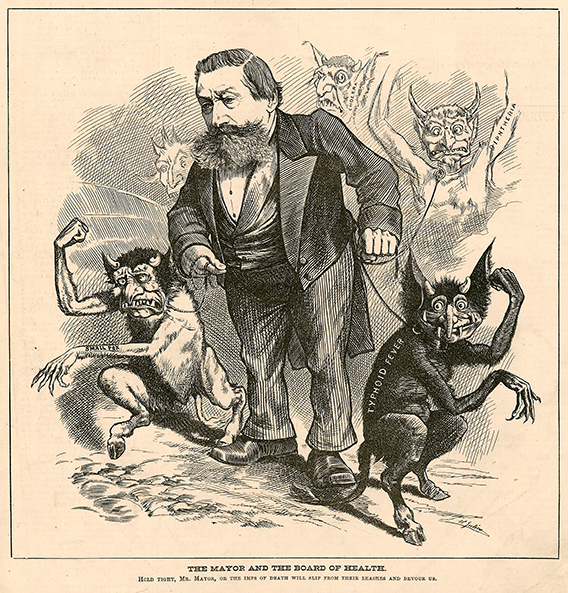

In 1866 a group of concerned political, economic and medical leaders founded the Montreal Sanitary Association, whose first president, businessman William Workman, would be elected mayor in 1868. Drawing inspiration from urban and health reforms introduced in England and France during the preceding decades, they turned their attention to the many problems affecting public health, particularly those related to water supply and sewage systems.

Another of their priorities was the provision of public parks, where inhabitants of the industrial city, with its overcrowding and pollution, could enjoy natural surroundings and breathe clean air. Emulating major European and American cities like London (Hyde Park), Paris (Bois de Boulogne, Bois de Vincennes), New York (Central Park) and Philadelphia (Fairmount Park), a number of Montreal politicians, including successive mayors – William Workman (1868-1871), Charles-Joseph Coursol (1871-1873) and Aldis Bernard (1873-1875) – devoted their efforts to making large green spaces part of the city map.

While it was assumed that Mount Royal Park, then in its final planning stages, would attract the middle-class residents of its affluent surrounding neighbourhoods, Île Sainte-Hélène was conceived from the outset as a leisure ground for those living in the working-class sectors running along the waterfront, in the “lower town.” According to historians Sarah Schmidt and Josée Desharnais, the simultaneous creation of these two large parks can be seen in a sense as a political compromise based on a principle of social segregation.1

Be that as it may, it was to general enthusiasm and considerable fanfare that Île Sainte-Hélène Park – Montreal’s first major public park – opened on June 24, 1874, Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day.

Notes

- Schmidt (1996), p. 50; Desharnais (1998), p. 43.

References

Cha, Jonathan. « Formes et sens des squares victoriens montréalais dans le contexte de développement de la métropole (1801-1914) ». Thèse de doctorat, Université du Québec à Montréal, INRS et Institut d’urbanisme de Paris, 2013. https://archipel.uqam.ca/6079/.

Daignault, Sylvain et Paul-Yvon Charlebois. L’île Sainte-Hélène avant l’Expo 67, Québec, Les Éditions GID, 2015.

Desharnais, Josée. « La gestion des loisirs publics à Montréal : l’exemple du parc de l’île Sainte-Hélène, 1874-1914 ». Mémoire de maîtrise (histoire), Université de Montréal, 1998.

Gervais, Diane et al. Deux îles, un parc, une ville… : le parc Jean-Drapeau, au cœur de l’histoire de Montréal, Montréal, Société du parc Jean-Drapeau, 2017.

Marsolais, Claude-V., Robert Comeau et Luc Desrochers. Histoire des maires de Montréal, Montréal, VLB, 1993.

Schmidt, Sarah. « Domesticating Parks and Mastering Playgrounds: Sexuality, Power and Place in Montreal, 1870-1930 ». Mémoire de maîtrise (histoire), Université McGill, 1996. https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/cc08hh62x.