Impersonating Indigeneity

How in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, “Indian” impersonations embodied stereotypes, reflecting cultural appropriation and erasure.

March 17, 2025

Of all the racialized impersonations that appeared at historically themed costume balls in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Canada, the majority portrayed Indigenous people.

Indigenous impersonations at these highly publicized social events warrant special scrutiny, and not just for the way they represent a distinct form of fictitious, racialized Other.

The prolific photographic documentation of these balls reveals a great deal about the material nature of these costumes, specifically the significant presence of actual Indigenous cultural belongings used for dress-up. Indigenous-made beaded and embroidered bags, moccasins, headdresses and hide garments appear in significant numbers.

Performing “Indianness”

While cultural appropriation in fashion and cross-cultural dressing are being explored in a growing body of scholarship, these concepts fail to fully express what was going on with the fancy dress “Indians” who appeared on Canadian rinks and in ballrooms. In a society with highly codified norms of gender, class, and religious and social boundaries, the fantastical and forbidden nature of performing “Indianness” offered multiple avenues of disruption, for both performer and audience.

Like others who engaged in cross-racial masquerade in fancy dress, those who portrayed “Indian” characters missed some of the opportunity to enhance their physical traits. Many wore wigs that would have been perceived as compromising to their attractiveness. Yet “redface” allowed some guests to imagine that darkened skin not only brought them closer to what a “full-blooded Indian” should look like, but also conferred some of the more romantically positive associations of stereotyped cultural attributes of Indigeneity.

Unlike characters dressed in blackface, Indigenous characters turned out for photographers in far greater numbers. The images taken by the Notman studio in Montreal and the Topley studio in Ottawa document ball and skating carnival costumes that incorporated Indigenous objects in these two locations from the early 1860s through the 1890s.

The particular ways in which these belongings are displayed in the images and the names or descriptions used in accounts of the balls also provide clues to what the wearers knew or believed about these objects.

Making myth

An example of the information provided by such portrayals is that of Charles-Frontenac Bouthillier who, at the 1865 Montreal Garrison fancy dress ball, appeared as the character of “Tecumseh,” the Shawnee warrior and chief (1768–1813) known mainly for his military exploits in the War of 1812 against the Americans.

In his photograph, Bouthillier is wearing a rare deer-horned headdress that is found in the Museum’s collection.

In the 1880s, a strikingly detailed costume assembled from Indigenous objects was worn by three different men for photographic portraits in three different studios, giving an indication of how it was circulated and valued.

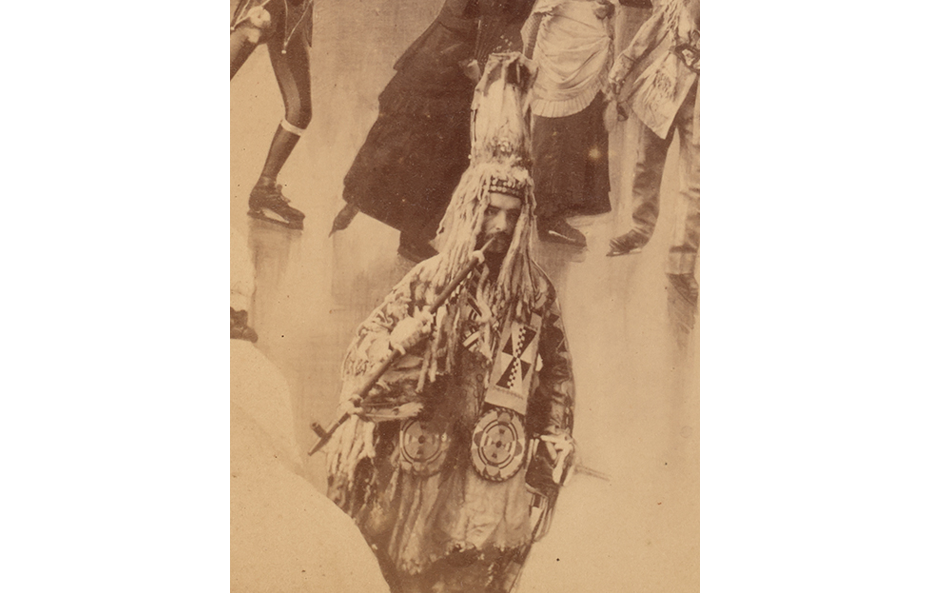

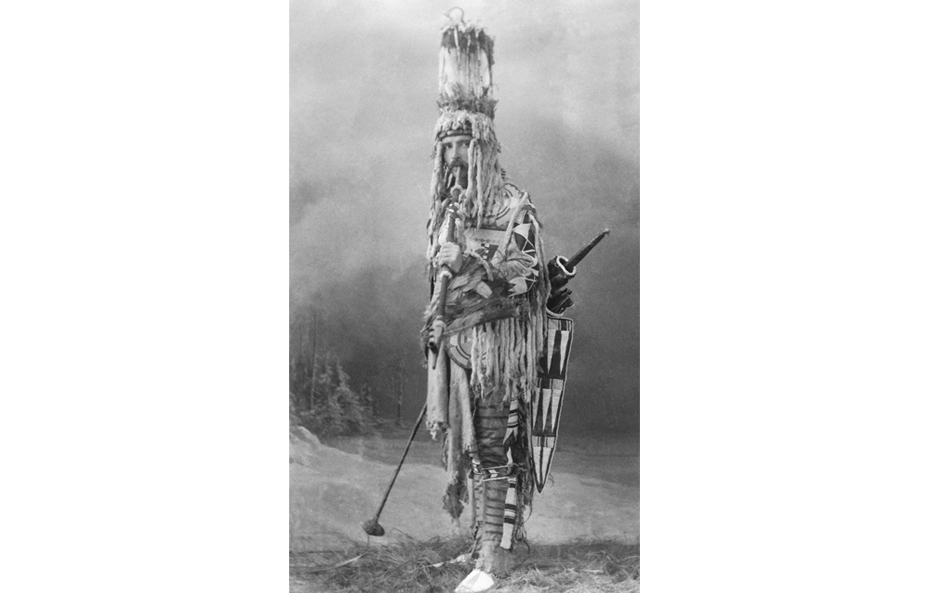

In 1881, the Notman studio in Ottawa took a head and torso view of Alexander P. Wright dressed as Lakota chief Sitting Bull, one of the most famous Indigenous leaders who resisted United States government policies for years, until his death in 1890. Wright’s portrait was later inserted in a composite photograph of the skating carnival at Ottawa’s Royal Rink.

Later that year in Montreal, Notman photographed Frederick Ayshford Wise wearing the exact same regalia, which includes a heavily beaded Plains shirt with ermine skins, a Siksika (Blackfoot) stand-up headdress, and leggings with horizontal black stripes known to represent the number of war expeditions the owner(s) participated in.

Again in Ottawa, in 1889 Wise’s son-in-law Sidney Smith posed for Topley dressed in the same outfit with the addition of a large beaded band of floral motifs across his forehead, for the carnival that opened the Rideau skating rink.

That all three men identified their character as “Sitting Bull” suggests that an origin myth relating to that chief was constructed for the costume. It is worthy of mention that its first appearance in 1881 coincided with the moment when Sitting Bull returned to the United States to surrender to authorities after being on the run in Canada for four years.

The Historical Fancy Dress Ball, Ottawa, 1896

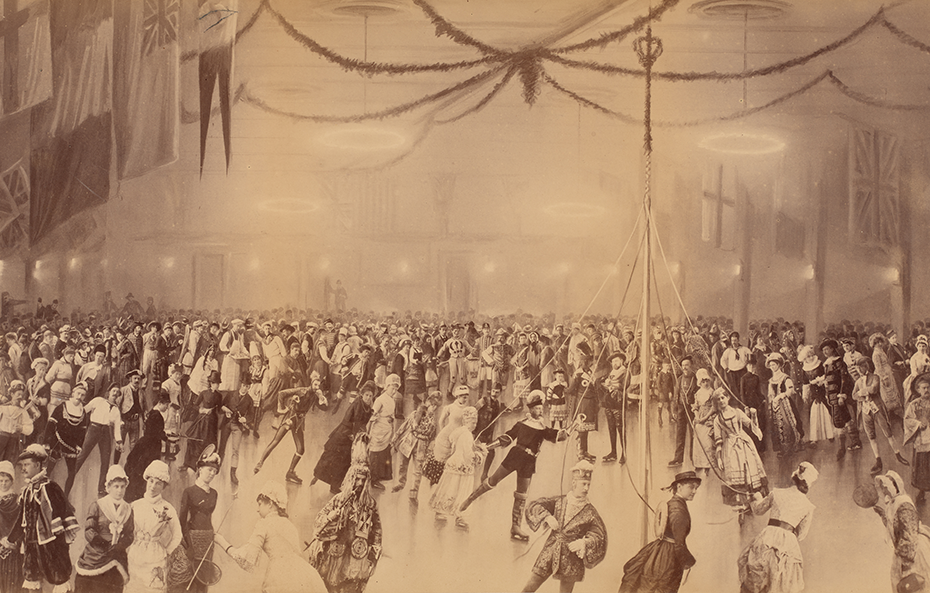

It was at the 1896 Historical Fancy Dress Ball in Ottawa organized by Lady Aberdeen that the greatest number of Indigenous impersonations appeared at a single event.

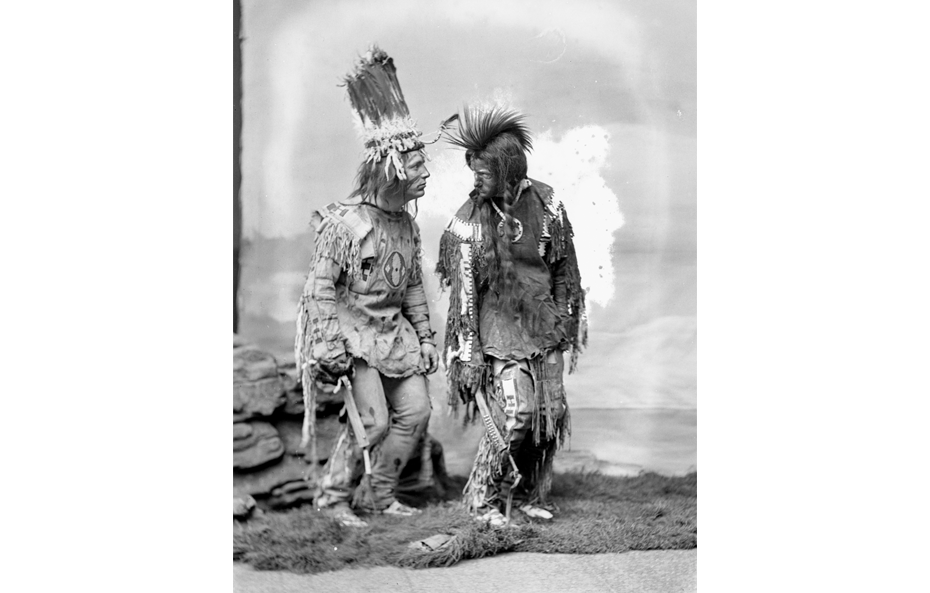

Hayter Reed, Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, who took centre stage at the ball claiming to portray “Donnacona, chief of Stadacona Indians whom Cartier carried off to France,” posed for a studio photograph with his stepson Jack Lowrey as “Seaudawate, Iroquois child taken captive by the Mohawks”. Their costumes, pastiches of Indigenous belongings and fancy-dress bricolage, reveal fictions inspired by Pan-Indianism rather than any sort of striving for ethnographic correctness.

At the ball, an unexpected event occurred. According to the formal account published in the souvenir book, “the Indians that had taken part in the various historic groups formed themselves into a separate body, and marched to the front […]. Mr. Hayter Reed […] made a speech in Cree, with all the guttural articulations appropriate on such occasions, and Mr. Wilfred Campbell, as “Tessouat,” acted as interpreter.

Reed, who worked in the Department of the Interior for sixteen years and was Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs from 1893 to 1897, had extensive personal knowledge of the circumstances of Indigenous peoples, which made him feel entitled to represent an Indigenous chief and have onlookers find it credible

The Indigenous reality that Reed knew—and worked to keep in place—was one far different from that of the “noble savage” that he portrayed. Reed had been responsible for some of the most notorious iniquities in colonial policy, including the “pass system” and peasant farming conditions on reserves, both intended to control and restrict Indigenous peoples and their access to their livelihoods. Using schools as a tool to assimilate Indigenous people, enforcing the strict application of the Department’s work-for-rations policy, refusing extra rations of food and supplies when crops failed, and insisting that the hangings of Indigenous people be forcibly observed by their relatives, including children, as a lesson to be learned, Reed earned the nickname “Iron Heart” from those living under the yoke of his legal and political pressures.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, burdened by legal, political, and economic constraints, Indigenous people slowly withdrew from the body politic. Reed and other colonial representatives were responsible for this disappearance, both real and symbolic. At that time Indigenous people were visible only when settlers appropriated their image.

From fetishized trophies to revitalization

Parading Indigenous cultural belongings on an ice rink or ballroom floor was tantamount to showing them off as trophies, proof of the success of their political endeavours. The use of Indigenous cultural belongings at historically themed balls helped consolidate the idea of Indigenous people as belonging to the past—simultaneously Other and historical.

By caricaturing them, ball-goers illustrated the benefits of the long era of colonization and the strength of belonging to the Empire, whose doctrines of progress ensured that the Indigenous threat constructed in the colonial mindset was safely relegated to the past.

The story told by these fancy dress balls is a sad and difficult one from an Indigenous perspective: appropriation, dispossession, exclusion and oppression are common themes that emerge from this narrative. Ironically, the period portraits of the people who impersonated and appropriated Indigeneity allow us to better understand the origins and provenance of some of these belongings today. Indeed, photographs are often very helpful in tracing object biographies. In many instances, the thorough treatments conducted by professional conservators can restore the original appearance, grace and dignity of objects, before they were damaged by mishandling.

Now that these belongings are known, preserved and accessible to Indigenous people, they are no longer invisible. Evoking pride, agency and resilience, they can again be used to express and reassert the vitality of Indigenous cultures.

—

The full version of this essay was published in Costume Balls: Dressing Up History, 1870–1927, edited by Cynthia Cooper.