The Joy and Agonies of late-19th century Courtship

Experience the highs and lows of young Henri Gaspard Le Moine as he tries his best to court the lovely Emma Renaud.

February 9, 2020

This series of 12 articles written for the Shared Emotions project uncovers feelings, sensations and values buried in archival documents and looks at how they are shaped by the cultural and historical context of the time.

______

“I am slowly daring to believe that she loves me, although I do hope that I am justified in convincing myself of such a thing because I would be very unhappy if I later learned it was not true.”

(January 25, 1871)

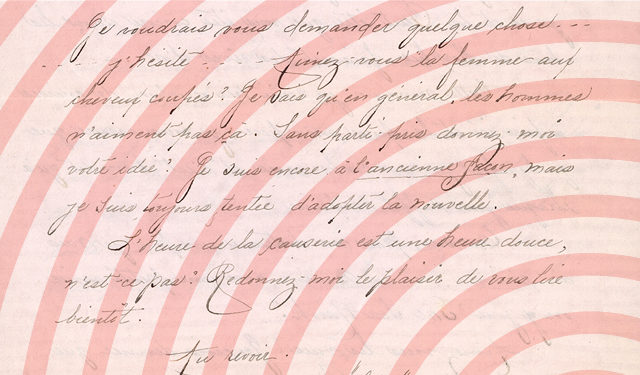

Expressing both hope and anxiety, this passage from the diary of Henri Gaspard Le Moine evokes the myriad emotions that accompany the blossoming of a love whose outcome remains uncertain. With the approach of Valentine’s Day, we can appreciate the deep, private thoughts of young Le Moine as he writes a daily record of his evolving relationship with Emma Renaud. Having returned to his home town in 1867 after studying at Collège Sainte-Marie de Montréal followed by two years of school in New York, Henri Gaspard began courting the daughter of Jean-Baptiste Renaud, a prominent Quebec City merchant. His journal is a precious chronicle of his feelings as he navigates the rules and rituals of courtship.

COURTING: A JOURNEY FRAUGHT WITH DIFFICULTIES

Henri Gaspard was 22 years old when he wrote these lines. He had the opportunity to see the lovely Emma almost daily at social gatherings hosted by the Renaud family. He was sometimes accompanied by his father, who enjoyed spending time with Emma’s father. The two families saw each other often and moved in the same circles. In the late 19th century, young people of marriageable age were usually introduced by family members, relatives, neighbours and friends1. In this way, without having to impose a choice, parents could ensure that their daughter’s chosen companion would come from a respectable family and be able to provide for the one he intended to start.

As a result, Henri Gaspard and Emma would usually meet in the Renauds’ home, under the attentive supervision of their respective families. Other than these get-togethers, Henri Gaspard would spend time with Emma on social visits, at afternoon teas and on walks along the ramparts of Quebec City, where they would cross paths with other young people they knew. Through the young man’s journal entries, the reader becomes acquainted with an extended social network within which future alliances will be forged.

At the time, young people of marrying age quite often took an interest in who was seeing whom. In fact, such musings are frequently found in mid-19th century writings2. In his journal, Henri Gaspard recounts how he helped his friend Henri Bossé gain an introduction to the family of a young woman, something that would have been unthinkable without the assistance of a shared acquaintance.

“Bossé asked me to spend the evening with him at Laure’s home. He’s going to give it a try. When I asked Emma about it, she suggested I do him this favour, noting that Laure might like him.”

(October 23, 1870)

However, several weeks later, Henri Gaspard quotes Emma as saying that, unfortunately, his friend’s attempts did not seem to be achieving the desired result:

“She told me that when she asked Laure what she thought of Henri Bossé, whether he was clever, Laure responded that he was like his sister Minnie, he only talked about himself and his family. I thus fear Bossé has missed his chance, so I will no longer get involved.”

(November 28, 1870)

Young Henri Gaspard’s primary concern is, after all, his relationship with Emma. His beloved’s moods, which he does not always understand, sometimes torment him, as illustrated in this account of an evening at the Renaud home:

“We talked about many different things. But when I was leaving, Emma said that she was not happy with me, that I had said something that annoyed her. I couldn’t figure out what it was. It really upsets me when she makes me afraid that I have displeased her.”

(October 16, 1870)

As it turns out, poor Henri Gaspard has to wait until the following day to uncover the problem. He is confused by the vigilance required during the courting process:

“After a lot of effort, I finally found out […] that Emma was annoyed because I had contradicted her. I had earlier said that Minnie Bossé and Balthasar Langevin’s wedding was very extraordinary, and then I later contradicted her, remarking that it was nothing special. I promised her that I would never contradict her again, ever. But I felt the blood rush to my head when she told me that. Always agree with her.”

(October 17, 1870)

During the five-year courtship leading to their wedding, Emma and Henri Gaspard’s relationship sometimes put him through an emotional roller coaster. His uneasiness became even more pronounced when the lovely Emma, after making her social debut in the fall of 1870, began attending more society events where she was likely to meet other young men. Henri Gaspard recounts this anecdote about the appearance of a potential rival at a party.

“At one point I thought I was actually going to be sick. I felt so hot my head was going to explode and I could feel my blood boiling in my veins. Emma had spent the entire evening with Jean Blanchet; there was nothing I could do. If Jean B. wouldn’t leave her side, it wasn’t her fault. They seemed to be having a wonderful time together but there was nothing wrong with that. However, shortly before supper I went up to speak to her, saying, “Didn’t you promise to go down to supper with me?” […] To which she answered a very curt “No,” in a tone that froze my heart. Then she turned back to Blanchet and continued talking with him”

(December 8, 1870)

Several months later, a quarrel about a promised dance at the Bachelors’ ball once again throws Henri Gaspard into emotional turmoil. In the privacy of his journal, he expresses an anguish that would be difficult for him to otherwise articulate because it would appear unseemly in a young man expected to maintain at all times a respectful attitude towards the young woman he is courting3.

“Instead of going to bed, I [am staying up], suffering. I [want] to put my ideas down on paper so I can revisit them later, as it is currently impossible for me to think clearly. My whole body is shaking; it’s as if a terrible chill is freezing me to the very marrow; my arms and legs are throbbing with the racing palpitations of my heart. I am in love. Ah! Now I know what it is like to love someone. Love, they say it’s bliss—but not on earth. Love for me is always mixed with fear, and it seems as if Emma wants to prevent me from being happy and [heighten] these fears by denying me the thousand little things that would make a sensitive soul happy. Ah! If only she could put herself in my shoes. But some souls are colder than others, and Emma seems to be driven by her own ego […]”

(February 14, 1871)

With all the uncertainties it entails, courtship appears to threaten the self-esteem of the young people obliged to engage in it, making them very vulnerable4. A necessary evil at a time when there were few avenues outside marriage, it does seem to be the price one has to pay for the great joys of a love that, slowly, reveals itself with time.

“Finally. Emma has admitted it, she has said that she loves me. I can now be certain of my happiness. I hadn’t dared believe, and now I do. I spent most of the afternoon with her, and this evening we talked about the past and things like my trip to see her in Kamouraska. She told me that, back then, she enjoyed seeing me as her suitor but didn’t really care for me, she didn’t love me. But today, today she says that it’s different. […] I love her madly too and I have always loved her, ever since we met, but I love her more than ever. I’m going to bed now, to dream that Emma loves me, but now it is no longer a dream.”

(March 11, 1871)

TO LEARN MORE

- To learn more on the Le Moine Family Fonds (P761)

- To learn more on the Shared Emotions project

- To learn more on the Textual Archives Collection

NOTES

1. Françoise Noël, Family Life and Sociability in Upper and Lower Canada, 1780-1870: A View from Diaries and Family Correspondence, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003, p. 20.

2. Peter Ward, Courtship, Love, and Marriage in Nineteenth-Century English Canada, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990, p. 137.

3. Sonya Roy, Les règles du jeu de la séduction dans les manuels de savoir-vivre québécois (1863-1917) : investir le monde du sentiment et de l’intimité masculine, mémoire de M.A. (histoire), Université de Montréal, 2006, p. 98-99, (consulted January 8, 2020).

4. Peter Ward, Courtship, Love, and Marriage in Nineteenth-Century English Canada, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990, p. 163.

THANK YOU!

This project has been made possible in part by the financial support of Library and Archives Canada.