The Joys and Woes of Unpredictable Winter

The Museum’s archives chronicle the emotions felt by Quebeckers as they faced the vagaries of winter in centuries past.

March 21, 2024

This series of 12 articles written for the Shared Emotions project uncovers feelings, sensations and values buried in archival documents and looks at how they are shaped by the cultural and historical context of the time.

______

“My country isn’t a country, it’s winter!” sings poet Gilles Vigneault. For centuries, or indeed millennia, the powerful presence of winter has forced the people living in this country to make adjustments to the way they live every year. A physical and psychological imposition, winter affects their emotional lives, as demonstrated in numerous archival documents preserved in the McCord Stewart Museum’s collections.

Memorable blizzards and disruptive thaws

Chronicles of days gone by, diaries contain many references to the weather, both ordinary and unusual atmospheric phenomena. The writers seem to want to preserve a trace of the events that have a profound effect on everyday life during the winter, events that will otherwise inevitably fade from memory. Incidentally, these types of documents are becoming increasingly popular with historians who want to write, in the words of Alain Corbin, “a history of how weather has shaped the human experience.”

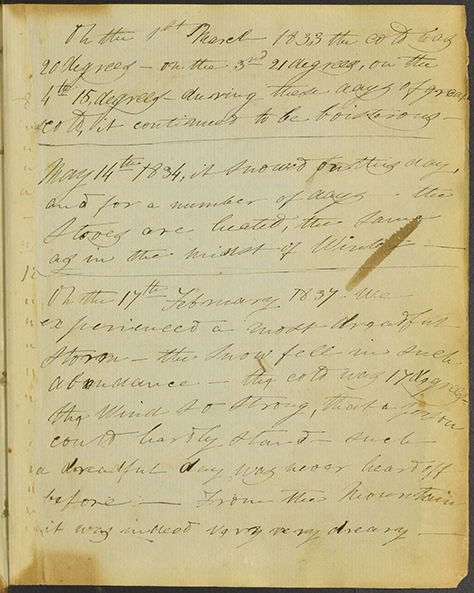

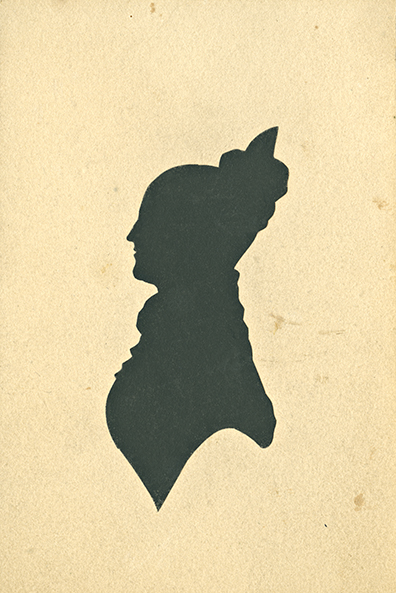

In the first volume of the diary she kept for over thirty years, Marie-Angélique Hay Des Rivières (1805-1875), wife of Henri Desrivières (c. 1805-1865), reported a series of remarkable weather-related events, starting in the year 1833.

In the year 1834, for example, she noted: “May 14th 1834, it snowed on this day, and for a number of days – the stoves are heated, the same as in the midst of Winter.”

The following weather-related entry documents another memorable storm three years later, witnessed from Mount Royal.1

On the 17th February 1837, we experienced a most dreadful storm – the snow fell in such abundance – the cold was 17 degrees – the wind so strong, that a person could hardly stand – such a dreadful day was never heard off [sic] before – From the mountain it was indeed very very dreary.

M2012.63.1.1 (p.3), P752

Conversely, Marie-Angélique recorded an unusual thaw in January 1838, which disrupted the usual winter modes of transportation:

January 1838 – 8th, extraordinary weather for the season – the river is as free as in the summer, continued rain for a number of days – a gentleman drove in his go cart yesterday – the roads are very bad for sleighing – the boats and canoes, cross as easily as in the midst of Summer.

M2012.63.1.1 (p. 9)

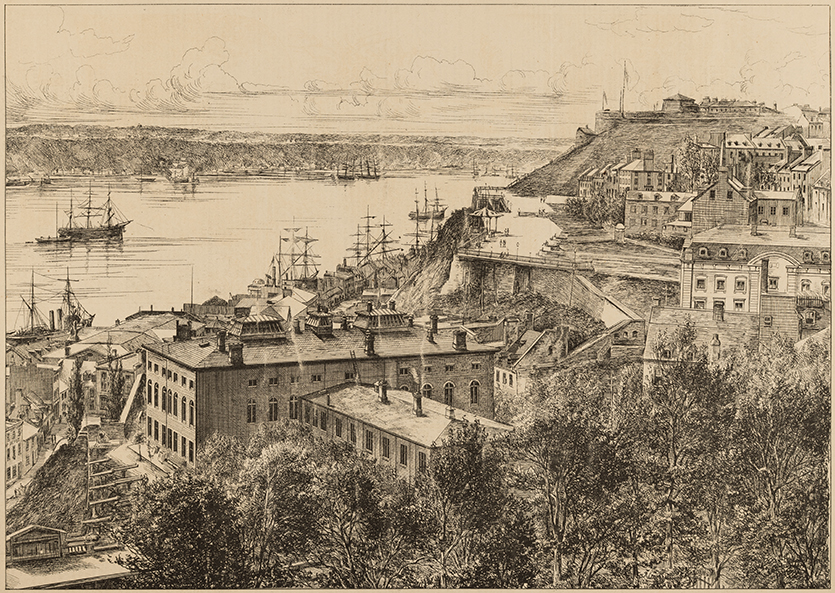

A student's weather reports

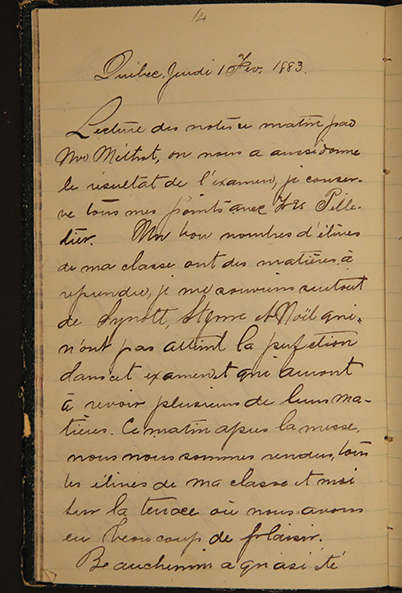

Forty-five years later in 1883, young Louis-Alexandre Taschereau (1867-1952), the future Premier of Quebec, also noted climate events in the diary he kept while studying at the Petit Séminaire in Quebec City. The weather appears to have offered him some fun and adventure, unlike his routine of constant study, which included attending mass, translating from French to Latin and Latin to French, and taking exams. For example, the 15-year-old describes the pleasure of playing on the Dufferin Terrace with his classmates after a snowfall:

February 1, 1883: This morning after Mass, my fellow students and I all went to the terrace where we had a lot of fun. Beauchemin almost got knocked out by the snow! [translation]

M2004.13.1 (Part 1, p.19), P632

The heir to a seigneurial family in the Beauce region south of Quebec City, Taschereau noted in the following days that the intense cold and snow had led to the creation of an ice bridge over the St. Lawrence River. According to historian Jean Provencher, ice bridges greatly facilitated communications during the winter, as well as economic exchanges between the two sides of the river.2

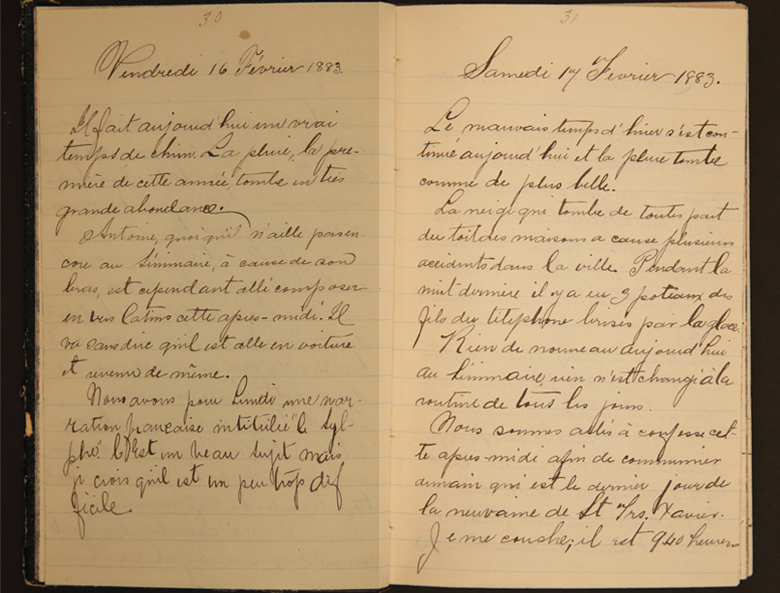

However, a mid-February thaw spoiled everything. Heavy rains melted snow off roofs and caused accidents, and even threatened a modern infrastructure that had been brought to Quebec City just three years earlier: the telephone.3

Friday, February 16, 1883: It’s raining cats and dogs today. It’s the first rain of the new year, and it’s absolutely pouring.

Saturday, February 17: Yesterday’s bad weather continued today with even more rain. Snow’s falling off roofs everywhere, causing accidents across the city. Last night, 3 telephone poles were broken by ice. [translation]

M2004.13.1 (Part 1, p. 35-36), P632

Seasonal illnesses and home remedies

Jean Provencher describes what people living in Quebec’s St. Lawrence River Valley during the 19th century would do to get through the cold season: “The home became the centre of the world. Life took place indoors. […] The stove would be heating constantly. Or even overheating.” Back then, like now, this confinement would have an impact on the physical and psychological well-being of those wintering.

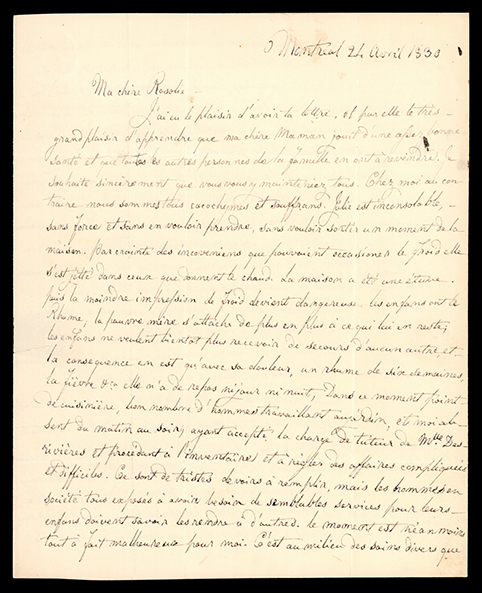

In an April 1830 letter sent to his sister Marie-Rosalie Papineau Dessaulles (1788-1857) in Montreal, Louis-Joseph Papineau (1786-1871) expressed his delight at learning that his mother and the rest of the family were in good health. Unfortunately, in his case, the news was not as good:

In our home, on the contrary, we’re all suffering from the doldrums.4 Julie is a wreck—she has no energy, doesn’t seem to want to get better, and doesn’t even want to step outside. Afraid of the discomforts caused by cold, she has instead embraced those caused by heat. The house has been kept as hot as an oven and the slightest hint of cold is seen as dangerous. All the children have a cold, their poor mother is increasingly attached to those still living, so the children will soon no longer accept care from anyone else. The upshot is that, between her pain, a six-week cold, and fever [?], she has had no rest, day or night. At the moment we have no cook, many men working in the garden, and I’m away from morning to evening, having agreed to be Miss Desrivières’ guardian and carrying out an inventory to settle some complicated and difficult matters.5[translation]

P010/A4,3 (p. 43)

A look at Marie-Angélique Hay Des Rivières’ diary reveals that it was sometimes used as a health record, tracking the various diseases afflicting her children.

Henry, Frobisher, and Theodore had the measles in February 1837

[…]

Henry & Frobisher had the scarlet fever in June 1837

Theodore was also taken with it. They all three had it very slightly

M2012.63.1.1 (p.5-6)

It also recorded a vaccination, a procedure she still found somewhat novel, given that she underlined the word:

On the 2nd April 1839 my dear babe Francis Henry was vaccinated, it took immediately, and proved very good, the vaccine came from Mrs de Rocheblave’s fine boy – 15 months old.

M2012.63.1.1 (p. 12)

However, traditional remedies appear to have been the more popular choice for dealing with the maladies brought on by winter, particularly in rural areas. In a letter sent from Petite-Nation to her father Denis-Benjamin Papineau (1789-1854) on November 18, 1846, young Julie-Séraphine-Aurélie Papineau (1830-1926) mentions applying mutton tallow to a sick child’s chest:

Little Godefroy has had a very bad cold of late; we were very worried last night because he had difficulty breathing so we put mutton tallow on his chest. This morning he’s a lot better although still a little short of breath. [translation]

P010/B4 (p. 64-67)

Likewise, Provencher’s book includes a recipe published in the Gazette des campagnes in December 1875 that uses raw beef marrow, veal kidney fat, honey, olive oil and camphor to make an ointment for chapped hands.

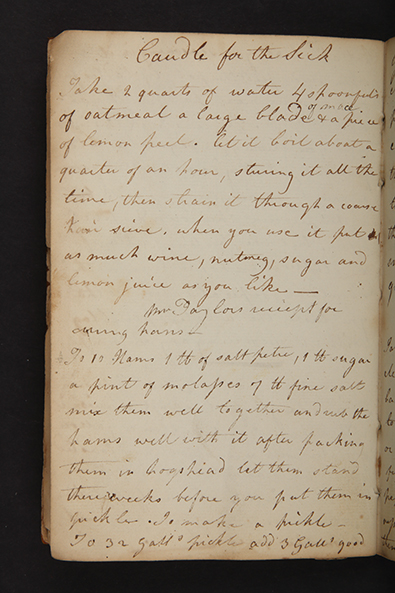

Old cookbooks often contain this type of home remedy. Anne Emily Rush (1779-1850), the daughter of a signer of the American Declaration of Independence, moved to Lower Canada after her Philadelphia wedding to George Ross Cuthbert (1776-1861), seigneur of Lanoraie and d’Autray. Her collection of recipes, dated about 1801, contains a recipe for a “Caudle for the sick,” a drink usually made with warm wine or ale mixed with bread or oatmeal, eggs, sugar and spices, intended to nourish and speed the recovery of the sick.

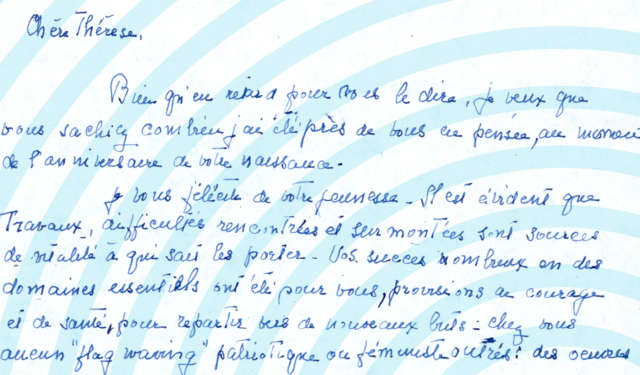

Winter eventually comes to an end

After all the hardships of the long winter months, spring eventually arrives, with its freshness and sense of rebirth and renewal. Following the litany quoted above in his letter, Louis-Joseph Papineau reveals that he is already thinking about gardening. His sister Rosalie had apparently asked him to buy her some trees in the city, and the next page of his letter is filled with his detailed explanations, in a somewhat paternalistic tone, of his choices and the trees that he is sending her (P010/A4.3, part 1, p. 44).

As for young Taschereau, several days after witnessing the April 19, 1883, fire that ravaged the Parliament building on Côte de la Montagne6—with some fellow students apparently disappointed that the Seminary was not affected by the flames—he had an opportunity to witness a completely different type of show on April 23 that heralded the coming of spring:

The ice bridge over the river so eagerly anticipated last fall is gone this morning, much to everyone’s delight. I went down to Lower Town to watch the ice floes go by. [translation]

M2004.13.1, (Part 1, p. 103)

Finally, life can begin again…

Notes

- It is not clear whether Marie-Angélique wrote these words from Burnside, the estate of James McGill and site of the future McGill University at the foot of Mount Royal, which her husband Henri had inherited through his father. It is thought that the Desrivières had moved away some time earlier, and were perhaps living at the neighbouring estate owned by their relative, James McGill Desrivières.

- Provencher, Les quatre saisons…, p. 525-539. See the full list of the works cited at the end of the article.

- https://www.journaldequebec.com/2018/09/25/photos-voici-la-petite-histoire-du-telephone-a-quebec

- Doldrums: A spell of listlessness or despondency; low spirits. (Merriam-Webster)

- Papineau was settling the estate of James McGill’s heir, François-Amable Trottier Desrivières (1764-1830), who had hired him to fight the claims of the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning, which wished to establish McGill University: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/desrivieres_francois_6E.html

- https://www.assnat.qc.ca/fr/visiteurs/parlement/parlement-1792.html

References

Corbin, Alain. “Pour une histoire de la sensibilité au temps qu’il fait” in Dix ans d’histoire culturelle, É. Cohen, P. Goetschel, L. Martin and P. Ory (eds.) (Villeurbanne: Presses de l’Enssib, 2011) 82-100. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pressesenssib.1011

Corbin, Alain (ed.). La pluie, le soleil et le vent. Une histoire de la sensibilité au temps qu’il fait (Paris: Aubier, 2013).

Provencher, Jean. Les Quatre Saisons dans la vallée du Saint-Laurent (Montreal: Boréal, 1996), p. 411; 419.