Little Burgundy: Home to jazz, history, and science for motivated girls

A neighbourhood where jazz enlivens the walls, murals convey history, and science inspires girls.

February 18, 2025

My first encounter with Little Burgundy

On a Wednesday like any other—well, almost any other—I headed to Les Scientifines, an organization with an infectious energy that promotes science to young girls, many of whom are of African descent. My daughter wanted to learn more about volcanoes, and I wanted to understand why the neighbourhood was so full of history and jazz. When we arrived at the Oliver Jones community centre, which houses Les Scientifines, I was immediately hooked. Yes, that Oliver Jones, the jazz great. In this place, even the walls sing.

A neighbourhood vibrating with history

Little Burgundy is much more than a Montreal neighbourhood. It is what is known as a Black space—a place where the history, culture and artistic output of Black communities come to life, take a stand and assert themselves. It all started in the late 19th century, when sleeping car porters arrived from the United States and the Caribbean. These Black workers, poorly paid but well respected, laid the foundation for a close-knit community.

However, it was often their wives and other neighbourhood women who started social and cultural institutions. The Coloured Women’s Club of Montreal, founded in 1902, became a mainstay of community support. Figures like Daisy Peterson Sweeney shaped the area’s cultural history by training generations of musicians.

There was also a chapter of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), founded by activist Marcus Garvey in which women played a key role. This activist organization advocated for the empowerment of people of African descent long before it became a globally recognized right. And of course, there was jazz, everywhere. Oscar Peterson learned his scales there, and Oliver Jones developed his solos. Bar and jazz club Rockhead’s Paradise was the place where music would break down racial barriers, at least for a night.

Murals and history

Every wall has something to say. For example, there is a mural dedicated to Daisy Peterson Sweeney, a legendary music teacher and leading developer of young Black talent, along with Jazz Born Here, a vibrant tribute to Oscar Peterson that illustrates Little Burgundy’s cultural impact. These murals embody the concept of Black space; visible reminders of often forgotten, often marginalized stories, they depict a collective memory of the Black community in a constantly changing urban context. They do not merely decorate the street; they reaffirm the right to exist, to remember and to have a voice.

During his 1990 visit to Montreal, Nelson Mandela reiterated that freedom is meaningless without social justice. This message echoes the history of Little Burgundy, which continues to symbolize the fight for acknowledgment and inclusion. The mural that pays homage to him is part of this ongoing fight of resistance and hope.

Organizations on the pulse of the community

Les Scientifines, DESTA Black Youth Network and Harambec continue to write the neighbourhood’s collective history. Les Scientifines offers young girls a space to explore science without stereotypes, DESTA supports young Black adults in reaching their educational and professional goals, while Harambec advocates for the empowerment of Black women. These organizations are bastions of contemporary Black space, where future generations can imagine, create and assert their place in the city.

Building the future: Diverse Pasts and Near Futures

The living history of Little Burgundy is also inspiring new generations to reimagine their environment. Diverse Pasts and Near Futures, a youth program from the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), aims to increase accessibility to architectural education and museum spaces for BIPOC youth.

In 2024, a pioneering workshop, Reimagining Community Architecture, was held at the CÉDA in Little Burgundy. Using the history of the Negro Community Centre (NCC) as a springboard, young participants were invited to imagine an active, inclusive community space and examine how architecture can reflect as well as transform the needs of a community. With activities that combine hip-hop and urban space or use mapping to better understand neighbourhood experiences, this program is a direct response to the need of historically marginalized communities to reappropriate urban space.

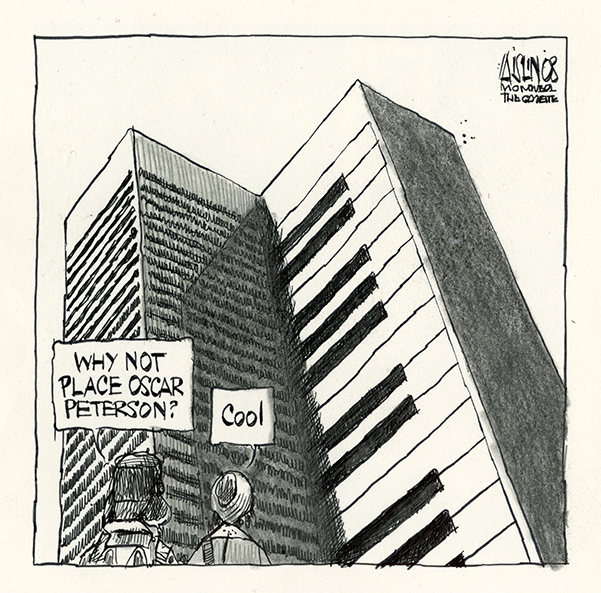

A pressing question: What about toponymy?

For all its strengths, the neighbourhood still lacks any streets or metro stations named for an iconic Black figure like Daisy Peterson Sweeney, Oscar Peterson or Oliver Jones. Why should people have to content themselves with short-lived artistic tributes when the collective Black memory, particularly that of women, deserves a permanent visible mark on the urban landscape? Toponymy is not just an assortment of trivial names—it is a political gesture. Renaming a street, a station or a space is a way of saying: “This history is important; it deserves to be etched into the collective memory.”

Why all this is important

Little Burgundy is much more than a Montreal neighbourhood: it is a living symbol of Black resilience, creativity and history. In a city where mainstream narratives can erase the traces of marginalized communities, this neighbourhood remains a place of cultural resistance and identity affirmation. By embodying the concept of a Black space, Little Burgundy invites us to reflect on a city where each space tells a story, where there is room for multiple memories and where diverse identities are celebrated. One thing is certain: this neighbourhood has things to say as well as questions to ask.

With thanks to Leslie Touré Kapo for reviewing this article.