Miss Lily, a role model of femininity

Discover the story behind a 19th-century fashion doll. Before Barbie, there was Lily.

The doll is one of the most imperious needs and, at the same time, one of the most charming instincts, of feminine childhood. To care for, to clothe, to deck, to dress, to undress, to redress, to teach, […] to imagine that something is someone—therein lies the whole woman’s future. While dreaming and chattering, making tiny outfits, and baby clothes, […] the child grows into a young girl, the young girl into a big girl, the big girl into a woman.1

–Victor Hugo, Les Misérables, 1862

As part of its holdings, the McCord Stewart Museum is proud to include over 700 dolls, a collection that spans some 200 years of history. Of this impressive number, one in particular stands out for its provenance, its story, its extensive trousseau of over 300 accessories, and its social significance.

Beneath her frivolous appearance, this doll, named Miss Lily Darboy by her owner, plays a more subtle educational role that harkens back to the words of Victor Hugo. Embodying the feminine ideals of her time, she is a role model of the virtues that society in general, and her social class in particular, expected of women.

Fashion dolls

Lily is what is known as a fashion doll, a title that describes a long line of dolls going back more than 500 years. Introduced in the late 16th century, fashion dolls, who could be male or female, were initially designed for adults. Wearing clothing, head-coverings and accessories in the latest French fashions, these representatives were sent out to be exhibited in all the European courts. Although fashion dolls seemed to disappear in the late 18th century, they made a comeback under the Second Empire (1852-1870) as objects of a privileged childhood, serving the needs of fashion, domestic education2 and consumerism.

In fact, despite the 19th-century boom in doll production, fashion dolls, popular between 1860 and 1890, remained a luxury toy for most families, even the wealthy.3 In 1874, a doll like Lily could cost up to twenty American dollars—a significant sum at the time4—and that did not include the clothing and extravagant accessories that could be found in Paris specialty shops.5

Édouard Fournier wrote about fashion dolls in his 1889 book Histoire des jouets et des jeux d’enfants [History of Children’s Toys and Games]: “One would hardly suspect that Paris is home to an entire world of fashion designers, linen sellers, milliners, shoemakers, florists and wigmakers catering solely to dolls; businesses employing thirty or more workers focus exclusively on making dresses, pinafores, etc., for these little darlings.”6 Miss Lily is a perfect example of this.

Lily and her parisian background

Purchased in Paris around 1863 by Monsignor Georges Darboy, Archbishop of Paris,7 Miss Lily was given to his niece and goddaughter Marie Eugénie Ida Darboy (1850-1927), the daughter of Élie Jean Baptiste Darboy, a judge at the Nancy commercial court, and Madeleine Eugénie Batail. Marie received the doll when she was 13 years old, a transitional age between childhood and adulthood.

Although the doll’s body bears no manufacturer’s name, the name Lily suggests that she came from À la poupée de Nuremberg, the shop of Madame Jeanne Lavallée-Péronneon Choiseul Street in Paris. Lily was Madame Lavallée-Péronne’s signature doll. A survey of various museum and private collections reveals the existence of Lily dolls with a variety of faces and bodies, indicating that Miss Lily is more likely a generic doll sold at Madame Lavallée-Péronne’s shop than a specific doll. Rather than making dolls herself, she would buy ready-made dolls from manufacturers as well as heads that she would attach to a body.8

| See Lily Darboy and all her accessories on Online Collections |

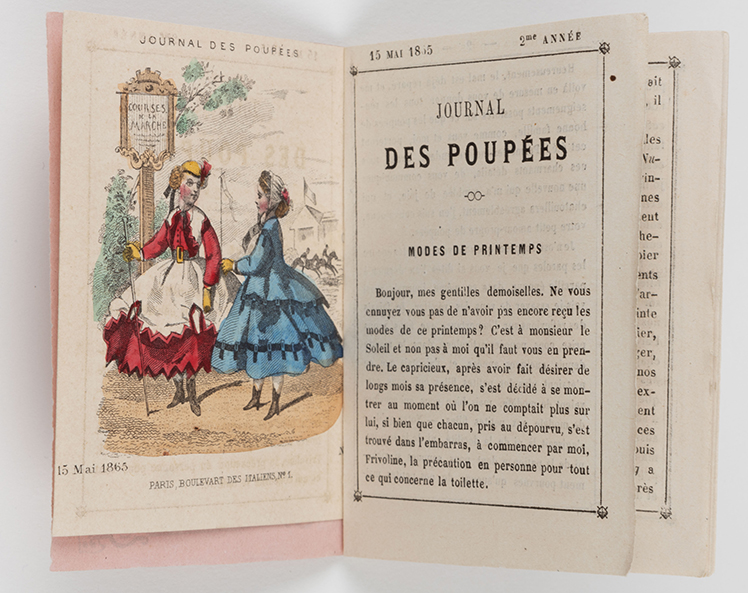

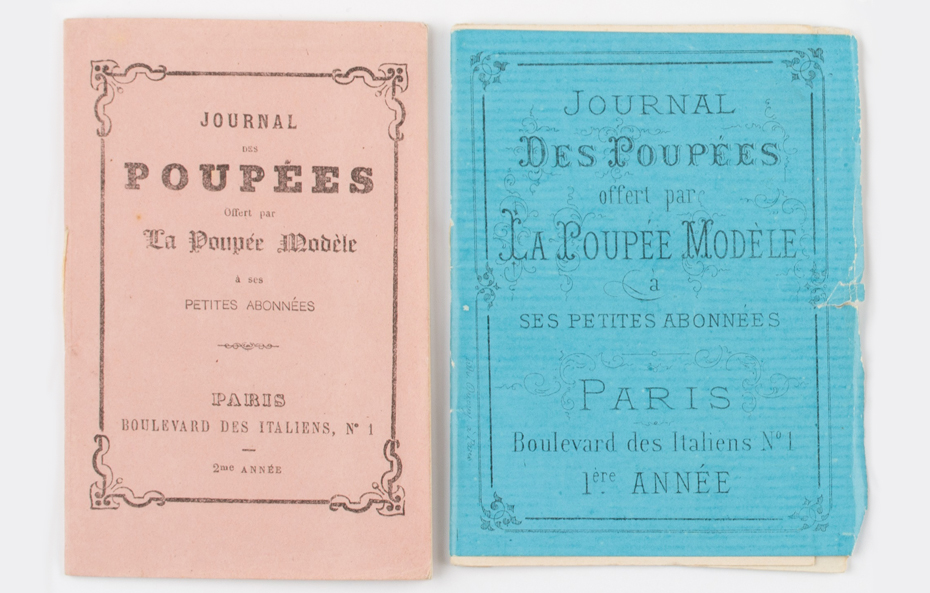

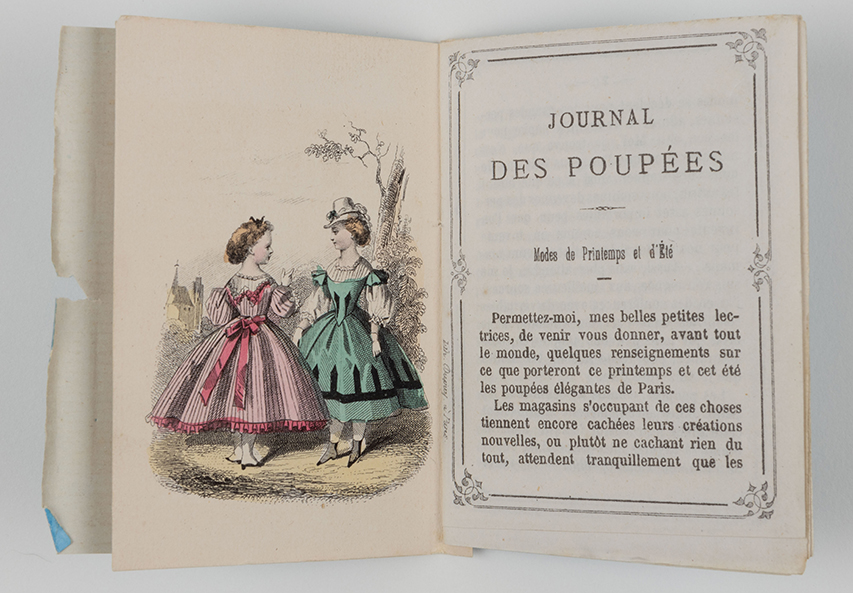

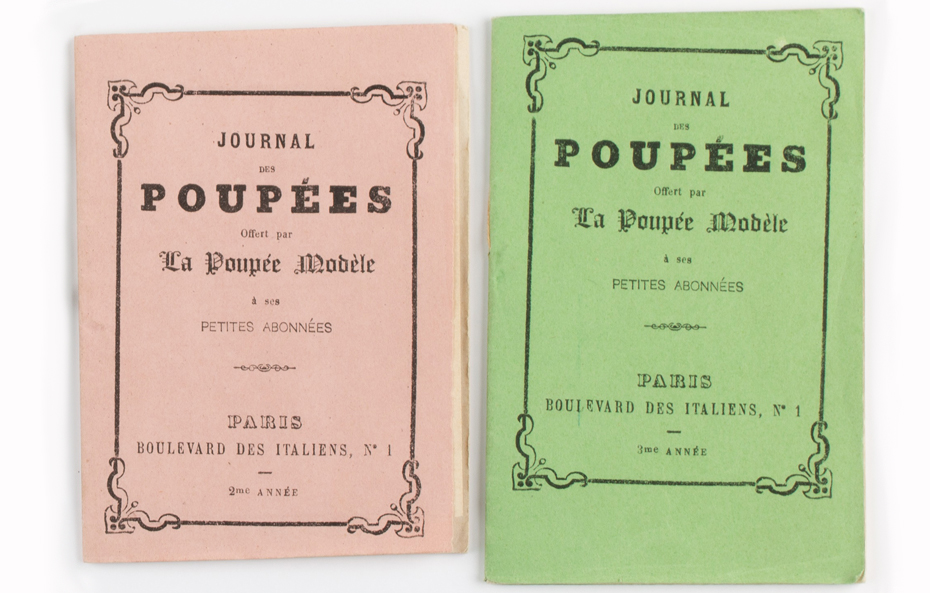

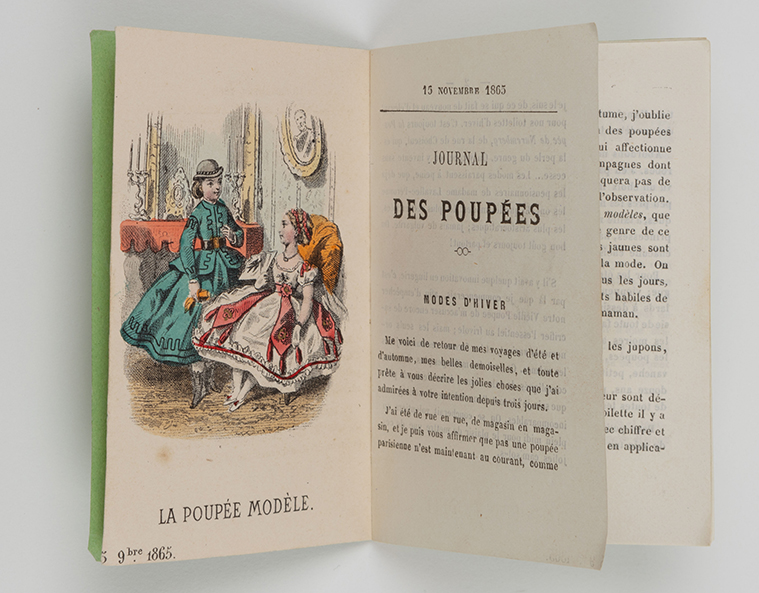

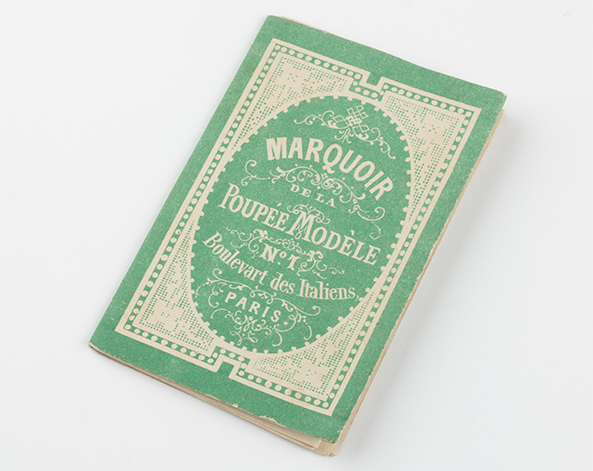

An enterprising woman, Madame Lavallée-Péronne promoted her Lily doll in the magazine La poupée modèle : journal des petites filles,9 a monthly publication that she produced and financed herself. Located at 1 Boulevard des Italiens in Paris, the editorial office had commercial ties with the many luxury doll stores concentrated in this neighbourhood.10

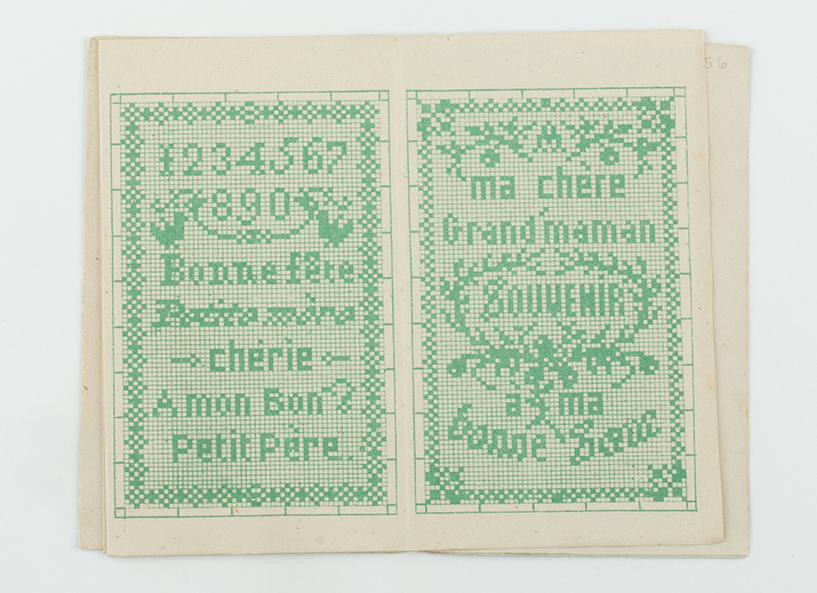

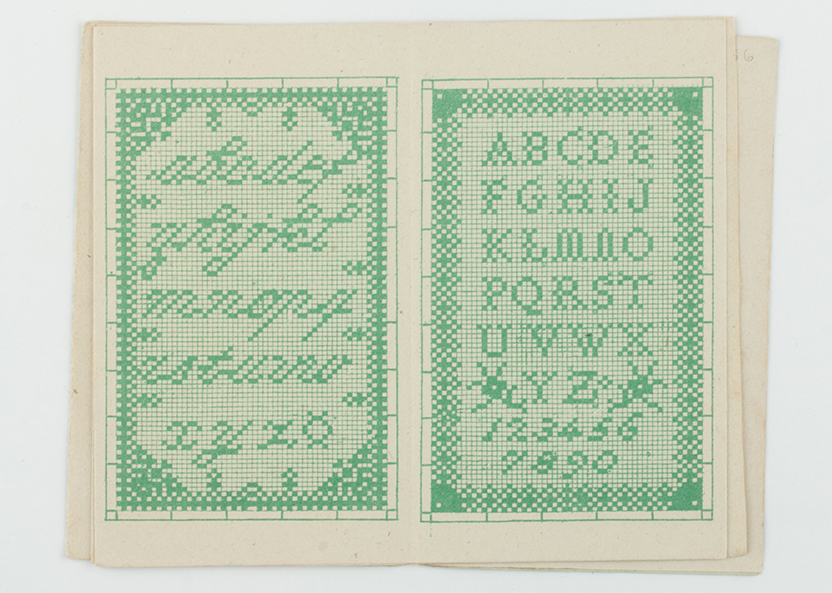

In the first issue of the magazine, an old doll, the voice of reason, told readers that the publication was designed to “teach you, while having fun, how to become good little girls: polite, pleasant and model little housewives.” The magazine thus offered subscribers projects like cardboard crafting, needlework, and sewing patterns, along with poems, plays, sheet music and recipes for snacks and light meals.

A bonus miniature booklet, the Journal des poupées, of which we have several copies, is signed “your foolish Frivoline” and has several pages describing fashion and the latest looks.

There were so many examples of doll literature during the 19th century that it was considered an educational literary genre for moulding young readers’ minds to the dictates of the time.11 A close reading of these works reveals prevailing standards of behaviour and moral values, including beauty and fashion, domestic life and its associated activities and rituals, family status, marriage and the family.12 Mothers would educate their daughters and give them a model doll to verify whether the girls had internalized what they had been taught.

Lily, fashion ambassador

A woman of her time, Lily personifies an idealized female beauty. Her pale complexion—her head, shoulders and arms are made of bisque porcelain13—is set off by her round, red cheeks. Framed by blonde hair, her face features big blue glass eyes, a delicate nose and a small heart-shaped mouth. Wearing a corset, as was the fashion, her stuffed body covered in kidskin has a tapered waist, prominent hips and a well-defined bust.

Representing the fashion and dress codes of her era, Lily has a wardrobe impressive not only for its size, but for its elegance: morning clothes, house dress, afternoon dress, city dress, evening gown, mourning dress, sporting dress, horseback riding outfit and bathing suit, in addition to an assortment of blouses, skirts and stylish hats, not to mention the undergarments: corsets, crinoline, nightgowns, panties and more.

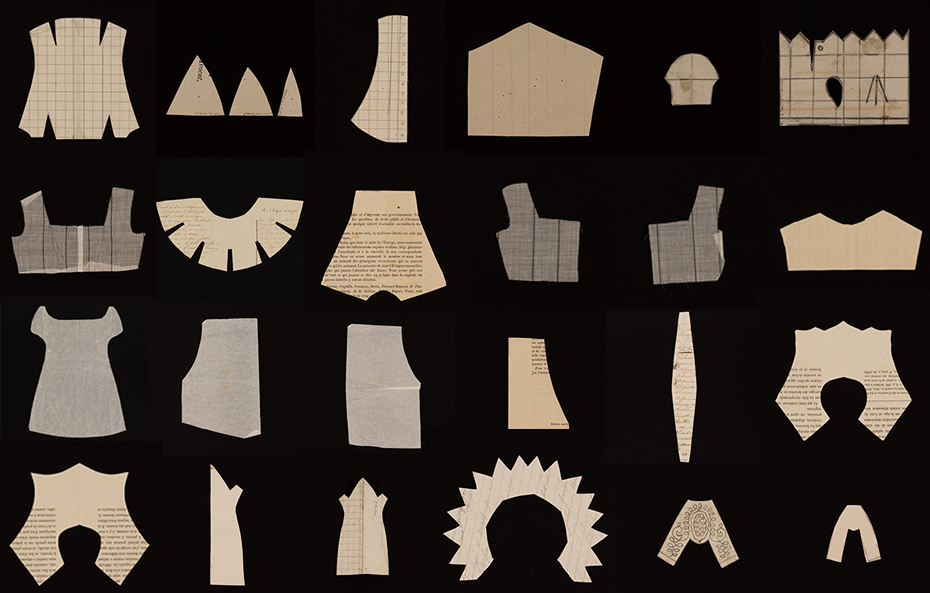

Lily has articulated shoulders and knees, making it easier to dress and undress her. Some outfits seem to have been made by Marie or another member of her family. They are inspired by patterns, of which we have several examples, published in magazines targeting young ladies like La poupée modèle.

Items that were not made at home were purchased from shops in Paris or elsewhere—dresses, stockings, boots and shoes, fans, handbags, gloves, umbrellas, furs, jewellery. Three sleeve boxes in Lily’s trousseau are stamped with Fourrures G. Beller, a furrier from Metz, illustrating that various manufacturers and suppliers were involved in the luxury doll trade.

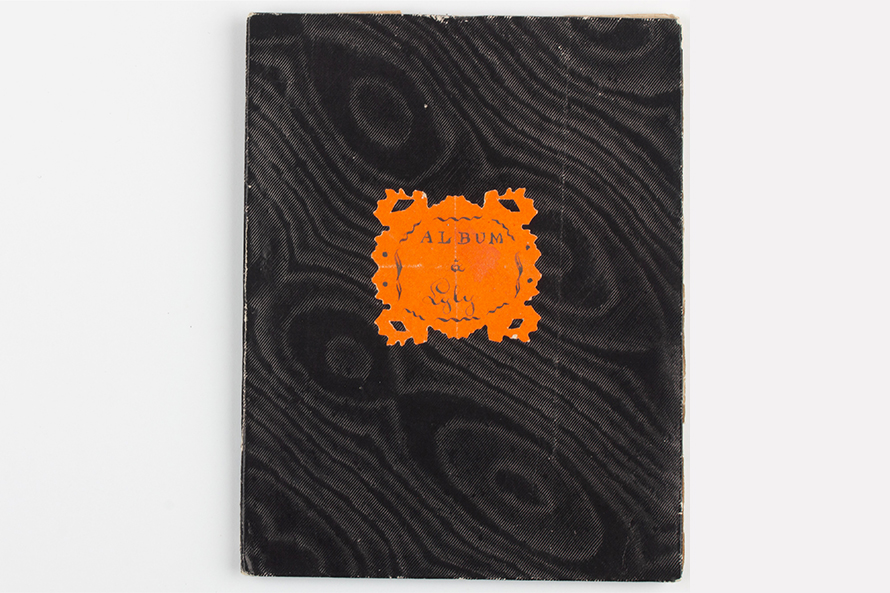

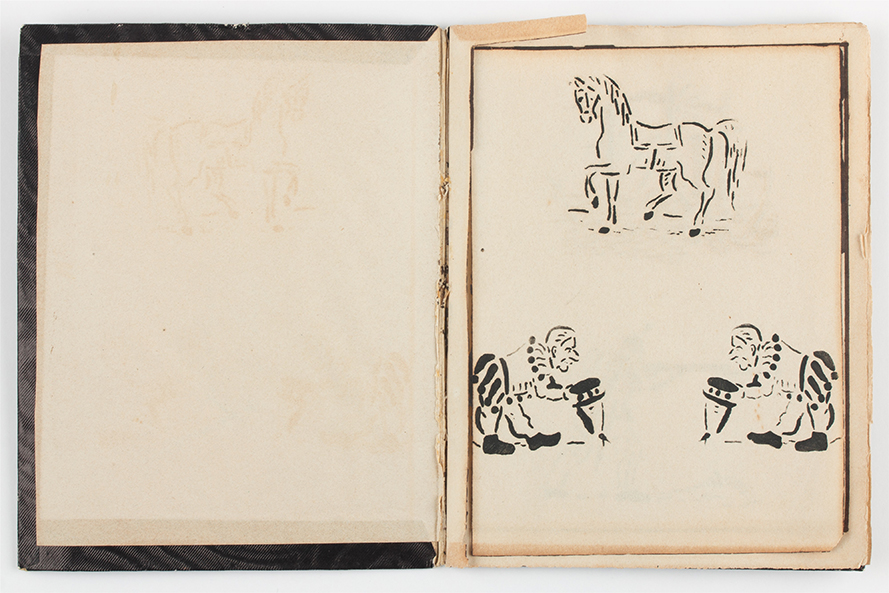

These beautiful clothes and accessories are accompanied by a multitude of small objects—comb, hairbrush, silver cutlery, ivory goblet, rosary and prayerbook, jump rope, piggy bank, whip, photo album—that were part of a bourgeois woman’s daily life.

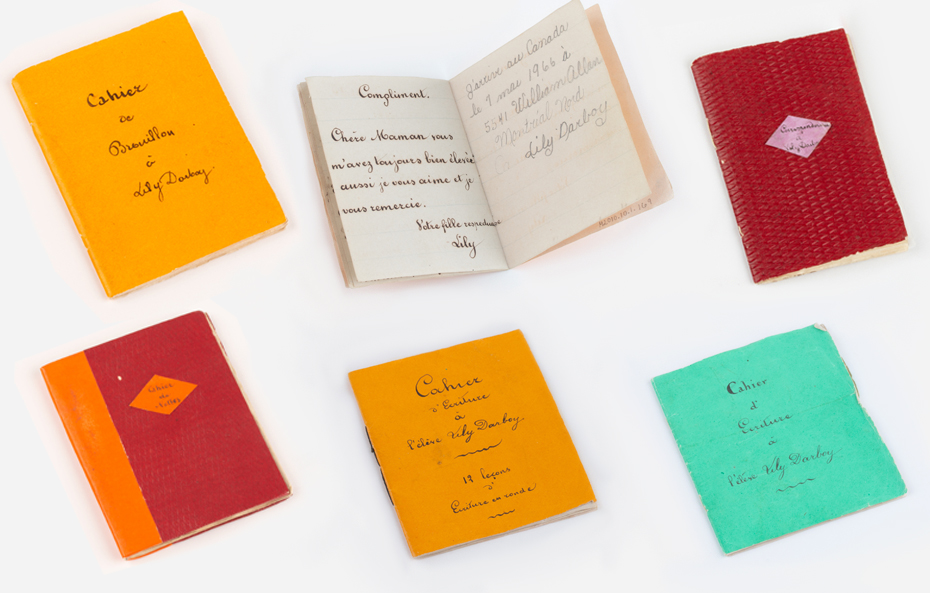

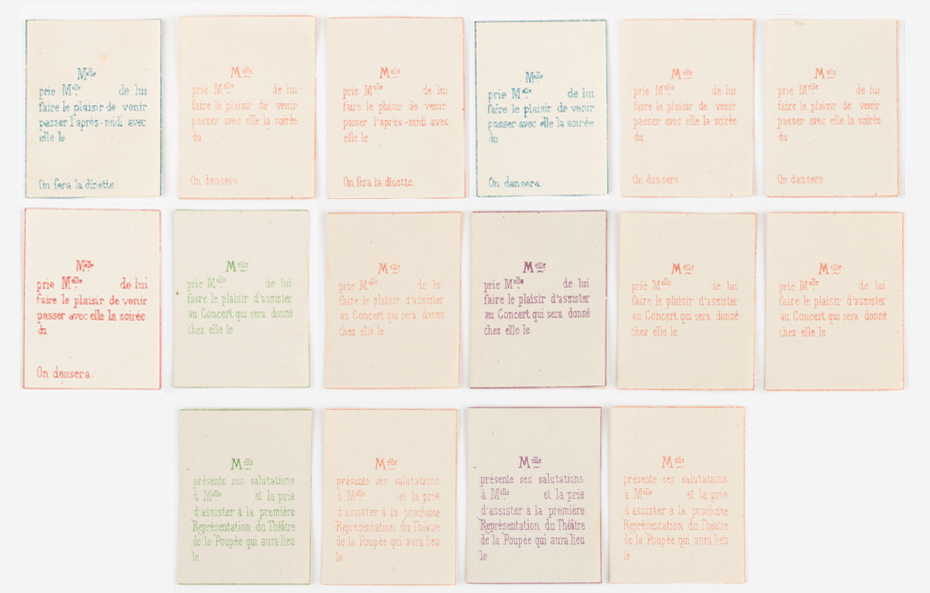

Used to replicate the social hierarchy of the adult world, Lily was an effective tool for helping girls assimilate the social and intellectual norms of the wife and lady of the house they would become. As such, educational objects featured prominently in the doll’s trousseau: writing and drawing notebooks, a sampler, and a sewing and embroidery basket reflect the desired manual skills and intellectual capacities. The ideal accomplished woman, Lily had to learn the customs and social codes of the bourgeoisie. She had to know how to welcome guests for tea, snacks and games, as well as socialize by engaging in activities like attending plays, concerts and receptions, and going on strolls.14

In 1875, Marie Eugénie Ida Darboy married Émile Sébastien Jules Ambroise (1850-1930), a solicitor in Lunéville. She had three children, including one daughter. Lily became a treasured family heirloom, handed down from one generation to the next, from one woman to another, for approximately 150 years. She arrived in Canada on May 7, 1966, a date recorded in one of her notebooks, and was donated to the McCord Stewart Museum in 2010. A precious material and symbolic witness of one family’s history, Lily now reassumes her role as a representative of female fashion and social history, a story that the Museum is proud to share.

Notes

- Victor Hugo, Les Misérables, [online].

- Marie-Françoise Boyer-Vidal, “L’éducation des filles et la littérature de poupée au XIXesiècle” in Genre & Éducation : Former, se former, être formée au féminin (Mont-Saint-Aignan: Presses universitaires de Rouen et du Havre, 2009) [online]. (February 5, 2024).

- Sarah Maza, “Toy stories : poupées, culture matérielle et imaginaire de classe dans la France du XIXe siècle,” Revue historique 2, no. 694 (2020) [online]. (February 5, 2024).

- Lucy H. Hooper, “Parisian Shop-Windows,” Appletons’ Journal of Literature, Science and Art XI, no. 262 (1874). According to the CPI (Consumer Price Index) calculator for the year 1863, this amount represents approximately US$500 today.

- The 19th century was the golden age of French dolls. In Toy stories, Sarah Maza notes there were 90 shops in 1848. In Les poupées françaises (Arthaud, 1986), Robert Capia mentions there were one hundred or so shops in the mid-19th

- Édouard Fournier, Histoire des jouets et des jeux d’enfants (Paris: E. Dentu, 1889), 65-66.

- Georges Darboy (1813-1871) was the Bishop of Nancy from 1859 to 1863, then Archbishop of Paris from 1863 to 1871. Taken hostage during the Paris Commune, he was executed at La Roquette prison on May 24, 1871.

- Sylvia MacNeil, The Paris Collection: French Doll Fashions and Accessories (Cumberland: Hobby House Press, 1992), 16.

- Designed for girls ages 6 to 12, La poupée modèle (1863-1924) was produced by the same publishers as the Journal des Demoiselles (1833-1896). Lily was one of the dolls featured in the magazine, along with Chiffonette, Bleuette and La Vieille Poupée.

- Dorothy S. Coleman, Elizabeth A. Coleman, Evelyn J Coleman, The Collector’s Book of Dolls’ Clothes: Costumes in Miniature, 1700-1929 (New York: Crown Publishers, 1975), 97, 104-106.

- Boyer-Vidal, “L’éducation des filles.”

- Laurence Chaffin, “Le roman de poupée ou le modelage des consciences,” La revue des livres pour enfants 222, [online]. (February 14, 2024).

- Bisque (also known as biscuit) is a hard-fired, unglazed porcelain.

- Lily’s “stationery” was appended to the 1865 edition of the magazine La poupée modèle. The various elements revealed the types of activities she engaged in. The month of November included writing paper, envelopes, invitations and paper for verses and New Year’s greetings, while the month of December had invitations to a ball, a performance, a light meal and a doll concert.La poupée modèle : journal des petites filles, Paris, 1865. (The Bibliothèque nationale de France has digitized every issue of this magazine, which can be consulted via Gallica, its digital library.) [online]