The pleasures of an organized closet

A closer look at the roles and dissatisfactions of the perfect homemaker.

September 8, 2020

This series of 12 articles written for the Shared Emotions project uncovers feelings, sensations and values buried in archival documents and looks at how they are shaped by the cultural and historical context of the time.

______

“What a joy attractive, well ordered closets can be—and it is such fun to decorate them!”

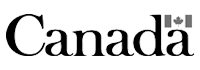

With this tantalizing promise of joy, the Singer Sewing Machine Company introduces the section devoted to closets in its 1940 Home Decoration Guide. Using illustrations, the booklet explains how to use attractive fabrics to decorate closet shelves with ruffles, cover hat boxes and hangers, and make garment bags and shoe bags.

Written for housewives, this very detailed guide teaches the art of decorating the home using fabric furnishings. It presents a variety of projects, from recovering armchairs to dressing windows, to making bedspreads and slip covers for the car. These types of ‘do-it-yourself’ projects are, in the words of the manufacturer, an achievement in which you “naturally take pride,” and the impressive results would no doubt generate excitement on social media today!

“You will enjoy making them immensely, but your joy and pride in seeing them finished and in use will even surpass that.”

Far from being a relic of a bygone era, the idea of finding joy in maintaining a harmonious, well-ordered home continues to resonate today. A veritable social phenomenon, the method promoted by Japanese organizing consultant Marie Kondo has made decluttering a way of life that promises joy and serenity. This trend is fuelled by the many images of minimalist décor circulating on the Web. Since the COVID-19 lockdown began in March, spring cleaning seemed to be an ideal activity for occupying body and mind. The media was quick to offer suggestions and advice on how best to do this, while reinforcing the mental benefits of such an activity1.

THE ROLE OF DOMESTIC GODDESS: SOURCE OF FULFILMENT OR DISSATISFACTION?

In the years following the Second World War, women were strongly encouraged to return to the domestic sphere. This was notably done by closing the nurseries and daycares that had been set up for them when they were needed to alleviate labour shortages during the conflict. Those who had entered the public sphere thanks to the women’s suffrage movement and had been part of the work force during the two world wars were now promised happiness and fulfilment if they reverted to the “natural” roles of wife, mother and housekeeper traditionally assigned to them.

In Quebec, this ideology was notably present in the words of Father Albert Tessier, who helped develop the province’s Family Institutes (post-secondary institutions for girls) as the Inspector Propagandist for regional home economics schools:

“Women instinctively detest clutter and uncleanliness. Tormented by dust, dirt and disorder, every day they engage in endless scrubbing, dusting, and cleaning. They are happy to complete these tedious tasks because they are rewarded by the joy of seeing everything shine in their home. Housewives hum as they wield brushes, brooms, feather dusters and dishcloths because they are in their element when they clean” 2.

The successors to home economics schools, which were first established in 1882, Family Institutes were created in the 1940s and 1950s. Although their instruction was primarily devoted to housekeeping, it also prepared young women to be in charge of household administration, child care and family health and well-being. Tessier called these accomplished women “unparalleled women,” that is, “unique women, without parallel, who diligently take care of everything in the home. Home economics must teach them how to be attentive, prepared, pious women who always think of others before themselves, who are always busy” 3.

Young women enrolled in home economics programs were also supposed to develop aesthetic skills and the ability to create a welcoming interior:

“It is also essential that the home be beautiful and decorated with taste, which is defined as imparting style without spending a lot of money. For women, linens are practical and indispensable, needed for grooming and cleaning. An attractive linen closet, full of carefully stored fresh, white linens, simple or decorated with lace and embroidery, is a sign of a serious home, and an organized, active housekeeper” 4.

With the advent of consumer society, this renewed appreciation for housewives became part and parcel of the idealized vision of suburban life that the growing middle class, with its improved post-war standards of living, aspired to. A single-family home, car and household appliances were the symbols par excellence of this new lifestyle embraced by nuclear families, who were moving out of cities to environments perceived as healthier and better suited to raising children.

However, this idealized conception of the housewife, who found fulfilment in maintaining a happy home and taking care of her family, was called into question in the early 1960s by Betty Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique. A product of middle-class America herself, Friedan identified a significant gap between the widely disseminated image of women, often seen in advertising and women’s magazines, and the dissatisfaction and despondency expressed by many women in her milieu. The book is critical of the pressure put on women of her era, many of whom felt alienated by having to conform to this ideal, despite the material comfort they enjoyed. While Friedan’s book is considered a key milestone in the evolution of North American feminism, it has been criticized by some for failing to address the situation of racialized and working class women.

OVERCOMING THE PRESSURE TO PERFORM

Last March when everyone was told to stay home because of the pandemic, the idea of doing a spring clean to create a sanitary, organized space to spend the lockdown made a lot of sense. Since then, however, a chorus of voices has risen to note that women already had their arms full, and that the lockdown exacerbated the unequal division of housework and increased their mental load5. No longer able to rely on the support of school, daycare or their circle of friends, some women even felt compelled to leave their jobs in order to focus on their family obligations. These observations and brief historical overview highlight the need to think critically about the pressure to perform that is evident on social media and often directed at women. But perhaps other concerns have convinced many of us that a Pinterest-worthy closet is no longer a priority!

TO LEARN MORE

- To learn more on the Fashion, Fabrics and Clothing Collection (C609)

- To learn more on the Shared Emotions project

- To learn more on the Textual Archives Collection

NOTES

1. Some examples: Caroline Michel, “Confiner, nettoyer, balayer : l’heure du grand ménage et du rangement,” Elle, March 27, 2020; Ryad Ouslimani, “Coronavirus et confinement : 4 raisons pour faire un nettoyage de printemps,” RTL, March 22, 2020.

2. Albert Tessier, Femmes de maison dépareillées, Fides, Montréal, 1945, p. 39, quoted in Maélie Richard, Les instituts familiaux de Trois-Rivières et de Cap-de-la-Madeleine : traditions et innovations, M.A. thesis (Quebec studies), Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, 2012, p. 67.

3. Maélie Richard, Les instituts familiaux de Trois-Rivières et de Cap-de-la-Madeleine : traditions et innovations, M.A. thesis (Quebec studies), Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, 2012, p. 49.

4. L’Économie Domestique à l’école normale, 1e, 2e, 3e, 4e années, Saint-Pascal de Kamouraska, Québec, 1938, p. 15, quoted in Jocelyne Mathieu, “L’éducation familiale et la valorisation du quotidien des femmes au XXe siècle,” Les Cahiers des Dix, 2003, no. 57, p. 144.

5. For example: Magdaline Boutros, “Le poids du huis clos sur les femmes,” Le Devoir, March 28, 2020; Catherine Handfield, “La charge mentale de la COVID-19,” La Presse, April 13, 2020; Emma, “Il suffira d’une crise,” July 20, 2020; Marie-Laure Josselin, “La COVID-19 fait reculer les femmes en science,” Désautels le dimanche.

REFERENCES

Anderson, Doris, “Status of Women,” in The Canadian Encyclopedia, April 2, 2014.

Baillargeon, Denyse, Brève histoire des femmes au Québec, Montreal: Boréal, 2012, 281 p.

Brisebois, Marilyne, “L’enseignement ménager au Québec : entre ‘mystique’ féminine et professionnalisation, 1930-1960,” Recherches féministes, 2017, vol. 30, no. 2, p. 17-37.

Chanda, Tirthankar, “La ‘ménagère désespérée’ de Betty Friedan,” RFI, February 21, 2013.

Chenier, Nancy Miller, “Canadian Women and War,” in The Canadian Encyclopedia, March 6, 2018.

Fox, Margalit, “Betty Friedan, Who Ignited a Movement With ‘The Feminine Mystique,’ Dies at 85,” The New York Times, February 6, 2006.

Friedan, Betty, The Feminine Mystique, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1963, 410 p.

Kondo, Marie, Spark Joy: An Illustrated Master Class on the Art of Organizing and Tidying Up, Ten Speed Press, 2016, 304 p.

Linteau, Paul-André, René Durocher, Jean-Claude Robert and François Ricard, Histoire du Québec contemporain. Le Québec depuis 1930, Montreal: Boréal, 1989, new revised edition, 834 p.

Mathieu, Jocelyne, “L’éducation familiale et la valorisation du quotidien des femmes au XXe siècle,” Les Cahiers des Dix, 2003, no. 57, p. 119-150.

Pierson, Ruth Roach, “They’re Still Women After All”: The Second World War and Canadian Womanhood, Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1986, 301 p.

Richard, Maélie, Les instituts familiaux de Trois-Rivières et de Cap-de-la-Madeleine : traditions et innovations, M.A. thesis (Quebec studies), Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, 2012, 109 p.

THANK YOU!

This project has been made possible in part by the financial support of Library and Archives Canada.