From Simple Beast to Devoted Companion: The Evolution of our Relationship with Animals

The relationship between people and animals has evolved a lot over the centuries.

May 28, 2021

This series of 12 articles written for the Shared Emotions project uncovers feelings, sensations and values buried in archival documents and looks at how they are shaped by the cultural and historical context of the time.

______

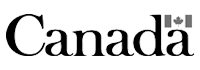

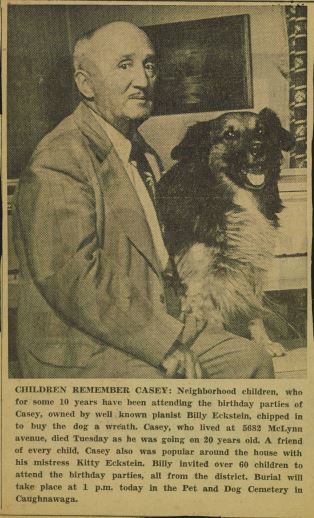

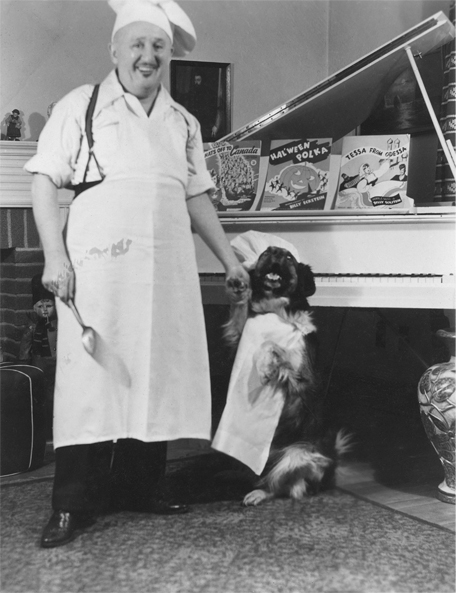

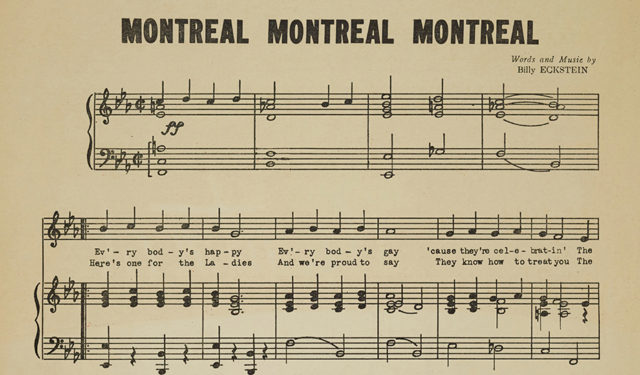

It is a spring afternoon in 1954. The setting is the countryside, several kilometres west of the village of Kahnawà:ke. Montreal pianist Willie Eckstein looks down at a little casket lying near a hole in the ground. His shoulders drooping, Eckstein gazes mournfully up at the sky. A little girl sitting nearby pulls up fistfuls of grass as a boy stares at the casket, holding back a sob. This unusual threesome has come to a pet cemetery to bury the legendary musician’s beloved dog, Casey. At least this is how I have imagined the sad event reported in this newspaper article from The Monitor, which was taken from one of Eckstein’s scrapbooks of photographs, press clippings and other memorabilia.

Eckstein loved his faithful companion so much that he wrote a song for him, a draft of which can also be found in the pianist’s archives. Casey’s birthday was celebrated with a party every year, to the delight of the neighbourhood children invited to attend.

PET BURIALS AND ACCESSORIES

Why did Casey have to be buried so far from home? As is still the case today, it is forbidden, for health reasons, to bury animals within the city limits of Montreal and many of its suburbs1. In 1950, Gratia Davidson, a Montreal resident who needed a place to bury her dog Honey, realized there was no such space in or around the city. Wanting to help other Montrealers facing the same situation, she decided to start a pet cemetery. Thomas Lahache of the Kanien’kehá:ka community came to her rescue, offering to lease her land on the reservation2.

Though pets are now ubiquitous in our society, when families first started keeping animals to amuse children and lighten hearts, the market responded by producing a variety of products and services specifically for them. By the late 19th century, pet food, particularly for cats, dogs and birds, became a common commodity3. A dog cemetery was founded in London around the same time, and by the early 20th century, British department stores devoted entire sections to pet supplies4.

A HIERARCHY OF ANIMALS: FROM LOYAL DOG TO SEWER RAT

When you meet a dog on the street, it is tempting to indulge in anthropomorphic interpretations of its body language. We enjoy attributing things about ourselves to the animal. That being said, human empathy regarding the sensitivity of animals has evolved a lot over time.

In the collective imagination of Western culture, there seem to be several categories of animals. There are pets, who handily win hearts, and farm animals, often kept out of sight. There are also those who resist us, like wild animals, whom we see as both terrifying and fascinating, and finally vermin, whom we find disgusting. This complex relationship with the animal world, which has persisted for years, has been influenced by scientific advances as well as popular culture and certain ideological movements5.

HIDE THIS CORPSE THAT I WOULD PREFER NOT TO SEE

The 19th century brought numerous cultural changes with respect to animal suffering. As Frenchman Jean Reynaud explains in an 1836 encyclopaedia article about the creation of slaughterhouses, “[…] people who live in cities are no longer condemned to the disgusting spectacle of the victims’ blood flowing in oozing streams, nor are they subjected to the putrid fumes emanating from animal waste […]. In addition, public mores may have become gentler, given that people are now completely unfamiliar with the pernicious examples of these cruel scenes”6. Clearly, empathy for animal suffering was not the primary driver of these changes; rather, they were motivated by sanitary reasons. The wailing of dying animals is disturbing and must be hidden away. During this same era, efforts were made to dissociate the idea of meat for consumption from that of the animal it came from7.

FROM ANIMAL SUFFERING TO THE ANIMAL NATURE OF HUMANS

At the same time, in the view of 19th century bourgeois society, animal suffering also had a moral dimension. A healthy mind was not supposed to express anger and passion, and those who abused animals demonstrated an animal nature that was both crude and immoral. In an interesting symbolic reversal, people who mistreated domestic animals were themselves called beasts8.

In fact, animal-welfare organizations were founded around this time, like the Canadian Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Montreal SPCA) in 1869. The prevailing philosophy behind education also underscored the benefits for children, notably boys, of taking care of a pet to develop the virtues of empathy and humanity9.

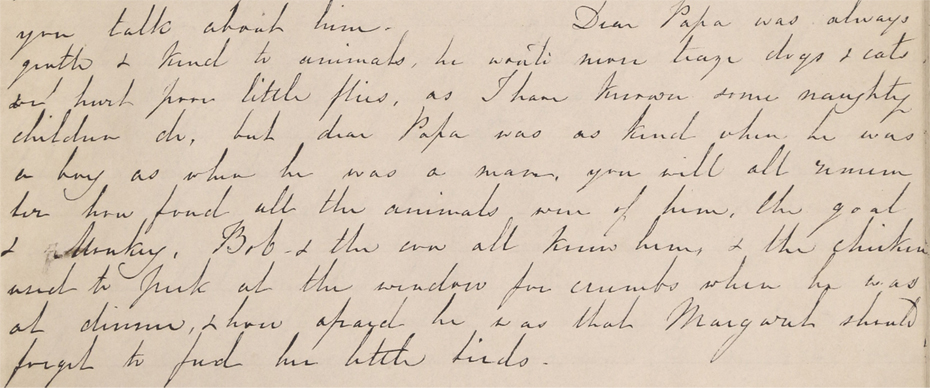

The same attitude can be observed in writings from that era. For example, in a tribute to her late husband, John Racey, a doctor who died battling the typhus epidemic of 1847, Susannah Withington Wise explains to her children how their father had always been kind and gentle to animals. “He would never teaze [sic] dogs and cats or hurt poor little flies, as I have known some naughty children do.”

BONDS OF AFFECTION AND DEPENDENCY

It can sometimes be disconcerting to make eye contact with a dog or cat. “What’s going on in your head?” I have been known to ask a cat with a piercing gaze. Pets have long been considered creatures of a sort, falling somewhere between object and subject.

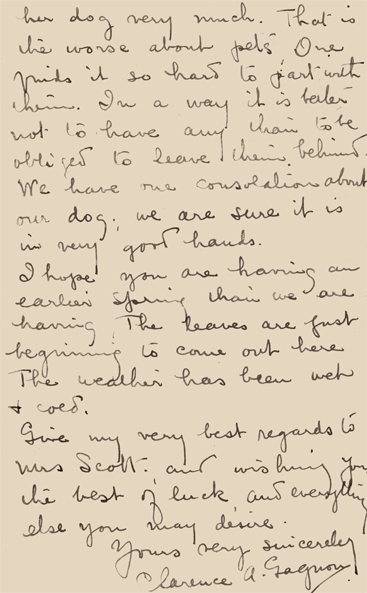

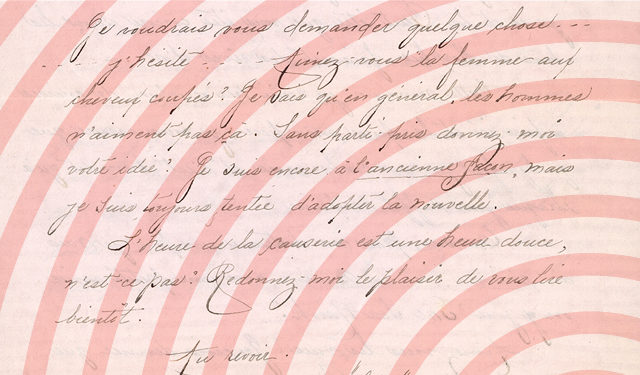

In his correspondence with writer Duncan Campbell Scott, painter Clarence A. Gagnon reveals an interesting mindset with regard to a puppy his wife had just acquired. A letter to Campbell Scott dated October 1923 recounts Gagnon’s first impressions of the new pet. One can just imagine him watching the puppy running around before he writes, “She looks as if she was going to be a good hunting dog.” He seems to be trying to objectify the animal, but two years later, when he and his wife are in London, he tells Campbell Scott that his wife misses the dog very much, and how difficult it is. “That is the worse about pets. One finds it so hard to part with them. In a way it is better not to have any than to be obliged to leave them behind.” With the passage of time, Gagnon became more emotionally involved with the dog, lessening the distance between the human world and the animal world. The sensibility that one recognizes in the eyes of another creature, animal or human, creates a bond between us. What a burden love is and how much simpler it would be to only think of oneself!

Today, our relationship with the animal world is a matter of great debate and in constant evolution. Once again, science, ideology, popular culture and economic forces come together in an effort to define what unites us with the rest of the living world. It is becoming increasingly clear that our fate is intertwined with that of the other creatures on this planet, in particular one unfortunate and now infamous pangolin.

Given the latest discoveries in biology and environmental science, in our relationships with animals, we must ensure that the idea of “us” includes “them”. As I look out the window, I catch the eye of a squirrel climbing up a utility pole. He stops suddenly, as if frozen in place, and stares at me with his bright eyes. In reply, I ask, “What do we do now?”

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Montreal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Fonds (P661)

Clarence A. Gagnon Fonds (P116)

NOTES

1. Similar measures regulating the disposal of deceased pets exist to this day in numerous Quebec municipalities. See Jean-Luc Lavallée, “Sera-t-il bientôt interdit d’enterrer son animal dans la cour des maisons de L’Ancienne-Lorette?”, Le Journal de Québec, June, 29, 2016, and the Montreal By-law concerning domestic animals.

2. John Ayer, “City Ruled No Burial Here, Pets ‘Rest’ in Indian Land,” The Gazette, May 24, 1954.

3. Amy L. Defibaugh, An Examination of the Death and Dying of Companion Animals, PhD thesis (Philosophy), Temple University, 2018, p. 60.

4. Ibid. and Sarah Amato, Curiosity Killed the Cat: Animals in Nineteenth-Century British Culture, PhD thesis (History), University of Toronto, 2008, p. 58.

5. Groupe de recherche en histoire des sociabilités, Humanités-Animalités. Discours, pratiques et actions sur le monde animal. (consulted April 14, 2021)

6. Pierre Leroux and Jean Reynaud (eds.), Encyclopédie nouvelle ou dictionnaire philosophique, scientifique, littéraire et industriel offrant le tableau des connaissances humaines au dix-neuvième siècle, Paris: Librairie de C. Gosselin, 1836, vol. I, p. 3, quoted in Damien Baldin, “De l’horreur du sang à l’insoutenable souffrance animale. Élaboration sociale des régimes de sensibilité à la mise à mort des animaux (19e-20e siècles)”, Vingtième Siècle. Revue d’histoire, vol. 123, no. 3, 2014, p. 56. (consulted April 21, 2021)

7. Baldin, article cited, p. 58.

8. Pierre Serna, Animalité, animalisation, bestialisation. Groupe de recherche en histoire des sociabilités, HumanitéS-AnimalitéS. Discours, pratiques et actions sur le monde animal. (consulted April 14, 2021).

9. “If animals were being cultivated through pet-keeping, so were human beings, in a symbiotic process. Children, in particular, were encouraged to keep pets in order to cultivate their softer emotions. Learning kindness to animals during the childhood years was believed to lead to moral righteousness in adulthood. These ideas were current in the late eighteenth century and gained strength as the nineteenth century progressed.” See Amato, op.cit., p. 56.

REFERENCES

Amato, Sarah. Curiosity Killed the Cat: Animals in Nineteenth-Century British Culture, PhD thesis (History), University of Toronto, 2008.

Baldin, Damien. “De l’horreur du sang à l’insoutenable souffrance animale. Élaboration sociale des régimes de sensibilité à la mise à mort des animaux (19e-20e siècles),” Vingtième Siècle. Revue d’histoire, vol. 123, no. 3, 2014.

Dean, Joanna, Darcy Ingram and Christabelle Sethna, eds., Animal Metropolis: Histories of Human-Animal Relations in Urban Canada, University of Calgary Press, 2017.

de Coppet, Catherine and Séverine Cassar, “Cacher le sang des bêtes : de la tuerie à l’abattoir” [radio documentary]. In La fabrique de l’histoire. France Culture.

Defibaugh, Amy L. An Examination of the Death and Dying of Companion Animals, PhD thesis (Philosophy), Temple University, 2018.

Ducarme, Frédéric, et al. “What are ‘charismatic species’ for conservation biologists?” BioSciences Master Reviews, 2013, p. 1-8.

Groupe de recherche en histoire des sociabilités, “HumanitéS-AnimalitéS. Discours, pratiques et actions sur le monde animal”.

Maris, Virginie, Philosophie de la biodiversité : Petite éthique pour une nature en péril, Paris, Buchet-Chastel, 2010.

THANK YOU!

This project has been made possible in part by the financial support of Library and Archives Canada.