Transcestors

Challenging the Gender Binary in Photography. Transcript of a talk given by Hélène Samson as part of the McCord Discoveries series.

July 28, 2022

My talk looks at examples of cross-dressing documented in 19th-century and early 20th-century photographs.

My use of the expression ‘cross-dressing’ refers to the practice of wearing clothing not commonly associated with one’s assigned gender at birth. In addition, I have adopted inclusive language whenever possible, although I do use the titles originally provided when discussing historical examples.

I first got interested in this subject in 2015 when a portrait of a cross-dresser—someone we would today describe as a trans woman—was discovered in the Notman Photographic Archives. I will discuss this in detail a little later.

I was encouraged to look for other examples of transgender expression when I read an article by trans artist Zackary Drucker, who produced the Amazon series Transparent and guest edited “Future Gender,” volume 229 of Aperture magazine in 2017. I first heard the neologism ‘transcestors’ from Drucker. It is used to describe the pioneers who paved the way for gender fluidity by affirming their identity—which did not conform to the binary gender hierarchy—through visual representation. The editorial team of the magazine highlights the urgent need for trans imagery that is marked by complexity and compassion to validate the history of gender fluidity (Editors’ note, Aperture 229, p. 23).

OBJECTIVE AND METHODOLOGY

With this objective in mind, I found six case studies, dating from 1889 to 1927, in the McCord Museum’s collection of photographs. Using the information and provenance recorded for these photographs, I did research to find out precisely who these people were, and what role these portraits played in their personal histories. Though I have not managed to answer all of these questions in detail and with certainty, I have developed hypotheses. I have tried to stick close to what the portraits show, and what the context means.

SUMMARY OF OBSERVATIONS

The few portraits found illustrate that cross-dressing is a complex—far from straightforward—behaviour. Not all cases are the same. Driven by a variety of motivations, depending on whether one has been designated male or female at birth, it is a behaviour exhibited in a range of contexts: daily life, a single-sex workplace, costume parties, the entertainment industry, private clubs, artistic creations and the milieus associated with it, like the bohemians of Paris and the avant-garde in Berlin.

I noted that this behaviour is not necessarily connected to homosexuality or gender identity, although these groups often overlap.

From a historical perspective, it appeared obvious to me that photography is very important to the visibility of the trans phenomenon. While some representations of cross-dressing in the 19th and early 20th centuries can be found in paintings, these examples do not have the probative value of photography. Moreover, it appears that the photographic process in question is a differential marker of public and private. During the period under study, two major types of photography developed in succession: studio portraiture and snapshot photography. Very few examples of cross-dressing can be found in studio portraiture, which is indicative of the fact that 19th-century society forbid this behaviour. On the other hand, snapshot photography, which gave amateurs the freedom to take photos and control their distribution, revealed the historical existence of gender fluidity in people’s private lives.

CROSS-DRESSING IN THE 19th CENTURY

What do we know about photographs of cross-dressing in the 19th century? Very little, in fact, because, according to authors, the 19th century was not a defining period for the visibility of LGBTQ+ culture.1 Literature is a better source of information about this era, as Louis Godbout, a lecturer and researcher for the Quebec Gay Archives, has shown. The turning point for the visual affirmation of LGBTQ+ culture did not occur until the early 20th century when the Institute of Sexology was founded in 1919 by Magnus Hirschfeld and Arthus Kronfeld in Berlin. This was followed by the collection of erotic art compiled by sexologist Dr. Alfred Kinsey in the late 1930s.

SÉBASTIEN LIFSHITZ COLLECTION

These studio portraits are from the collection of Sébastien Lifshitz. Composed of photographs found at places like flea markets, yard sales and on eBay, this special collection confirms the scarcity of 19th-century transgender portraits. It covers 100 years of photography, from 1880 to 1980. Though the portraits are fascinating and intriguing, they are anonymous and most are devoid of any context so their significance is diminished.

This collection was displayed in the exhibition entitled Mauvais genre, at the 2016 Rencontre d’Arles photography festival, and was the subject of the accompanying catalogue of the same name. I would like to point out that of the 200 or so photos in the book, only 11 date from the 19th century. Photos of trans people from this era are very rare because of the social and legal repression of cross-dressing in public.

FANNY AND STELLA

The celebrated case of Fanny and Stella in London during the 1860s and 1870s is an example of this repression.

Stella and Fanny, or Ernest Boulton (1847-1904) and Frederick Park (1846-1881), respectively, were two British cross dressers who pretended to be sisters. Stella, who was said to be very pretty, played female parts in variety shows, while Fanny was her loyal companion. The problem was that they tried to carry their theatrical cross-dressing into daily public life. The two were hounded by the London press, who dubbed them the “He/She Ladies.” Fanny and Stella were charged with impersonating women in public and committing sodomy, both of which were crimes punishable by prison with hard labour. At the end of a degrading, widely publicized trial, they were acquitted as the prosecution failed to prove that sodomy had ever occurred.

Using the court records of the trial, author Neil McKenna has reconstructed their story in a book.2 Though a secondary source, it provides a wealth of information about the underground homosexual scene in Victorian London and the perceived depravity that was associated with it.

THE NOTMAN PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVES

We are now going to take a look at the examples found at the McCord Museum in the photographic archives of the Notman Studio.

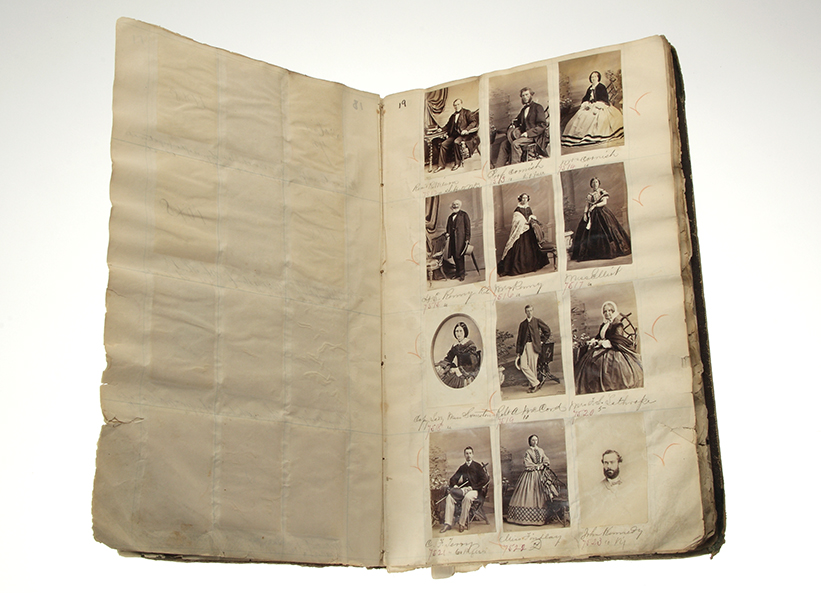

This is what the studio called a “Picture Book”—a large album containing chronologically numbered prints of all the portraits.

In the 19th century, studio portraiture was unusual in that it operated in both a contractual context and a public context. Before the Kodak revolution, the only way to have one’s picture taken was to go to a studio to use the services of a professional photographer. The relationship between photographer and client was contractual. According to the social code of the bourgeoisie, the photographer was paid to make the client look good. Studio portraiture played a normative role.

An additional feature of photography at that time was a context that could be described as public. The portraits purchased were actually exchanged among family and friends, often to be put into photo albums and frames. People used these portraits to present themselves to society. Furthermore, studio staff, and sometimes other clients, had access to the Picture Books. Under these circumstances, having one’s portrait taken became a public gesture, which doubtless explains why there are so few trans portraits.

SPECIAL EVENTS

Cross-dressing photos were nonetheless common in the context of special events, like masquerade balls, theatrical performances and variety shows.

Here are some examples of costumes worn for amateur plays. These types of photos are frequently found in the studio’s archives, recorded like any others in Notman’s Picture Books. The clientele was composed of members of amateur and professional theatre groups, along with convents for girls and colleges for boys who wanted photographs of their end-of-year plays, for example.

These examples of cross-dressing were socially acceptable because they were not deceptive. They did not threaten the well-defined, hierarchical categories between men and women. In essence, these portraits are unambiguous.

However, this was not true in the case of this portrait of Miss Georgie Bryton, taken by Notman in 1895.

Glancing at this photo today, one might wonder about this expression of masculinity. Is it a theatre costume or an example of transgender expression? The fact that the photo was included in the Picture Book indicates the context was likely acceptable. In fact, our research confirmed that the subject was a male impersonator from a variety show, the type that played music halls.

Georgie or Georgia Bryton (1881 or 1882-1942) was a British-born American actress who played in musicals on Broadway and elsewhere in the United States. She is known to have played at least one male role in a play in New York in 1902. According to an article in the Montreal Gazette, in March 1895, the Queen’s Theatre in Montreal hosted a British troupe for the show A Gaiety Girl! Although the article did not mention the artists who appeared on stage, the actress was photographed by Notman during her time in Montreal. Four photos were taken on March 8, 1895.

Notice the well-fitted formal men’s suit, which makes the cross-dressing believable.

Here is another portrait from the same session of Georgia Bryton dressed as an actress. Notice the stereotypical pose and wig.

We know that she was married and that she died in California in 1942.

This type of cross-dressing has been carefully studied using primary sources such as this. In some cases, the subjects are lesbian women or trans individuals, though many “male impersonators” were heterosexual cisgender women.

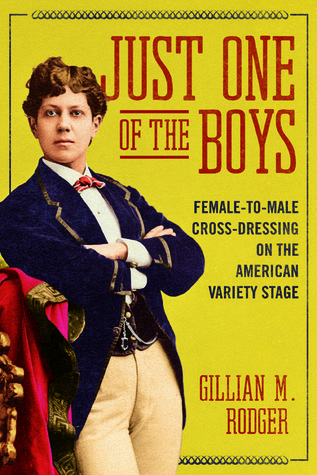

Here is a recent book on the subject by Gillian Rodger: Just One of the Boys. Female-to-Male Cross-Dressing on the American Variety Stage, published in 2018 by the University of Illinois Press. The cover portrait of actress Ella Wesner, taken by the Sarony Studio in New York City, is similar to those taken by Notman.

GENT FOR MRS. AUSTIN

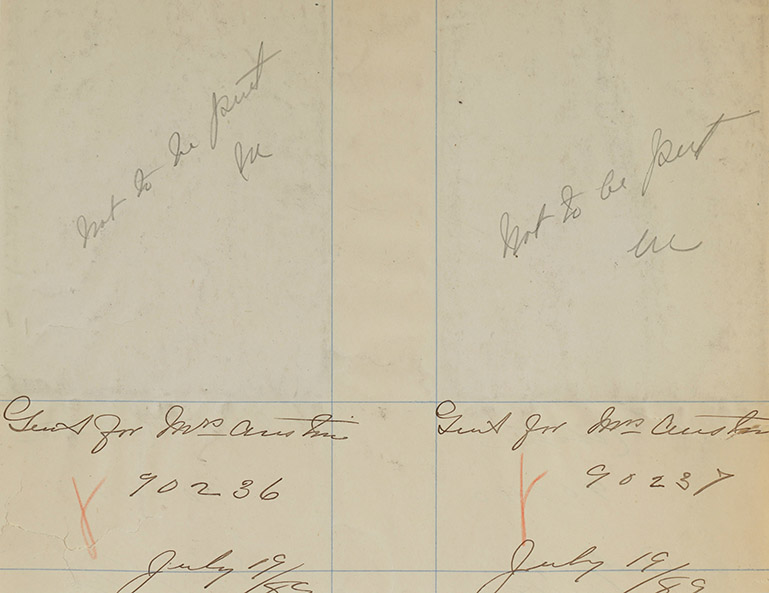

Now we come to an exceptional case, a true rarity, of a trans model whose portraits from the Notman Studio were to remain strictly private.

The young man in question, William Austin, had to be very determined and courageous to obtain a lasting visual image of his trans identity at a time of social repression. He risked being sent to prison or to a mental hospital. To get these portraits made, he was assisted by his mother and photographer Notman.

These portraits were never to be made public, as stipulated by the note inscribed in the Picture Book: “Not to be put in.” Notman had given the order not to include these portraits.

Let us take a close look at the negatives.

The head-and-shoulders portrait shows some standard retouching on the face. This portrait was created according to professional standards, indicating the sitter had the full co-operation of the photographer.

The traditional décor features a tea set, the dress is a little short, with a flat bodice, and there are some touch-ups to the ankles.

A detailed look at the unusual provocative pose reveals touch-ups around the bodice.

The title of these portraits is enigmatic: Gent for Mrs. Austin. Who is Mrs. Austin?

The discovery of these portraits where the “Gent” and “Mrs. Austin” are wearing the same hat led to the conclusion that she was Mrs. Windham Bruce Austin (1835-1918), the mother of the “Gent.”

This woman, Helen Winchester, born into a wealthy American family, was the mother of four children, all of whom were photographed at the Notman studio.

Through a process of elimination, I concluded that the “Gent” was William Winchester Austin (1865-1937), Mrs. Austin’s youngest son.

We can say that these portraits were part of the personal history of a young man whose gender identity was trans. First, he enlisted his mother to help him have his portrait taken at the Notman studio. Then, on July 10, her son’s birthday, Mrs. Austin herself had her picture taken at the studio and made arrangements with Notman for a sitting with her son. It is interesting to note that these facts point to an open-mindedness on the part of both mother and photographer. On July 19, the photographs were taken and it was noted that the prints were not to be put in the Picture Book, to preserve William W. Austin’s privacy.

Thanks to the 1911 and 1921 censuses, we also learned that William was institutionalized for at least 12 years at the Protestant Hospital for the Insane in Verdun, now the Douglas Mental Health University Institute. Access to his medical file is prohibited under the Privacy Act. However, he did not spend the rest of his life there, as he was living alone on Stanley Street in Montreal when he died in 1937. It would appear that these portraits were—in today’s terms—of a trans woman.

In 2016, I gave a detailed account of the research that enabled me to reconstruct this story at a Concordia University lecture as part of the Speaking of Photography series.

AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHERS

The following examples come from the private lives of amateur photographers. In the 1890s, amateur photography became popular and enabled those wielding the camera to control the distribution of the images, notably by developing their photographs themselves. In this way, portraits could remain private, which allowed the people in them to express their gender more freely.

ANNIE G. McDOUGALL

We are going to look at photos taken by Annie G. McDougall in the 1890s.

Annie McDougall was an amateur photographer in Drummondville. We see her here in the Notman studio, in an informal shot taken behind the scenes. She had accompanied her brother-in-law, Charles Millar, also an amateur photographer, who was purchasing a camera from Notman. I assume Annie posed for this photo so someone could demonstrate how the camera worked.

Never married, Annie McDougall was the librarian at the Fraser Institute in Montreal. She lived with her sister and brother-in-law, Charles Millar.

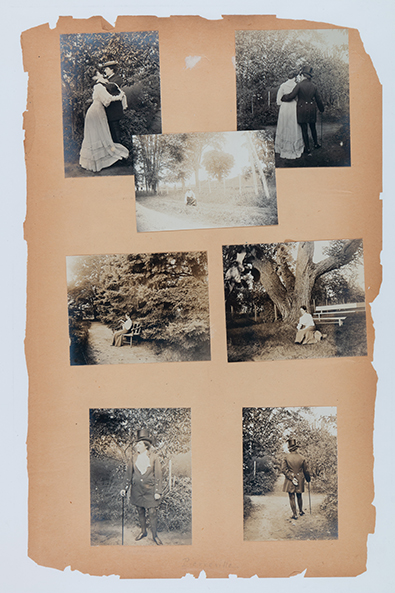

Among the photos by Annie preserved at the Museum is a large album containing this page depicting scenes of a heterosexual couple played by two women.

The photographs were taken in the 1890s. The models are Marie Gill, a friend of Annie McDougall, and Flora McDonald, a single woman who lived with her sister in Montreal. Marie was the sister of painter and poet Charles Gill, a member of the École littéraire de Montréal, a group that included poet Émile Nelligan. These people lived in a rich cultural environment, engaged with literature and the arts—a generally open-minded milieu. The photographs were staged in the garden of the Gill estate in Pierreville.

These scenes are reminiscent of “mock weddings,” a type of skit popular among young women of the era.

Notice the formal suit, not an everyday outfit.

How can this series be interpreted? Is it a playful illustration of make-believe? An artistic creation? Can it be seen as an acknowledgment of a lesbian relationship disguised as a heterosexual couple?

Annie McDougall’s album also includes these two photos of the same couple, this time in the garden of the Gill’s farm. Again, are we witnessing a scene from daily life or a fantasy? The question is still open.

MARGUERITE MARTHA "RITA" ALLAN

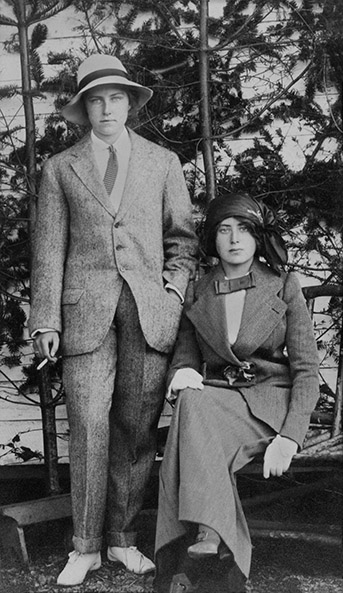

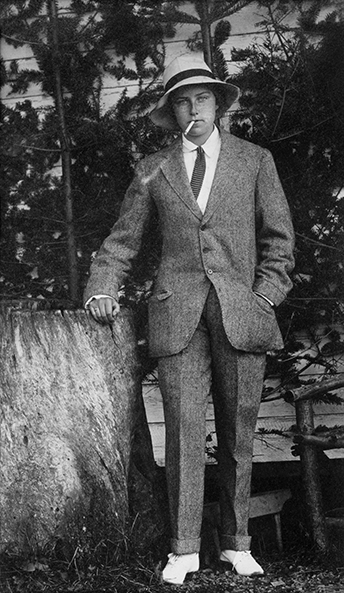

Taken in 1912, here is another example of cross-dressing, this time from the private life of Marguerite ‘Rita’ Martha Allan (1895-1942), a member of one of Canada’s richest families.

Rita and her sister Gwendolyn Allan were the granddaughters of Hugh Allan, the very wealthy shipping and Canadian Pacific Railway magnate who lived in Ravenscrag, a mansion on the slopes of Mount Royal in Montreal’s Golden Square Mile.

Seated on the right, Gwen met a tragic end. She and their other sister Anna drowned in the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915, three years after this photo was taken. Rita, who later went by the name Martha, is standing on the left, attired in a masculine outfit.

Here is another photo of her in the garden at the family’s vacation home in Cacouna.

It would appear that the suit was made for her: the pants and hat are typical of a casual male ensemble of the time. She is also smoking a cigarette, an omnipresent accessory for cross-dressing women at the time.

How can we interpret this instance of cross-dressing?

Martha Allan’s personality provides some clues to these youthful portraits. According to articles written about her, she was a person of character, very self-assured, determined, forceful and resourceful. Her family was active in the arts, theatre and music. Martha herself had a major influence on the Montreal theatre scene. Her career speaks for itself. She studied theatre in Paris, distinguished herself as an ambulance driver during the First World War, and worked in theatre in the United States before returning to Montreal in 1926. In 1930, she founded the Montreal Repertory Theatre, which operated until 1961. She also co-founded the Dominion Drama Festival.

We can see this case of cross-dressing as a manifestation of her desire for emancipation and the right to enjoy masculine privileges in world that was still very restrictive and narrow for women. Affecting a sort of dandyism, the young woman seems to be asserting herself by opting for a gender fluid style.

ROBERT ETHELBERT COOPER

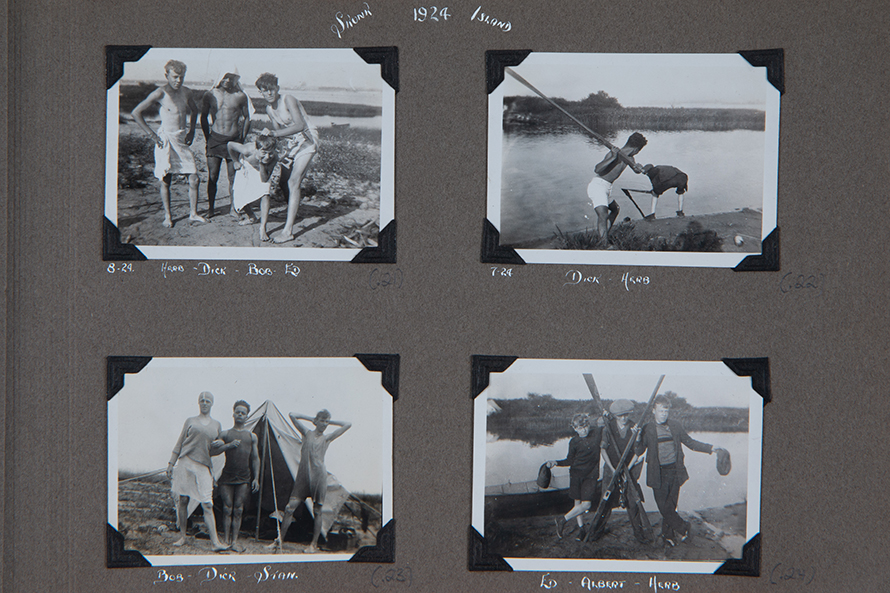

We are now going to look at two albums of snapshots from the 1920s, which include photos of cross-dressing.

Here is a page from an album created by Robert Ethelbert Cooper, dated 1927, where he can be seen dressed as a woman and as a man. The tone seems humorous.

The McCord collection includes a series of 10 family albums from Robert E. Cooper. The pictures depict only happy occasions—time with the family and neighbours, portraits, childhood memories, excursions around Montreal. The atmosphere of these albums is very joyful. Robert Cooper married and had one daughter.

We can see that his cross-dressing is rudimentary, not very meticulous, and that his posture remains masculine.

In these three photos, we see Robert dressed as girl but assuming a different name in each shot, taken in the backyard of the family home on Boyer Street in Montreal. His cross-dressing seems to be well accepted, as he gets his father and other family members to pose with him.

In this example, cross-dressing seems to be a playful theme for a very sociable individual with a keen sense of humour.

Studying the other albums in this fonds, I found these photos taken a few years earlier at a summer camp on Skunk Island in the St. Lawrence. These vacation snapshots feature a number of visual jokes.

In one photo, there is a simulated couple, and a young man imitating a woman with a suggestive pose.

What does this case of cross-dressing mean? Is it simply a game of transgressive, liberating, or even erotic dress-up, in a highly rigid masculine culture? Or is it perhaps an example of gender expression that, in a playful way, explores transgender identity? The discussion is open.

GEORGE JOHN ENGELHARDT

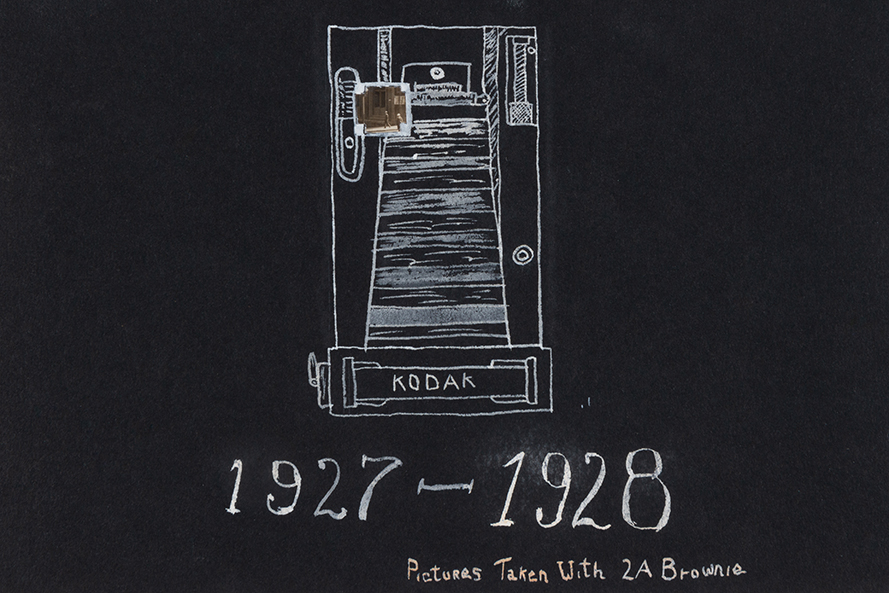

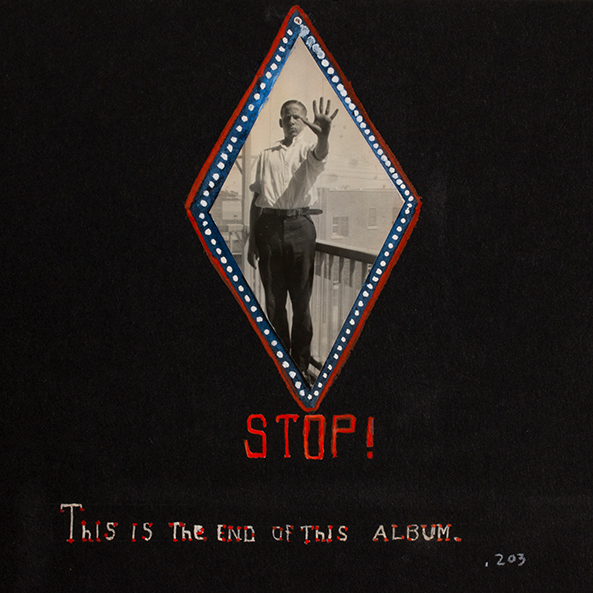

The last case is an album from presented as a book by an artist—budding photographer George John Engelhardt.

It is not a family album as the photographer/author is himself the subject. Furthermore, as the front cover makes clear, the book places photography centre stage. It is a book of “Pictures Taken With 2A Brownie,” an early handheld camera.

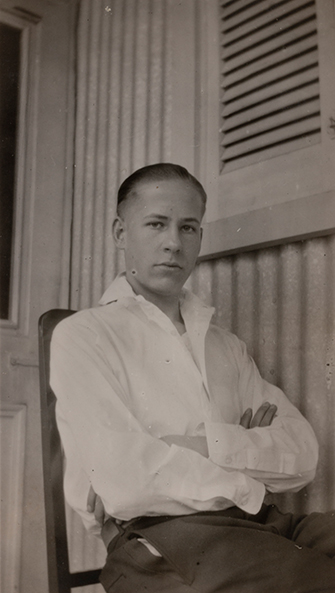

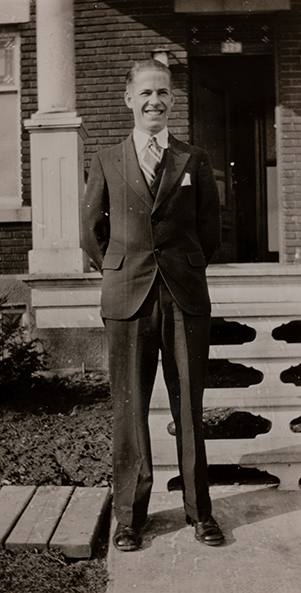

The album contains numerous self-portraits, including these two. Notice the well-groomed appearance and neat clothing. Who is George?

The Engelhardts lived in Teaneck, New Jersey, in the 1920s. In 1927, they moved to Beatty Street in Verdun. Father and son worked at the Belding-Corticelli Limited factory.

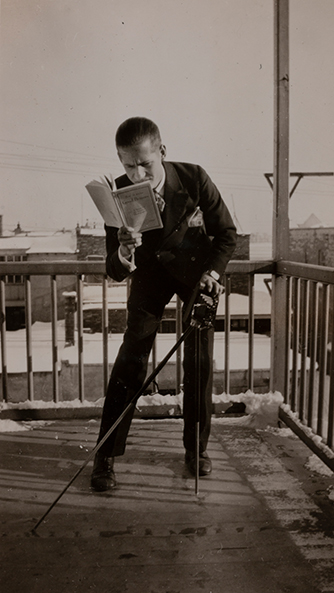

These images show that the album’s author is a self-taught photographer. He documents his artistic practice and darkroom, and includes drawings.

Here are the self-portraits where he is dressed like a female. The result is ordinary and believable: a simple dress, feminine pose, and elegant legs. In the second photo, he considers himself a vamp, a theme that we saw in two earlier cases: the Gent for Mrs. Austin portraits and the album of Robert E. Cooper.

These instances of cross-dressing are part of this young artist’s exploration of identity in which he questions, among other things, his gender identity. In this case, the cross-dressing seems to be a way to explore and express his artistic side.

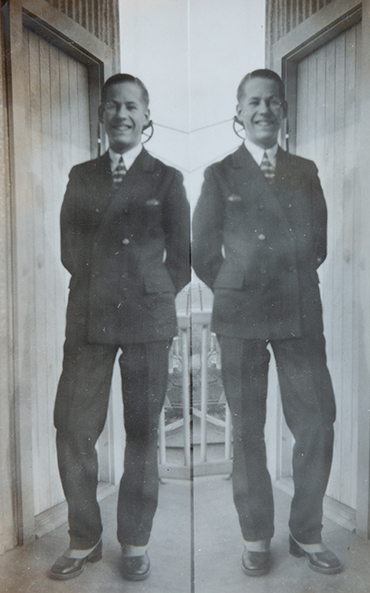

Another example of this exploration is this composite photo where George invents a twin brother, an alter ego.

He then closes his narrative portrait with a definitive final shot.

This concludes this series of photographic examples of cross-dressing.

Regardless of the motivations behind these portraits from the past, we must recognize that these photographs exist because they were truly wanted, at a time when transgender expressions were bold, transgressive, often risky, gestures. These portraits are, as Christine Bard explains in Mauvais Genre,3 the result of a firm intention. In these portraits, we can sense the pride and courage of assuming a trans identity, the satisfaction of performing, the creativity and freedom of playing with dress, the desire to be different, and a loving and erotic complicity.

As I said in my introduction, the photographic context shows that these expressions were reserved for the private sphere and that their visual representation is dissociated from homosexuality and a confirmed trans identity.

The performative and transgressive nature of these cases of cross-dressing dating back over 100 years makes them historical precedents for contemporary queer culture. Sharing them publicly today is also part of the political movement of queer culture.

NOTES

1. Lord, Catherine and Meyer, Richard (2013). Art & Queer Culture. Phaidon Press.

2. McKenna, Neil (2013). Fanny & Stella: The Young Men Who Shocked Victorian England. Faber & Faber.

3. Bard, Christine and Bonnet, Isabelle (2016). Mauvais genre – Les travestis à travers un siècle de photographie amateur. Éditions Textuel.