The Trials and Tribulations of Old Age

Thérèse Casgrain and seniors' rights: Timeless reflections.

July 7, 2023

This series of 12 articles written for the Shared Emotions project uncovers feelings, sensations and values buried in archival documents and looks at how they are shaped by the cultural and historical context of the time.

______

In the summer of 1976, Thérèse Casgrain, a leading activist who had fought to obtain voting rights for Quebec women, prepared to celebrate her 80th birthday. Though she had been in the public eye for many years, she was not happy to reveal her age. Interviewed five years earlier by television journalist Andréanne Lafond on Format 30, a show broadcast July 16, 1971, Thérèse Casgrain had said: I am very much a woman and the fact that everyone in Canada knows that I’m 75 years old bothers me a great deal.1

EIGHTY YEARS OLD

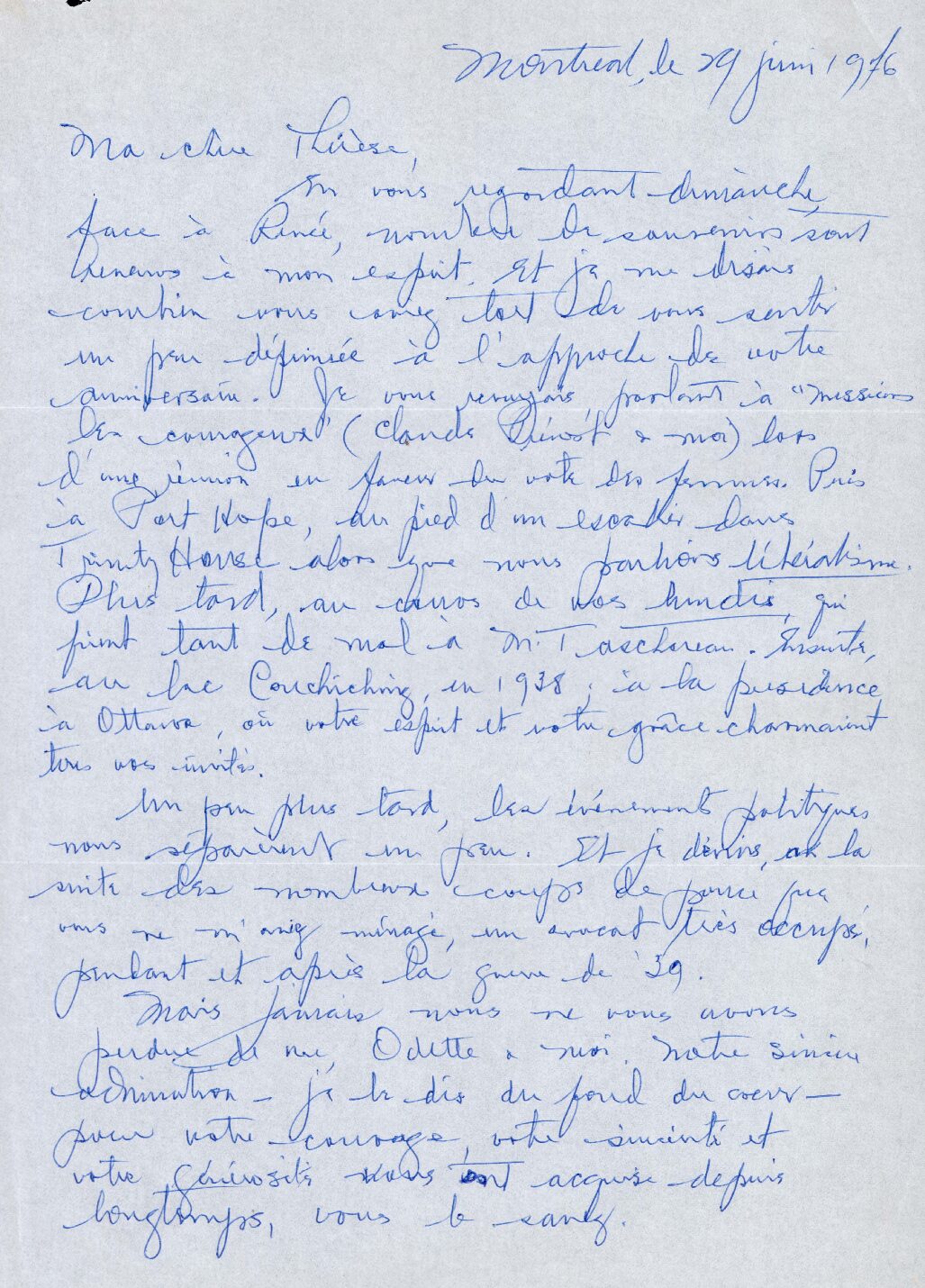

As her birthday approached, Thérèse Casgrain was so concerned that she discussed it with friends and family in her correspondence. The Casgrain, Forget and Berthelot Families Fonds (P683), which contains numerous letters, offers a look into this special time in the life of the legendary feminist activist and politician. In one letter, her friend Judge Roger Ouimet offers her support and comfort: “I was thinking how wrong you were to feel somewhat depressed by your upcoming birthday.” He goes on to reassure her by talking about her boundless energy, undiminished after all these years.

For Ouimet, this milestone made him realize that Thérèse Casgrain had made good use of her years to work for major causes. Expressing his admiration, he writes, “I really mean this—your courage, your sincerity and your generosity are greatly appreciated, and have been for many years, you know.”

Nonetheless, his friend’s concerns did resonate with him and he uses the opportunity to share his own fears:

Your eightieth birthday is simply another phase in your endless youth. I’m jealous of your youthfulness, as I will soon turn seventy and now find it difficult to hold a pen, as you can see. After a life spent fighting, I now find myself in a position of “almost” full repose, a situation that wears me down more than you can imagine. I repeat, I envy your daily energy that enables you to deal with a tired, breathless, overwhelmed 20th century.

June 29, 1976

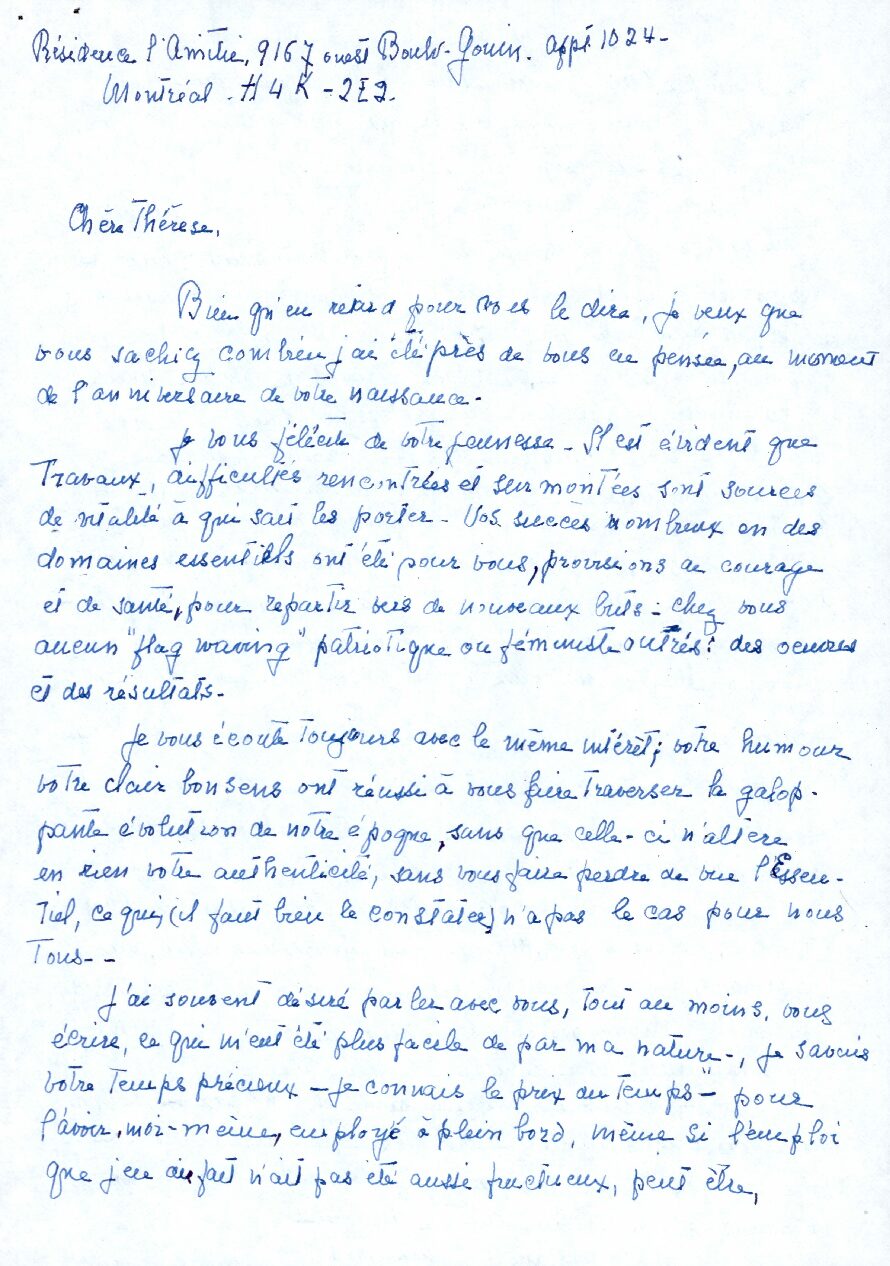

In her letter to her friend Thérèse Casgrain, poet Marie Saint-Jacques-Guimont also writes about the chaos of a constantly shifting era.

Your humour, your clear common sense have enabled you to get through the breakneck changes of our times, without it affecting your authenticity or making you lose sight of what is essential.

1976

Like Roger Ouimet, Marie Guimont takes note of Thérèse Casgrain’s vitality as she approaches her 80th birthday: “I congratulate you on your youth.” She then concludes, “Thérèse, I wish you health and happiness—I don’t need to tell you, keep going—you aren’t going to lose your momentum because it’s supported by your youthful spirit and heart.”

STAYING IN ONE'S HOME : THE FIRST CHOICE

For Marie Guimont, however, old age brought with it a decline in various aspects of her life:

I’m rapidly losing my sight, despite constant treatments, but apart from that my health is excellent and I don’t dare think about what awaits me. I can still enjoy the wide horizon, rivers and sky that surround my apartment in a semi-circle. I read as much as possible, armed with strong glasses and a large magnifying glass, and my handwriting is getting worse.

Marie Guimont explains that she had no choice but to leave her house, like many Quebeckers between 1960 and 1979, a period “characterized by a large-scale reliance on seniors’ residences and hospitalization, with no policy of keeping people in their homes,” as Stéphane Grenier writes in his study of the issue.2 The change in her living arrangements, made quite hastily, was a great shock to Guimont, who says in her letter that she feels “essentially destroyed.”

In fact, it was not until 1979, three years after this letter was written, that a policy “worthy of the name” was adopted and that the idea “of offering services closer to where people lived, in other words, in their homes, began to gain traction.”3

For Marie Guimont, residences like the one where she lived, although comfortable and managed humanely, were not acceptable long-term options. In her letter, she also mentions how the elderly are negatively affected by the lack of opportunities to interact with other generations:

It’s an artificial life without young neighbours, without children around, visiting your garden. A lot of people are very unhappy. It’s a stopgap measure, for almost everyone. I don’t think we should be building more of these residences. We have to find other solutions that will enable people to live out their lives in the homes where they have been living, among younger generations.

In other words, ageing in place, a living situation that many seniors have said they prefer, was already being discussed back in the 1970s, although it did not start being widely instituted until much later. As Grenier wrote in 2002: “We have just begun a period of institutionalizing the experience of home care and offering it throughout the province of Quebec.”4 More recently, on March 28, 2023, a report examining the state of home care support and services in Quebec was issued.5

Commissioned by the government, the report’s findings are extremely critical: over 20 years after the government launched its home support policy “Chez soi : le premier choix” (“Home: The First choice”), the resources available to meet the demand are still limited. Health and Welfare Commissioner Joanne Castonguay points at the failure of successive governments to implement this policy. And yet, it has been established for many years that, with proper support at home, “the elderly can benefit from their social network and usual home environment for longer. These benefits can be seen in both their physical health and social well-being.”6

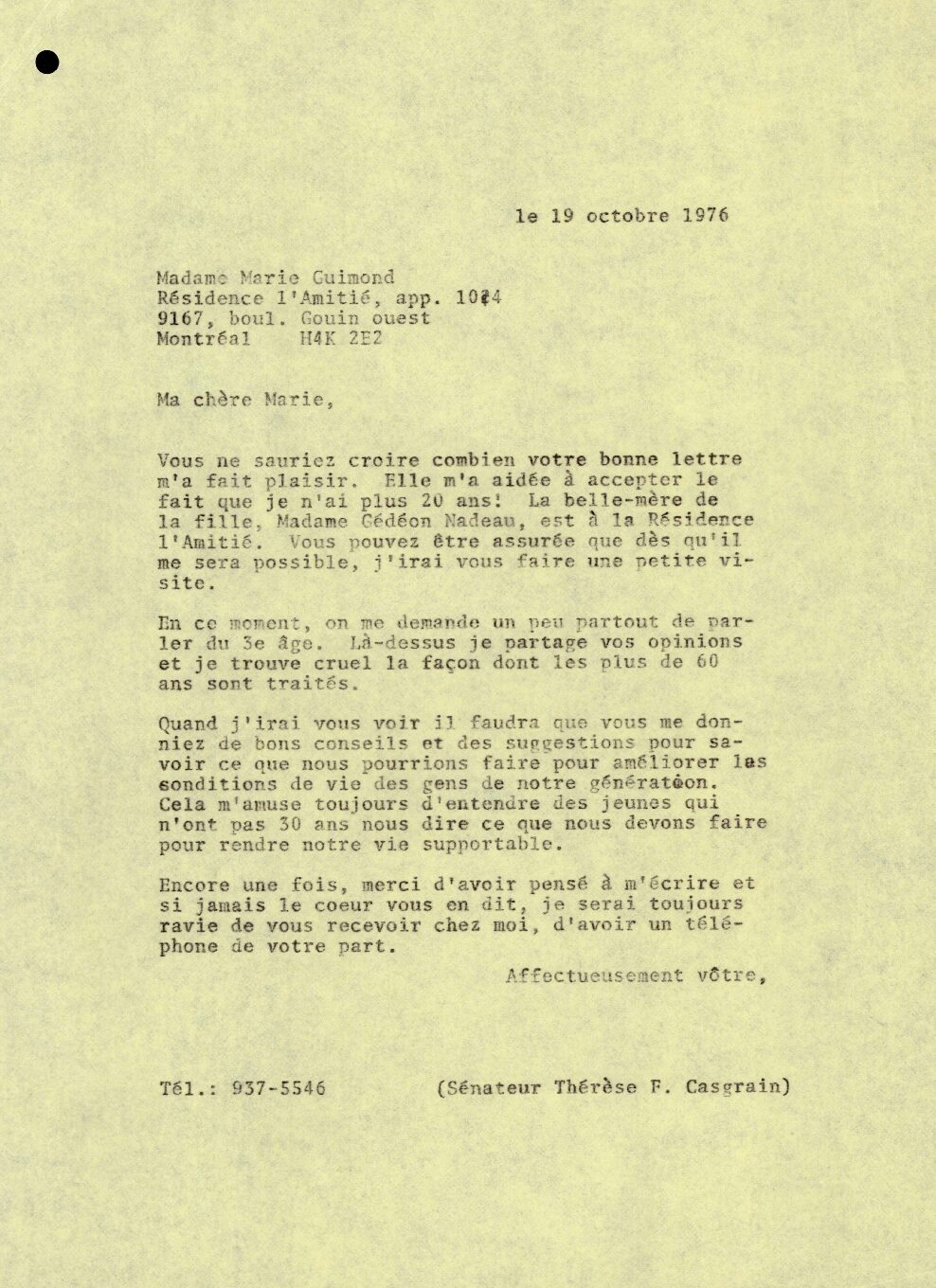

In her response to Marie Guimont, Thérèse Casgrain indicates that she is increasingly interested in the living conditions of seniors and asks her friend for advice, given that Guimont is grappling with the situation:

The next time I visit, I’ll need your advice and suggestions on how to improve the living conditions of people in our generation. I always find it amusing to hear young people under the age of 30 tell us what we should be doing to make our lives more bearable.

October 19, 1976

A TIRELESS ACTIVIST

From that point on, Casgrain, who received requests “from all over to talk about the elderly” (October 19, 1976), had an opportunity to look further into the subject. For this born activist, the struggle was part of her broader campaign to promote human rights, a cause she had championed for decades after helping Quebec women obtain the right to vote in 1940. As her granddaughter Lise Casgrain recalled, her grandmother “also fought for men, families, minors, the living conditions of prisoners, textile workers, the miners of Asbestos and the elderly. She wanted to change Quebec society and Canada as a whole and improve the living conditions of all citizens.“7

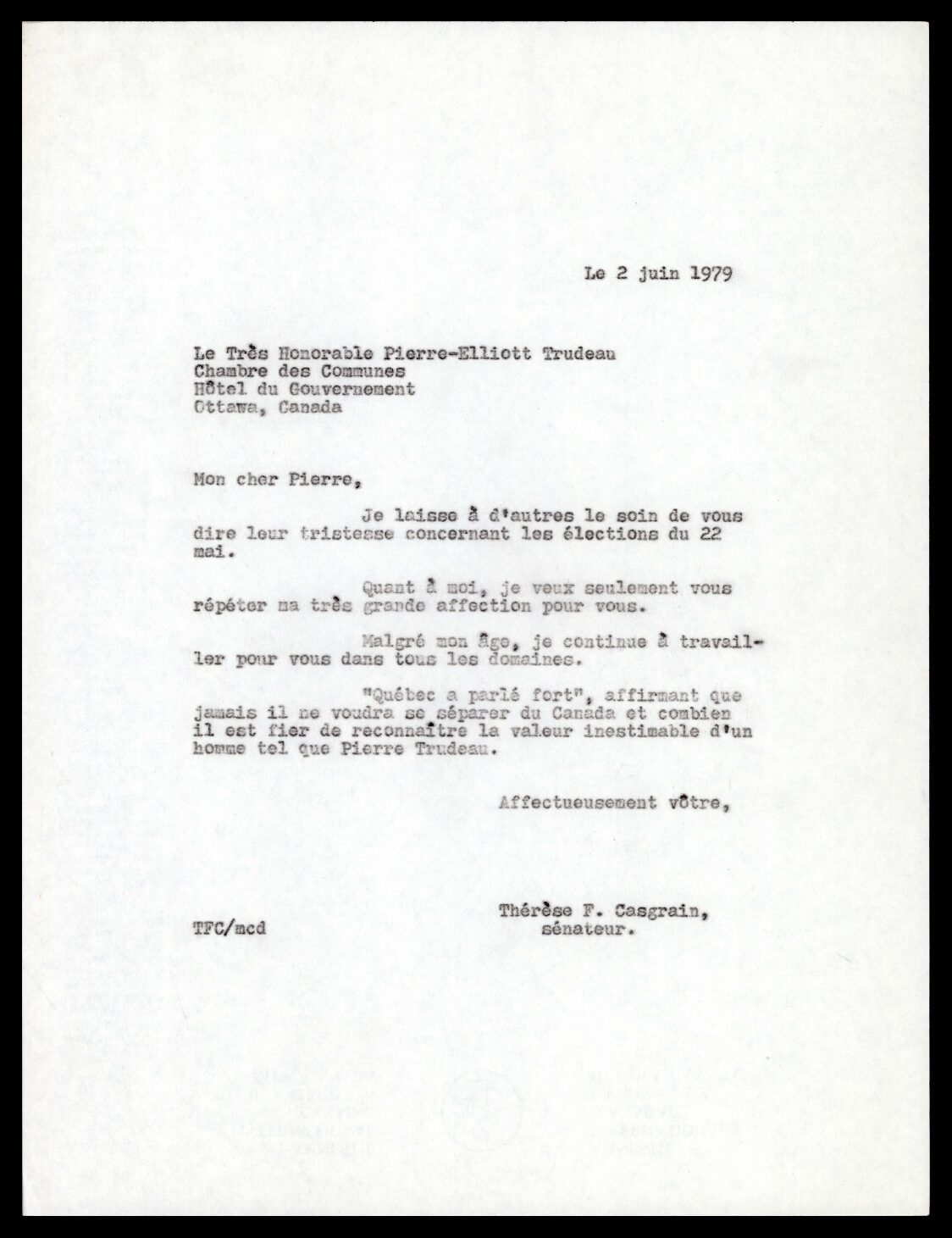

A tireless crusader, Thérèse Casgrain continued her commitment to public service by supporting certain politicians. Pierre Elliott Trudeau could count on her encouragement, even after he lost the 1979 election. In a letter to Trudeau, she shared her unwavering support:

Despite my age, I continue to work for you in every field.

June 2, 1979

No one can escape the march of time, so the theme of old age remains a universal concern that will become increasingly crucial as the population ages and questions concerning the rights and treatment of the elderly become more pressing. More than ever, as Commissioner Castonguay recently noted, the government must truly implement its home support policy to “better meet the changing needs of Quebeckers and their desire to age in place.“8 Shared nearly 50 years ago, the reflections of Marie Guimont, Roger Ouimet and Thérèse Casgrain remain very timely and focus on an issue that resonates particularly strongly at this moment, as we come out of the COVID-19 pandemic.

TO LEARN MORE

- To learn more on the Casgrain, Forget and Berthelot Families Fonds (P683)

- To learn more on the Shared Emotions project

- To learn more on the Textual Archives Collection

NOTES

1. “Archives – Thérèse Casgrain : donner une voix aux femmes du Québec,” Radio Canada, November 2, 2021 (accessed January 18, 2023)

2-4, 6, 8. Stéphane Grenier, Logement ou hébergement? L’évolution des milieux de vie substituts pour personnes âgées, cahier du Laboratoire de recherche sur les pratiques et les politiques sociales (LAREPPS), February 2002, p. 6-7, 9-10 (accessed January 18, 2023).

5. “Mandat du CSBE sur les soins et services de soutien à domicile – Bien vieillir chez soi : comprendre l’écosystème,” Newswire, March 28, 2023 (accessed March 29, 2023).

7. “Advancing Women’s Rights and Human Rights in Quebec,” Equitas, 2017 (accessed January 18, 2023). Thérèse Casgrain was one of the co-founders of the Canadian Human Rights Foundation in 1967, which was renamed Equitas in 2005.

REFERENCES

“Colloque Thérèse Casgrain – Cahier spécial,” Le Devoir, March 14, 1992, BAnQ numérique (accessed January 18, 2023).

Ducharme, Marie-Noëlle, Jean Proulx and Stéphane Grenier. “Étude des hybridations entre des formules de logement social et d’hébergement – Rapport d’étape portant sur les initiatives destinées aux personnes âgées en perte d’autonomie,” Cahier du Laboratoire de recherche sur les pratiques et les politiques sociales (LAREPPS), January 2013 (accessed January 18, 2023).

Ministère de la Culture et des Communications (Québec). “Casgrain, Thérèse,” Répertoire du patrimoine culturel du Québec, 2013 (accessed January 18, 2023).

THANK YOU!

This project has been made possible in part by the financial support of Library and Archives Canada.