The UMITEMIEU project: Holograms and movable collections

The creators of the UMITEMIEU project talk about this initiative that combines Indigenous traditions with virtual reality.

March 31, 2022

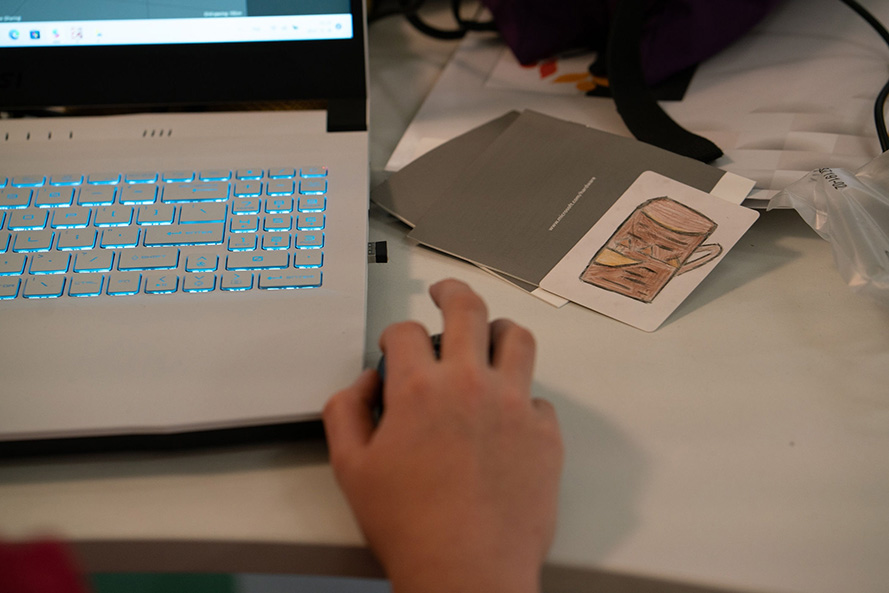

Seated around a conference table on the fifth floor of the McCord Museum are Emilio Wawatie, Stéphane Nepton and Leila Afriat, all of whom helped create the UMITEMIEU project.

Designed for the Indigenous peoples of Quebec, this project facilitates access to objects in the Indigenous collections of the McCord Museum and the Huron-Wendat Museum. A partnership with UHU Labos nomades and Concordia University, the program enables young people in Indigenous communities to interact with objects representing cultural identity as they develop innovative content using digital tools.

The driving force behind UMITEMIEU is the desire to increase digital literacy among Native youth and stimulate the intergenerational sharing of expertise and knowledge.

Would you please introduce yourselves?

Emilio: My name is Emilio Wawatie and I’m an Anishnabe from Barrier LakeI was raised in the Anishnabe culture, in La Vérendrye Park. My experience in the forest with elders was thus fundamental to my understanding of Indigenous cultures.

I began working on the UMITEMIEU project after being chosen for an internship created by Concordia University. I immediately loved the idea of collaborating with the McCord Museum and having a chance to study the objects in its collections. I was also inspired by the opportunity to revitalize our culture using digital technology. My role in the project has been to research objects found in the Museum’s education collection and document the workshops presented in the participating communities. I’ve learned a lot!

Stéphane: I worked in the video game industry for 23 years as a special effects artist. I now work full-time with my partner Andrea Gonzalez on UHU Labos nomades, our digital arts for Native youth initiative. Intergenerational transmission, community strength and cooperation are the objectives of our youth workshops designed to support school retention and cultural health. UHU Labos nomades collaborates on a variety of projects, but UMITEMIEU is really our favourite.

For the UMITEMIEU project, I did research and development, facilitated the workshops, and helped design the various visual media.

Leila: I’m a Project Manager, Education, Community Engagement and Cultural Programs at the McCord Museum. For the UMITEMIEU project, I have acted as a liaison between our various partners, schools and community members. In the field, I helped Stéphane lead the workshops. We’ve all pitched in at almost every stage of the initiative. I think the project’s strength is the spirit of co-operation that has motivated us from the beginning to the end.

What does the UMITEMIEU project mean to each of you?

Stéphane: The idea was really to have young people from participating First Nations communities create their own museum—a sort of virtual cultural collection. They were invited to take part in a photogrammetry session to capture a physical object. With the help of artificial intelligence, this process creates a virtual copy of the object. The object is then imported into an augmented reality program to produce a cultural hologram. The result is a movable virtual museum made by members of the community, for members of the community, which includes both youth and elders.

Leila: And these collections remain in the communities, where the members themselves decide what to do with them.

Dozens of partners like the Huron-Wendat Museum, the Tshakapesh Institute and the Kativik Regional Government have joined us in communities across Quebec. The project has evolved a lot since we began and I think that its portability, the fact that it can be adapted to the needs of communities, is one of its greatest assets.

From UHU Labos nomades, how did you end up working with an institution like the McCord Museum, which has a colonial past?

Stéphane: Geneviève Sioui, who is Concordia University’s Indigenous Community Engagement Coordinator, was the one to suggest that we collaborate with the McCord Museum. The symbiosis between our intentions and our values was immediately apparent—we instantly knew that this would be a special project. Working with the McCord Museum was a natural fit because all of our values are respected; listening, respect and goodwill are at the heart of the UMITEMIEU project.

It is imperative that members of Indigenous communities participate in decolonizing digital spaces. Decolonizing means asserting ourselves, creating, sharing, appreciating and protecting our digital heritage and culture. It’s important that this new digital literacy be taught, experienced and mastered for the future of our young people and our communities. Strength and renewal lie in protecting and creating our own data.

Leila: When I arrived at the McCord Museum, I wanted to do a project where objects in the Indigenous Cultures collection could be taken out and brought to communities using digital technology. When we heard about UHU Labos nomades and made contact with Stéphane, we realized that working together was the ideal solution. The initiative aligns perfectly with the Museum’s desire to build stronger connections with communities and decolonize its practices.

Could you talk more about the role of communities in the project?

Leila: Communities play a key role because they actually do everything—we’re simply facilitators. After looking through the Museum’s collections, community members select the objects from their nation that they would like to see scanned. The goal is to create a collection that is a cross between objects from the community and objects from the Museum’s Indigenous and education collections.

The communities also decide how young people will be involved and how this virtual collection will be presented. In Wendake, for example, they asked two conveyors of culture, band council chiefs and community elders, to make the selection. The school is transforming its library into a museum of Wendat history so the digital objects created by young people during the UMITEMIEU workshops will be integrated into their classroom museum project.

Stéphane: Everyone involved takes part in an act of shared cultural pride: the cultural pride of the community, on one hand, and the individual pride felt by students who, over the course of several workshops, play a very tangible role in building this collection while also acquiring new digital literacy skills.

Tell me about the relationship between indigenous traditions and the digital space.

Emilio: When we digitize an object, even if the physical object is eventually lost, the virtual copy enables us to preserve its form and how it’s made. Using digital files, we could create a new physical copy of the object. Thus, both the object and its memory are saved.

For example, the Huron-Wendat have many songs that have been brought back to life thanks to recordings made in the early 19th century. Today we are seeing traditions being revived thanks to these songs, which were recorded on wax cylinders. With UMITEMIEU, we are doing the same thing with digital tools instead of wax cylinders!

Stéphane: The workshop provides a pretext for intergenerational transmission. The digital space is a very attractive medium for young people to appreciate or reclaim their culture, but in an original and innovative way.

To give you a concrete example, Emilio and I differ in that he learned how to make birchbark canoes in his community before he learned how to make digital versions, while I, on the other hand, learned to make a digital canoe before learning how to make one out of birchbark! Needless to say, we have both shared our respective skills with the team, encouraging this transfer of personal experience along with digital, ancestral and Indigenous knowledge.

It’s important to preserve digital information while also protecting our ancestral knowledge. Since our elders will not live forever, we must rely on our young people to step up and preserve our culture and collective memories. Why not develop and improve the digital skills of each nation, while respecting each community?

What are your plans for the project and youself?

Leila: We’ve established enduring connections with our partners. We’re building long-term relationships and making the Museum’s resources available. We hope to bring the project to all 11 First Nations in Quebec.

Emilio: When I joined the project, I was galvanized and inspired to meet with members of other communities. That was my prime motivation. Though I’m interested in the idea of continuing to work in museums, I’m most excited about making things myself! For me, discovering all these things about Indigenous cultures is personal, cultural and educational.

Stéphane: Personally, I would like to reclaim my culture while sharing my knowledge with Native youth. At the same time, with UHU Labos nomades, we want to transmit our knowledge through digital arts workshops in all 11 First Nations in Quebec. In addition, why not hold workshops in Indigenous communities outside the country? Many of their cultural, environmental, social and linguistic issues are similar to those found in Quebec communities.

Geneviève Sioui, Concordia University’s Indigenous Community Engagement Coordinator, another project co-creator, was not present for the interview. Her role in UMITEMIEU is to advise the team on the partnership aspect of the initiative. She also supervised Emilio’s hiring and internship. Finally, she provided logistical support for the workshops held in the communities.

To learn more, read Concordia’s Office of Community Engagement contributes to a joint initiative in Indigenous schools available on Concordia University’s website.

The UMITEMIEU project is made possible thanks to the financial support of the Gouvernement du Québec.