McGill College: Where change is nothing new

History at your fingertips! The Urban Tours provide a fun way to learn more about the history of certain Montreal sites.

June 18, 2024

Take an exclusive outdoor tour thanks to historical images from the Museum’s collections.

Using your phone, explore the various tours and discover the history of many city sites and images that bear witness to the Montreal of the past.

The McCord Stewart Museum invites you to take a short walk that offers a glimpse into this beautiful thoroughfare’s past. As you’ll see, the avenue and its surrounding buildings have undergone many minor nips and tucks over the years – along with a few major facelifts.

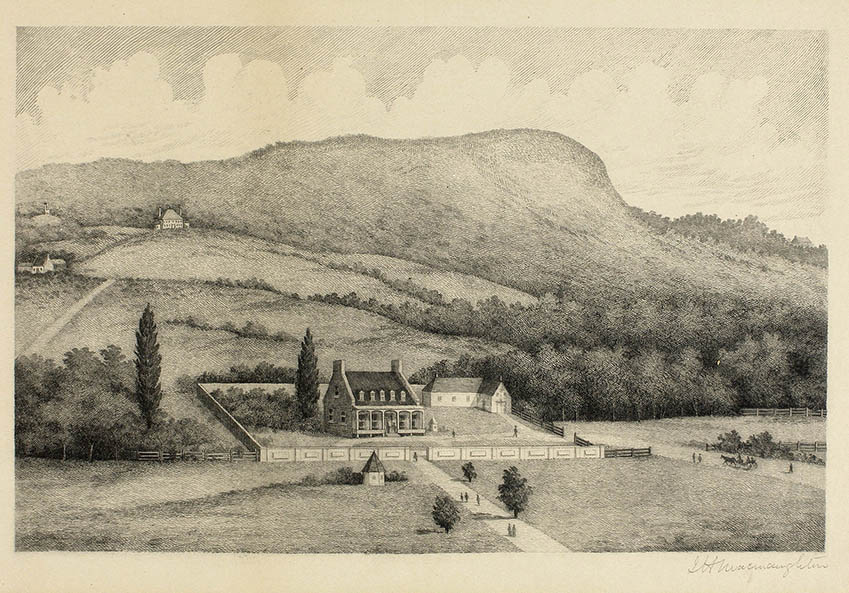

1. DILCOOSHA, JESSE JOSEPH’S HOUSE

The McLennan is McGill University’s largest library. It was built between 1967 and 1969 on the site of this Montreal mansion, which served an interesting variety of purposes over the years. Constructed in about 1865 in the Egyptian Renaissance style, it was named Dilcoosha (Hindustani for “Heart’s Delight”) by its first owner, the Montreal businessman Jesse Joseph.

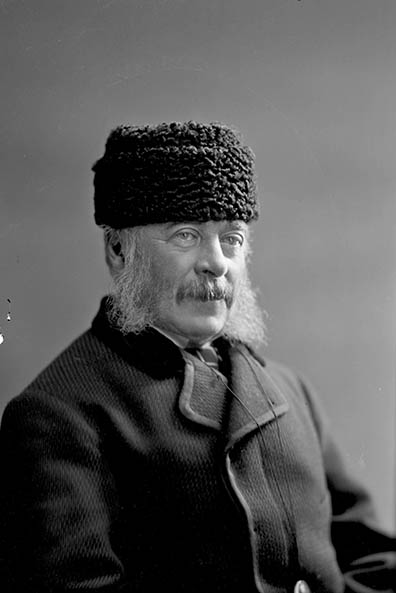

Jesse Joseph (1817-1904) was a busy and successful man. President of the Montreal Gas Company and the Montreal Street Railway Company, and director of the Great North West Telegraph Company and a number of banks, Jesse Joseph also invested in real estate and built Montreal’s Theatre Royal. In addition, he served for over fifty years as the diplomatic representative for Belgium in Montreal. Jesse Joseph was also a kindly and benevolent donor, whose gifts to charities were often anonymous, as he disliked “anything savouring of notoriety.” A longtime board member of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, located on McGill College Avenue just around the corner from his house, Jesse Joseph was president of the congregation at the time of his death in 1904.

After his death, Dilcoosha was purchased and donated to McGill by Sir William Macdonald, to prevent a hotel from being built on the lot. During World War I, the Joseph house was used by the McGill contingent of the Canadian Officers’ Training Corps, and a firing range was set up in the attic!

Jesse Joseph était également un donateur généreux et bienveillant dont les dons à des organismes de charité étaient souvent effectués sous le couvert de l’anonymat, car il abhorrait « ce qui sentait la notoriété ». Membre de longue date du conseil d’administration de la Synagogue espagnole et portugaise, située sur l’avenue McGill College non loin de sa maison, Jesse Joseph était président de la congrégation au moment de sa mort en 1904.

Après sa mort, Dilcoosha fut acheté et donné à McGill par Sir William Macdonald, pour empêcher la construction d’un hôtel sur le site. Pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, la maison Joseph fut utilisée par le contingent du Corps-école d’officiers canadiens de McGill, et un champ de tir y fut aménagé au grenier!

In 1919 David Ross McCord (1844-1930) donated his collection of some 18,000 objects relating to the history of Canada to McGill, along with an endowment. The McCord National Museum was officially opened in Dilcoosha on October 13, 1921. Housed there for over thirty years, the museum was moved in late 1954, when the building – which had developed a large crack in the rear wall – was condemned and slated for demolition.

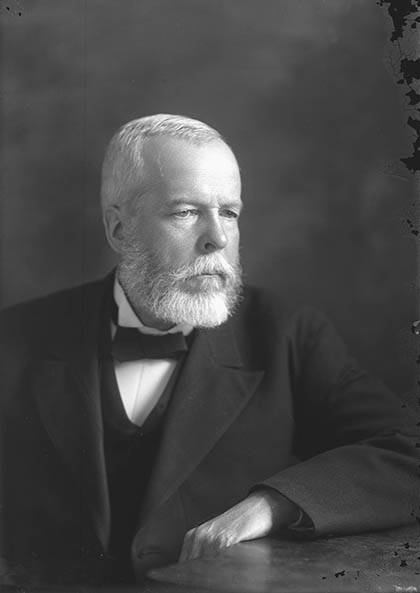

David Ross McCord was born in Montreal, the son of lawyer John Samuel McCord and his wife Anne Ross. After attending the High School of Montreal, he completed his education at McGill University, earning a BA in 1863 and a law degree in 1867. Though he practised as a lawyer, by the 1880s David Ross McCord’s hobby of collecting material related to the history of Canada had developed into a passion.

2. MRS. PAUL’S HORSES AND CARRIAGE

McGill University’s gatehouse was built in about 1868. This stone structure, which had walls more than half a metre thick, was for over three decades the home of McGill’s guardian, John Herbert and his family. Herbert’s successor, groundskeeper Thomas Graydon, lived there from around 1902.

Unfortunately, the house was damaged by blasting for the Canadian Northern Railway tunnel, constructed between 1912 and 1918. The floors sank in 1915, rendering the building uninhabitable, and it was demolished in 1920.

3. RODDICK GATES

Designed by architect Grattan Thompson and built in 1924 by the Anglin-Norcross construction company, these gates were a gift to McGill University from Lady Amy Roddick, in memory of her husband Sir Thomas George Roddick.

A punctual man, Thomas George Roddick (1846-1923) had often told his wife that he thought McGill should have a central clock for its students. Accordingly, the gates were flanked on the left by a six-metre-high clock and bell tower, with four clock faces and four brass bells to mark the hours.

Roddick graduated from McGill in medicine in 1868, the valedictorian of his class. After beginning his surgical career at the Montreal General Hospital, he became professor of surgery at McGill and later dean of medicine. Roddick was appointed chief of surgery at the Royal Victoria Hospital when it opened in 1894.

He was granted a knighthood in 1914 for his efforts in promoting the Canada Medical Act, which established the Medical Council of Canada to standardize medical education and the registration of graduates.

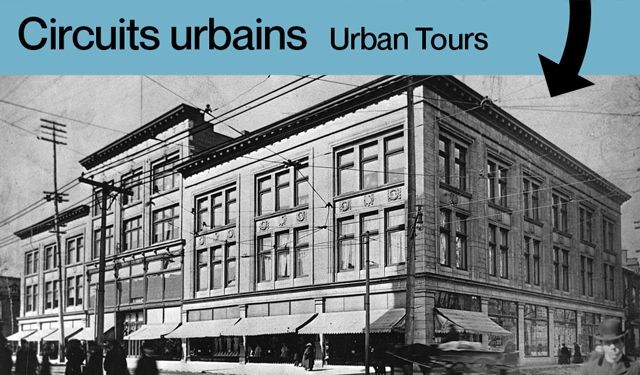

4. Y.M.C.A BUILDING

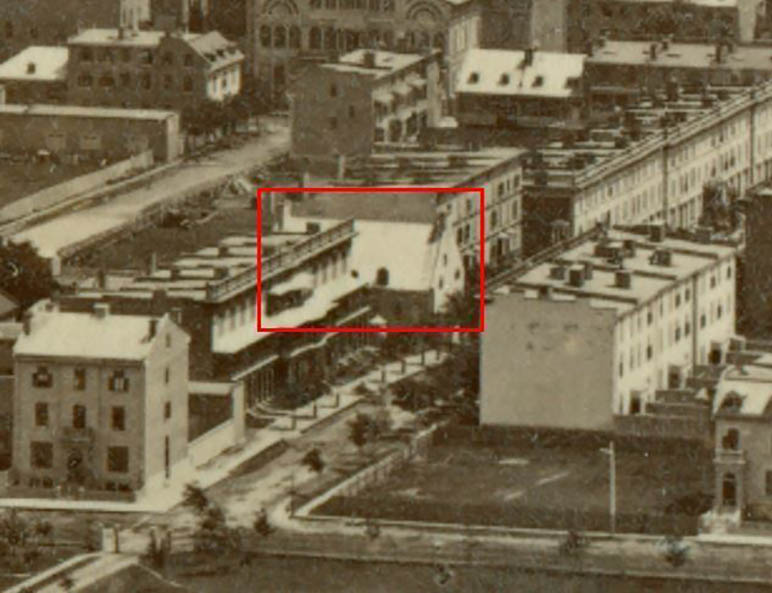

When this photograph was taken, the building was home to the McGill Y.M.C.A. For most of the previous two decades, however, it had been an educational establishment known as Bute House, operated by the McIntosh sisters. According to an advertisement, the school was “situated in one of the healthiest and most beautiful parts of the city.”

Prior to constructing Bute House in 1864, the Misses McIntosh had run an academy for young ladies a few doors down the street in Burnside, James McGill’s former farmhouse.

At Bute House, day students and boarders were taught by Annie, Isabella, and Annabella McIntosh, and their mother, Mrs. Neil McIntosh, was also involved in running the school. In 1873 the establishment was taken over by Mrs. Robert M. Watson.

This picture shows Isabella and Annabella McIntosh in 1881. The two sisters had retired from teaching at Bute House in 1873, possibly in order to look after their ailing mother, who died of consumption in 1874.

By December 1901, McGill Y.M.C.A. membership had increased to the point where Sunday meetings had to be held in the Redpath Museum, since there wasn’t enough room in the Y.M.C.A. building for everyone to assemble at once.

Plans were made for a new, larger facility, and Strathcona Hall was officially opened in October 1905. When the Place Mercantile office tower was under construction in the early 1980s, Strathcona Hall partially collapsed and was completely rebuilt.

Today, this building is occupied by the Cascades company.

5. GATES TO MCGILL UNIVERSITY

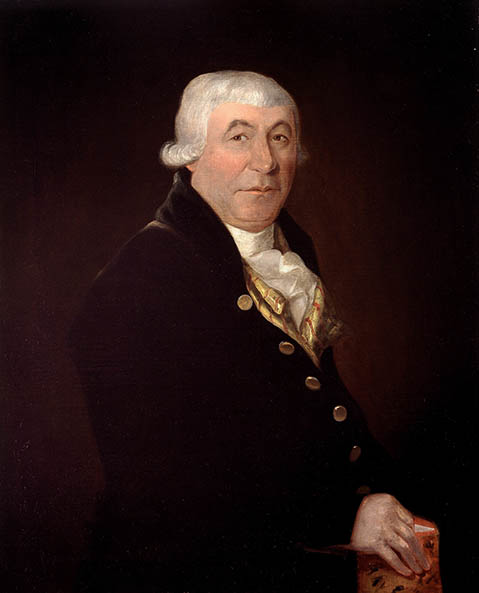

McGill University was founded after wealthy merchant James McGill (1744-1813) died and bequeathed his 46-acre country estate, Burnside, to the Royal Institution for the Advancement of Learning, on the understanding that it become the site of an institution of higher education. The establishment of the university was fraught with legal difficulties, but McGill College was finally inaugurated in 1829 and its first faculty, that of Medicine, officially opened.

The University of McGill College (the title that was often used for the insititution before 1885) struggled financially in its early years, and it was not until 1843 that the two buildings seen in the second photograph were constructed and the Faculty of Arts established.

James McGill’s Burnside estate originally extended from what would become Dorchester Street (now René-Lévesque Boulevard) northwards to a little below present-day Docteur-Penfield. On the west side it was bounded by University Street (now Robert-Bourassa), and on the east it stopped just short of present-day McTavish Street.

In an effort to raise money for the college, authorities decided to lease and then later sell outright the land south of Sherbrooke Street. A plan was drawn up that divided the property into small lots and added roads, and so McGill College Avenue came into being.

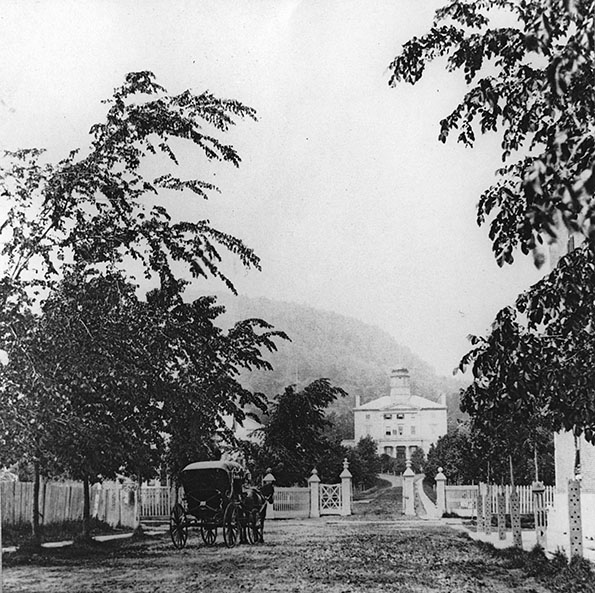

In 1869, John William Dawson had been Principal of McGill for fourteen years. Dawson took a particular interest in improving the grounds, which when he arrived had been “unfenced, and pastured at will by herds of cattle.”Beyond the well-kept wooden fence and gate at Sherbrooke Street, the trees he had carefully planted – mere saplings in 1859 – have begun to fill out along the avenue.

6. DAVIES SCHOOL OF INTERIOR DECORATION

According to the Wm. Notman & Son Ltd. studio records, this photograph was commissioned by the Laurentide Construction Company, likely the contractors for the office building. Not long after it was completed in 1931, the building’s tenants included a bookshop and lending library, a radio dealer, a plumber, a designer and maker of electrical fixtures, and the Davies School of Interior Decoration.

W. H. Davies had been an interior decorator for thirty-five years when in the fall of 1931 he opened the school in his new studio. Davies’ advertisements claimed that his classes would “assist those who desire to qualify as Interior Decorators, or to fit up and maintain their homes in a distinctive and artistical manner.”

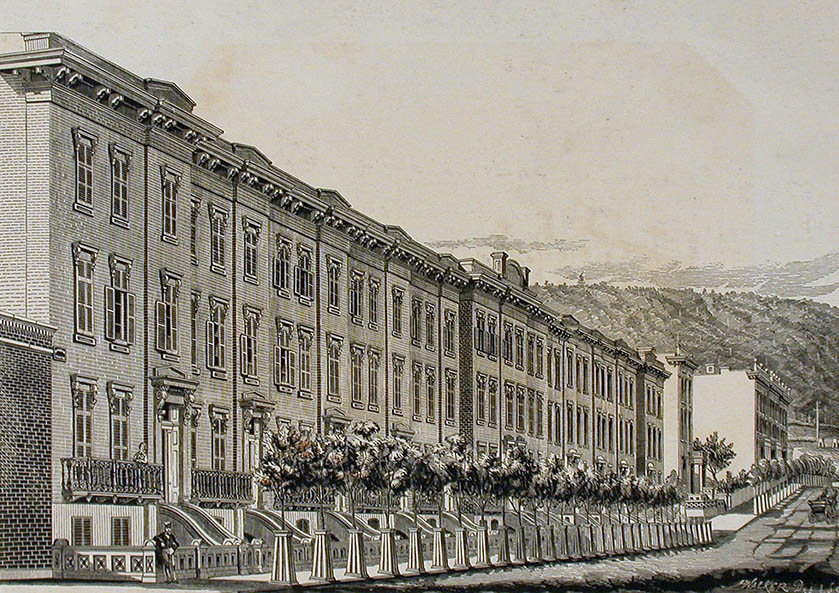

7. MCGILL COLLEGE AVENUE, LOOKING SOUTH

In 1869, McGill College Avenue was a prestigious place to live, lined on either side with fashionable row houses, or “terraces,” styled after the townhouses common in cities such as London or Edinburgh.

The quiet, residential character of the avenue at this time was no accident. In the 1850s, when sales of lots on McGill College lands below Sherbrooke Street were being promoted, strict rules were imposed on buyers: no industrial premises were allowed, nor were any activities permitted that were “likely to disturb or discourage neighbours – such as stone masons’ yards or tanneries or other noisome trades.”

8. SHAAR HASOMAYIM SYNAGOGUE

The word ”synagogue” is of Greek origin, and refers to a congregation in a city or neighbourhood. In concrete terms, it means a place where members of the Jewish community gather for prayers, celebrations and religious instruction. The Shaar Hashomayim synagogue is one of Montreal’s oldest Jewish congregations.

It was founded in 1846 by English, German and Polish Jews who originally met in a rented space on St. James Street (today Saint-Jacques). The Shaar Hashomayim synagogue has moved three times. The first was built in 1859 at 41 Saint-Constant Street (now De Bullion), south of De La Gauchetière. In 1885 the cornerstone was laid for a new synagogue at 59 McGill College Avenue, which was inaugurated the following year and served the community until 1922.

During this period, the congregation was opened to all forms of Judaism. By 1920 the growing community had become rather constricted in its McGill College Avenue building, and it purchased land to build the current synagogue in Westmount.

Before the McGill College synagogue was constructed, the site was occupied by James McGill’s farmhouse, Burnside. McGill enjoyed spending summers on his estate, which during his lifetime was situated well outside the city. By the time his house was demolished in about 1875, the idyllic scene with open fields portrayed in the picture had long since disappeared.

James McGill’s Burnside farmhouse is visible in this photograph from 1865, appearing a little out of place in McGill College Avenue’s otherwise orderly urban landscape of row houses.

9. TOWNHOUSE, MCGILL COLLEGE AVENUE

Between 1886 and 1892, Miss Maria Charlotte Gee, a nurse and masseuse, lived here at 40 McGill College Avenue, on the corner of Burnside Place (now De Maisonneuve Boulevard), in one of a row of houses called Mount Royal Terrace.

During that time she opened a private hospital, enlarging her premises by also taking over the neighbouring terrace unit to the south (number 38). According to an 1890 newspaper advertisement, Miss Gee’s Private Hospital & Nursing Institution could also supply “English trained nurses” for clients “in or out of the city.”

10. TERRACE HOUSES ON MCGILL COLLEGE AVENUE

Mount Royal Terrace, consisting of twelve three-storey brick-faced townhouses, each with thirteen rooms plus pantries and baths, was constructed between 1858 and 1859 by Henry Bulmer.

Those who purchased a home at this upscale address were often comfortably established in lucrative professions and had the means to employ two or three live-in servants. Among the first inhabitants of the terrace were a number of prosperous merchants, a broker and a hatter.

The house at the far end of the terrace, where Miss Gee would later set up her hospital, belonged first to Alexander Walker, a wholesale dry goods merchant.

These two images show wholesale hardware merchant John Caverhill, his wife Mary Jane Sibley and their son Frederick Thomas Caverhill, longtime residents of Mount Royal Terrace.

11. MONTREAL VIEW

McGill College Avenue’s present commercial character had already developed by the time Albert Edward Cloutier created this painting in 1951. The office building on the right, stretching from Cathcart to Sainte-Catherine Street, is the Confederation Building, constructed in 1927-1928.

The lovely view of the Mountain afforded by McGill College Avenue was almost obliterated in the mid-1980s, when a developer made plans to build a symphony hall and shopping complex that would have closed off the street. Thanks to the work of heritage conservation advocates, this project was abandoned, and McGill College Avenue was widened and upgraded instead.

In the foreground of the painting can be seen the entrance to the train tunnel that runs under the mountain to the Town of Mount Royal. In 1951 this entrance would have been situated just behind you, on your right. It was covered over by the Place Ville Marie complex, whose construction began in 1959 and which was officially opened in 1962.

The Canadian Northern Railway project, begun in 1912, was a feat of engineering at the time. Tunnels were excavated from both sides of the mountain, and reportedly the alignment was out by only a few centimetres when they met in December 1913.

The train tracks were not opened to regular traffic until 1918, as difficulties arising from World War I had hampered the project’s completion.

A little over a century later, the tunnel is still very much in use, although some much-needed renovations prior to introduction of the new REM light rail line will disrupt service for a time, beginning in 2020.