Welcome to the Studio

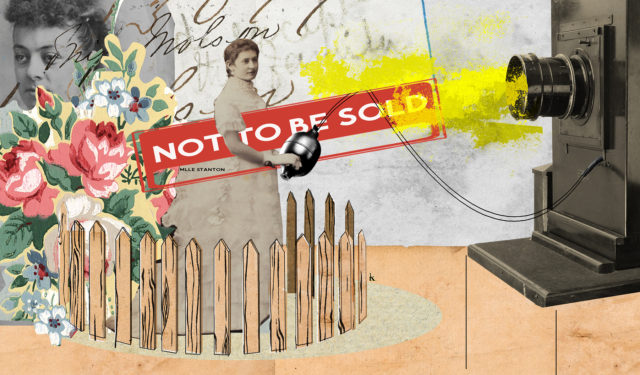

Not to Be Sold: Privacy at Notman’s Studio or Controlling One’s Image in the 19th Century (Part 1 of 6).

June 28, 2022

The complexity and cost of early photography processes meant that the vast majority of 19th century photographs were produced by commercial photography studios, which were especially common in North America’s industrialized and urbanized northeastern region.

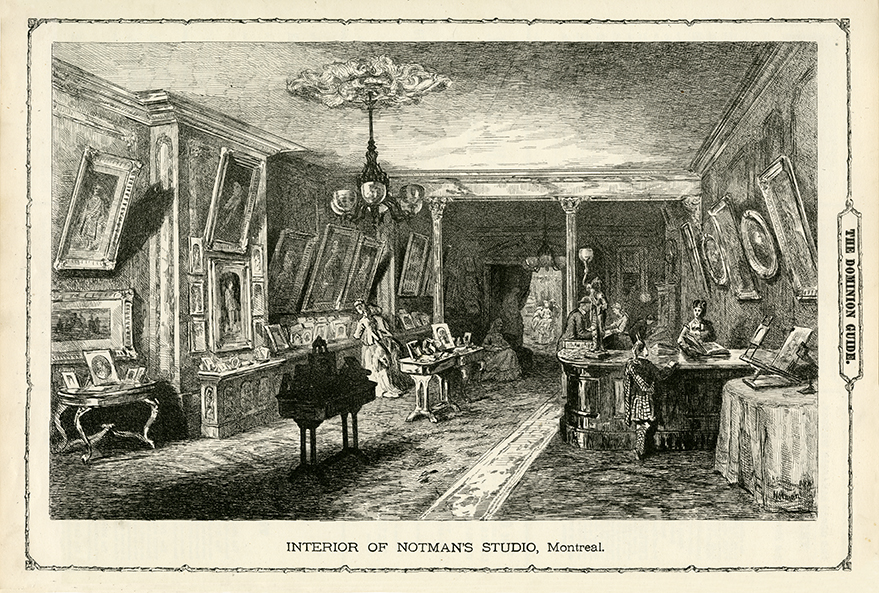

Published in an 1872 issue of The Canadian Illustrated News, this lithographic image gives a sense of what the reception room of William Notman’s Montreal studio looked like and offers insight into some of his studio’s practices.

DÉCOR

The décor of the reception room portrayed by Sandham reflects the practices of commercial studios, which attracted customers with the trappings of domestic style and comfort. The lithograph shows that the reception room was decorated like an elegant parlor room.

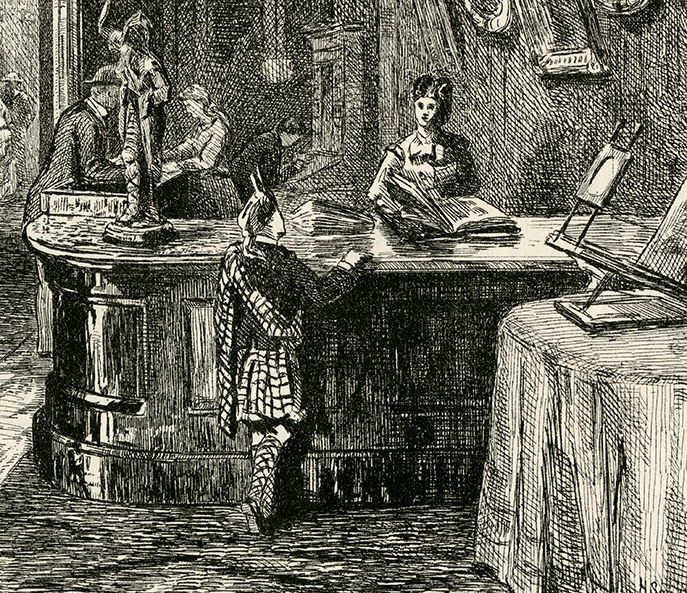

In the right-hand corner of the image, we see a table draped with a tablecloth and set with a stereoscopic viewfinder for the enjoyment of prospective clients. Just beyond the table, a female employee at the counter engages with a boy in Highland dress. She is flipping through a large book, which likely included additional photographs for sale. Views of Canada, for example, were popular among locals and as souvenirs for visitors to the city. On the tabletops are framed portrait photographs, while the walls are hung with paintings and further exemplars of Notman’s portraiture.

This elegant, welcoming public display, which included what we usually think of as private portraits, was completely in keeping with both the faux domestic décor and the marketing strategy of early commercial photography studios.

EXHIBITING SAMPLES

Studios were in the habit of exhibiting samples in order to generate business. Many early photography studios in city centres were located on the top floor of commercial buildings due to their dependency on natural light, so it became common to market photography services by installing portraits and other photographs in glass cases at street level to lure clients.

Documents from this era suggest that it was not necessarily the norm to request permission from sitters before exhibiting their likeness, especially those with some degree of public renown. In 1849, a young writer named Sara Lippincott, who wrote under the pseudonym Grace Greenwood, happened upon her own portrait at the door of the famed Southworth & Hawes studio in Boston. Nancy Hawes was managing the studio at the time and recounted with much relief that Greenwood admired the image and “did not even request to have it taken away!”1

PUBLIC AND PRIVATE

Histories of privacy usually point to the arrival of the handheld camera in the 1880s as the moment when photography began to pose a threat to privacy. However, the commercial display of studio portraits points to one way that photography muddied the boundaries between public and private even before the era of the snapshot.

Notman’s studio reception space was designed in part to allay anxieties about photography and its commercialization by combining signifiers of private or domestic décor with public modes of display. While most clients seem to have been mollified, Notman’s Picture Books provide fascinating evidence that some clients were, in fact, concerned about privacy.

KEEPING TRACK

Like other commercial photography studios of the era, Notman and his staff developed a system for keeping track of the photographs taken in the studio. What is unusual is that Notman’s studio records have survived intact, providing a rare window into the early dynamics between studio and clients.

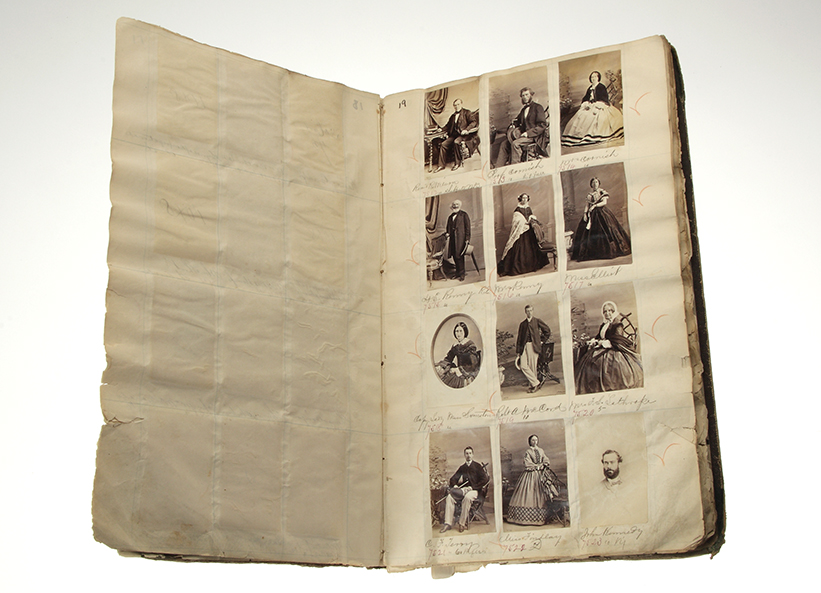

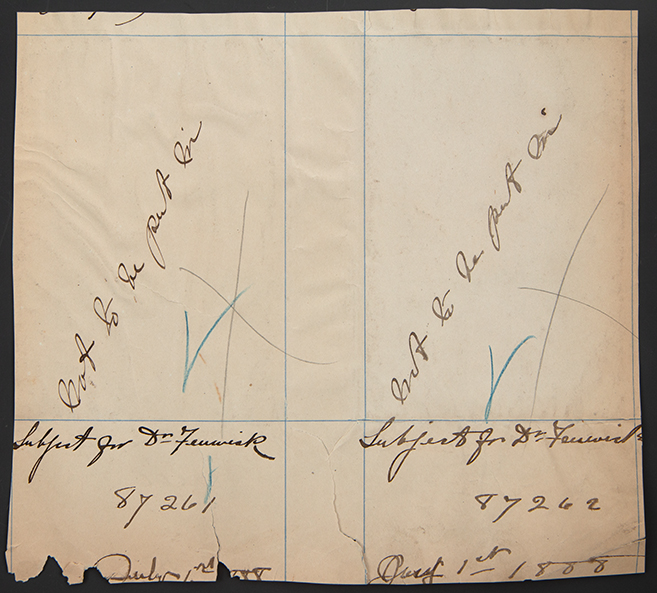

At Notman’s, portraits were archived in a ‘Picture Book’ and annotated with the sitter’s name and the corresponding negative number. The series of Picture Books formed an essential clerical tool of the studio, recording information that Notman’s staff needed to fulfil orders.

From notations in the books, we know that some clients dictated restrictions on the circulation of their photographs to Notman’s staff, who dutifully annotated the pages of the Picture Books with stipulations regarding whether copies of the portrait could be sold and to whom.

In turn, these restrictions point to fact that it was understood that people other than sitters and their families might purchase or attempt to purchase copies of studio photographs. In a few cases, notes appeared in the Picture Books indicating that copies of some photographs should “not be put in,” revealing an even more forceful effort to protect the portrait subject, even from the eyes of Notman’s staff.

CASE STUDIES

In a series of five articles, we will examine photographs taken at the Notman studio in the 1870s and 1880s. In each case, we will consider the anxieties that might have led Notman’s clients to apply restrictions to their portraits in an attempt to gain some control over the images and limit their visibility.

These attempts of sitters to exert control over their photographic likenesses are akin to contemporary concerns regarding privacy and social media photography. The restrictions placed by sitters on the photographs taken at Notman’s suggest that the tension between commercial and individual interests in today’s media landscape has deep historical roots.

NOTE

1. August 24, 1849, Letter from Mrs. Hawes to Mr. Southworth, Southworth & Hawes Records. Alden Scott Boyer Collection. Richard and Ronay Menschel Library, George Eastman Museum.

The series Not to Be Sold: Privacy at Notman’s Studio is supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.