What’s in a Title?: Researching a Notman Studio Photograph

The surprising story behind a mysterious photograph from the Notman Studio.

March 15, 2017

This image has intrigued staff and a number of researchers visiting the McCord Museum over the years. Dated 1924, it belongs to a section of photographs from the Notman Studio that was never fully catalogued. It was given the title Altar for Miss Adair following the inscription found on the negative envelope. As was the custom in the past for negatives of potential interest to researchers, a modern contact print was made and placed in the “working files” for consultation by visitors. Years later, it was scanned and the digital file was linked to the McCord’s website in an early digitization project.

The photograph shows a framed portrait of a soldier, hanging above a makeshift altar with a line of lighted candles placed along a fireplace mantle. With the Altar for Miss Adair title, the uniformed soldier, and the date of 1924, it is not difficult to conjecture stories of a boyfriend or fiancé, lost in the Great War and still mourned six years or so afterwards. The photograph could be seen as symbolic of a generation of young women who would not see the return of their loved one at the war’s end.

At least that’s what we had always assumed!

I first noticed a problem with this storyline last spring. A generous grant from The Molson Foundation had allowed the Museum to digitize a great number of the deteriorating nitrate negatives, most of them as yet uncatalogued in our database. Among these images were four sequential ones directly preceding the altar photograph. Never printed for our “working files”, and not yet catalogued in our database, these images had not been connected with the altar image in the recent past. The negative just prior to the altar image shows a man and woman standing in front of the same altar. She’s in a wedding dress, and the negative envelope was labelled simply “Miss Adair.”

Hmmm! I thought, and vowed to research it further someday, when time permitted.

Happily, in December, before the year was out, a client who had visited us a couple of decades ago and taken home a photocopy of the altar image wrote to ask if we had any information on who Miss Adair was, or where the photograph was taken. It was my absolute pleasure to take on the challenge!

First step: examine the Notman Studio’s original record-keeping tools, to check for more clues to Miss Adair’s identity. Notman’s staff kept a careful record of the sitter’s name, with sequential numbering for each photograph they sold. The client’s surname was recorded in two books, an alphabetical index book for finding the photograph number, and a “picture” book in which the photographs were pasted numerically, with the client’s name underneath. An examination of the picture book and index book rewarded me with some very useful information—Miss Adair’s first name began with an “L” and, most importantly, the title of the altar image was not Altar for Miss Adair, but rather Altar at Mrs. R. Adairs.

That changed things a little bit. Perhaps Mrs. R. Adair had lost a son in the war. With this title, the photograph could instead be seen as a symbol of the plight of so many mothers during the Great War—the loss of a whole generation of sons who died entirely too soon, their absence keenly felt by their surviving parents.

Now, a quick bit of research to find the full name of Miss L. Adair, the location and date of her wedding and, “case closed,” I would write up a summary for the client. One small problem cropped up rather quickly in the research process, however—Mr. and Mrs. Robert Adair didn’t have a daughter! It turns out that Miss Lilian Maude Milroy Adair’s deceased father John was Robert Adair’s brother, and thus it was at her uncle’s house at 18 McTavish Street that she was married, on May 31, 1924, to a Dr. Charles C. Stewart.

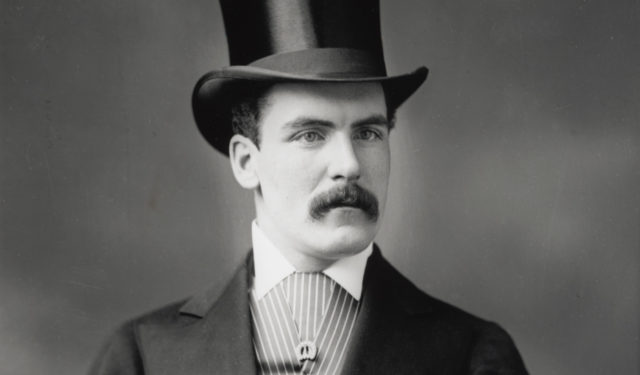

So who was the soldier pictured above the fireplace altar? A look in the “A”s in our index books for the WWI period demonstrated that the Adairs were indeed very good customers of the Notman firm. The original portrait was taken in 1915, and features Mr. & Mrs. Robert Adair’s son, Robert Alexander Shearer Adair, just before he left Canada to go to war.

There’s one final hitch in the presumed story. Robert Adair fils did not die in World War I. He returned to Canada, and took up a position in his father’s business, becoming Director of the Hartt & Adair Coal Company. He did, however, die suddenly at his home on August 23, 1923, the year prior to Miss Adair’s wedding. He was 29.

So the photograph of an altar with a soldier’s framed portrait, in the end, does not memorialize or symbolize any of the things that we once thought it did. It is not a photograph of a shrine created specifically to honour a soldier who fell during the first World War, nor was it taken for the soldier’s bereaved girlfriend. It is definitely a lesson in how the title of a photograph can have a very strong influence on what the viewer perceives to be its subject and meaning.