Temporary Exhibition

From October 20, 2023 to March 10, 2024

Wampum: Beads of Diplomacy

A Canadian Exclusive

Wampum are remarkable objects made from shell beads that were exchanged for over two centuries—from the early 17th to the early 19th century—during diplomatic meetings between nations in northeastern America, including European nations. For the first time, this unprecedented exhibition brings together over 40 wampum belts from public and private collections in Quebec, Canada and Europe. Some forty cultural objects from the period also help to contextualize and explain their fundamental role.

The participation of contemporary Indigenous voices in the exhibition highlights the continuing importance of wampum in Indigenous cultures today. Discover the work of artists Hannah Claus, Nadia Myre, Teharihulen Michel Savard and Skawennati, inspired by wampum, and hear stories from members of several nations through a series of videos.

Powerful cultural and political symbols in Indigenous societies, wampum contain messages and knowledge that need to be heard. As material witnesses of the sacred principles and agreements that bind nations, these precious objects are the bearers of stories and should be better understood. The exhibition invites you to understand the fundamental role of wampum in relations between Indigenous and European nations, the relationship between these objects and geopolitical issues in Canadian history, and their significance and influence today.

This exhibition is made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art.

This project is funded in part by the Government of Canada, with the support of the Consulat général de France à Québec.

3 things to know

Over 40 wampum belts brought together

Developed and co-produced with the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac in Paris, the exhibition was first presented in Paris and then at the Seneca Art and Culture Center in Victor, New York. The only stop in Canada, the Montreal presentation brings together the largest selection of cultural belongings: it includes 13 wampum from the McCord Stewart Museum collection, as well as the wampum belt presented by the Kanesatake community to Pope Gregory XVI, which has not been repatriated since 1831.

In the exhibition galleries, you will also be able to view wampum and related objects – medals, weapons, ornaments, moccasins, maps, engravings, books, etc. – from the McCord Stewart Museum collection, as well as from the collections of the Canadian Museum of History, Parks Canada, the Bank of Canada Museum, the Musée de la civilisation, the Centre d’Archives Régionales du Séminaire de Nicolet, the Musée Huron-Wendat, the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac in Paris and the Trésor de la Cathédrale de Chartres.

The physical representation of words

Wampum belts are the physical embodiment of the spoken words, pacts or laws associated with all agreements or discussions between nations. Spoken words were only considered sincere if accompanied by wampum. These “belts of truth” therefore served to materialize the word, to confirm it and to seal alliances.

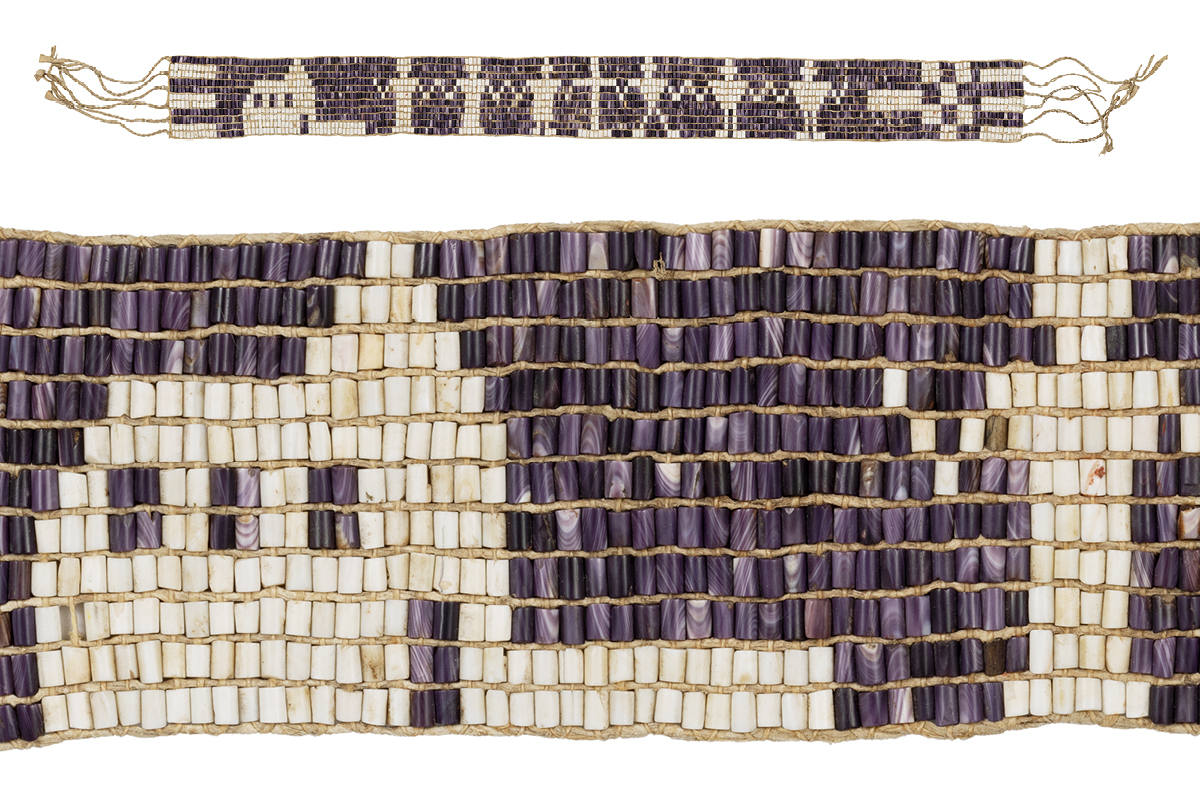

The beads were arranged in various patterns that represented specific things, helping those involved remember what was said. The more beads used to make a wampum, the more important its message. This international protocol regime was adopted by the Europeans, who used wampum strings and belts in their diplomatic negotiations with First Nations until the early 19th century.

Made from marine shells

Wampum are made from marine shells found on the east coast. These shells are purple and white. The production of wampum beads from the purplish lip of the bivalve shell, which is very thick and difficult to pierce, only really began with the introduction of metal tools by the Europeans. The lip is broken into sections, which are then cut into tubes and drilled. The growing demand for wampum beads in the 18th century encouraged manufacturers to use the remaining shell to produce white beads. Despite the use of European metal tools, it is estimated that a craftsman produced an average of 42 beads a day.

So it’s not hard to imagine why a wampum belt with 10,000 beads would be worth so much, and why some European nations have attempted to produce wampums with glass, porcelain, ivory or marble beads. The beads are held together by a variety of materials, such as plant or animal fibres (like hemp or sinew). Some beads are painted with red pigments (red ochre or vermilion).

Learn more about wampum

Wampum or wampums?

It’s important to distinguish between “wampum” and “wampums.” When we speak of “wampum” as a mass noun, we’re referring to the raw material, i.e. the beads. On the other hand, when we speak of “wampums,” we’re referring to wampum belts, which are in fact bands of several strands of woven beads. The French called wampums “colliers de porcelaine” and the English “wampum belts.” These two expressions identify the same object exchanged during official diplomatic meetings. Note that a belt is not the same as a “string of wampum,” the latter consisting of beads strung on a single cord. Strings were exchanged, on their own or tied together to form a unit of several hundred beads.

Is it a wampum necklace or belt?

In the French literature on wampums, we sometimes hear the expression “ceinture de porcelaine,” which is in fact a translation of the English “wampum belt.” Yet in French archives, wampums are always referred to as “colliers de porcelaine” (porcelain necklaces), and the French exchanged these necklaces in the same way that the English exchanged “wampum belts.” Some English translations of French sources have often translated the word collier as “collar,” adding to the confusion.

Is it jewelry? An ornament? A belt?

Wampum beads were used to adorn objects and clothing, and to create ornaments (cuffs, pendants). Wampums are not really necklaces or belts; they are not garments. It was around 1870-1930 that some chiefs began wearing them (especially among the Wendat).

To learn more about the translation issue, watch Jonathan Lainey’s presentation for McCord Stewart Discoveries.

Do Indigenous nations still produce wampums?

Wampum belts have not been officially produced or traded since the early 19th century. Reproductions of wampums are made today. They were in production until the War of 1812. After the Anglo-American war, the balance of power available to Indigenous nations withered away. Their military weight is gone, and the written word has gradually replaced wampum. Indigenous leaders will sometimes demand paper copies of treaties and agreements signed with Europeans.

What is a votive wampum?

Votive wampums are wampums that have been presented by Indigenous communities to religious communities, and on which Latin texts have been woven. Of the dozen or so produced since 1654, only 3 votive wampums have survived to the present day. All three are presented in the exhibition.

Learn more about ownership and property rights

Have wampum belts been stolen from communities?

Given the nature and function of these objects, it’s safe to assume that most of the wampum belts preserved in Europe were voluntarily given by the Indigenous nations at the time of the initial exchange. In Canada and the United States, individuals from Indigenous communities, sometimes elders, chiefs or descendants of chiefs who have inherited wampums, have sold or donated them to amateur or professional collectors (antique dealers, numismatists or anthropologists).

The sale or acquisition of wampums by collectors may raise questions about the consent of individuals in communities to sell wampums. According to the Moved to Action report by the Canadian Museums Association (p. 53): “The presence of duress calls into question the voluntariness of an acquisition. Duress is defined by one of the participating parties of any trade of goods or intellectual property being forced to act against their will or better judgement due to threat, violence or societal constraint.” This notion of duress must therefore be taken into account when considering the ownership of museum objects.

Many cultural goods have been legally acquired by collectors. However, given the context in which Indigenous people lived at certain times, it’s important to ask whether selling objects of great spiritual value to collectors was not simply a question of survival. There are several examples of wampums that were pawned by their guardians and subsequently not recovered for lack of funds.

In other cases, we know that wampums have been seized by law enforcement agencies. In 1924, on behalf of the federal government, the RCMP seized the wampums kept by the Six Nations of the Grand River.

Are we able to verify the method of acquisition by collectors?

It is sometimes possible to trace the acquisition back to the original collector. However, it is often difficult, if not impossible, to determine whether the sale was made under duress. Given the highly symbolic and spiritual nature of wampum, it’s reasonable to assume that this was not done in the complete absence of coercion.

- The method of collection is rarely clearly indicated, nor is the precise source. The objects were often sold without the authorization of the community or chiefs, which could make the legitimacy of the transaction questionable today.

- One of the reasons for the sale of these objects is the change in modes of ownership, which gradually shifted from the collective and national domain to the individual and family sphere between the late 19th and early 20th century.3

- We know that some wampums have been bequeathed or sold in order to benefit from better preservation conditions, particularly in the United States. Fearing their eventual dispersal or slow destruction, some chiefs have placed their wampums in universities or national museums, which they have officially designated as “wampum custodians.”

How were the wampums in the Museum collection acquired?

Most of the wampums in the collection were sold by David Swan to David Ross McCord in the early 1900s. Swan was a Kanesatake individual who was also present in the Georgian Bay region of Ontario. He acquired objects for McCord in these regions (Georgian Bay, Toronto, Lake Huron) and around Montreal.

Do we know the nations of origin of the wampums in the exhibition?

Of the 40 wampums featured in the exhibition, we know that one comes from the Abenaki, ten from Wendake, and four from Kanesatake. The origin of the other wampums remains unknown.

Were the wampums made only by Indigenous communities?

Wampum belts are not just an Indigenous product. Some were produced and given by the British and French during exchanges with Indigenous communities. To find out more, read this article by Jonathan Lainey on the Museum’s Blog: Europeans and the use of wampum belts.

Learn more about this exhibition

Why present a wampum exhibition at the Museum?

- To take advantage of a unique opportunity: an exhibition on the subject produced by the MQB is on tour.

- The McCord Stewart Museum owns 13 wampums, the largest collection in a Canadian museum.

- Jonathan Lainey was part of the research committee for the exhibition presented at the MQB: https://croyan.quaibranly.fr/en/exhibition-wampum-beads-of-diplomacy-in-new-france

- The Indigenous Cultures curator’s expertise on the subject.

The aims of this exhibition are:

- To deepen the Museum’s scientific knowledge on the subject and to make wampum belts better known (among the general public and within Indigenous communities).

- To reinforce the importance of objects that bear witness to the alliances on which the country was founded (recognition of their importance), to explain their role and to talk about their current relevance.

- Local collections (from Ontario/Quebec) are less well known than those from the USA: to bring them to light, out of the shadows.

- To identify them, group them together, make them accessible: important, precious, coveted objects that are rarely exhibited.

- To engage in discussion and reflection.

- To bring people together, creating opportunities for encounters, peace and friendship (again, as wampums used to do).

Were Indigenous nations involved in producing the exhibition?

The content of the exhibition was co-developed by a research committee made up of Indigenous curators/experts on the subject (Jonathan Lainey and Michael Galban), and involved the help of Indigenous researchers Jean-Philippe Thivierge (historian and member of the Huron-Wendat Nation), Darren Bonaparte (Ahkwesahsró:non historian and author) and Nicole Obomsawin (Abenaki), and the collaboration of nation representatives (for example, the Kanesatake Cultural Centre and Band Council).

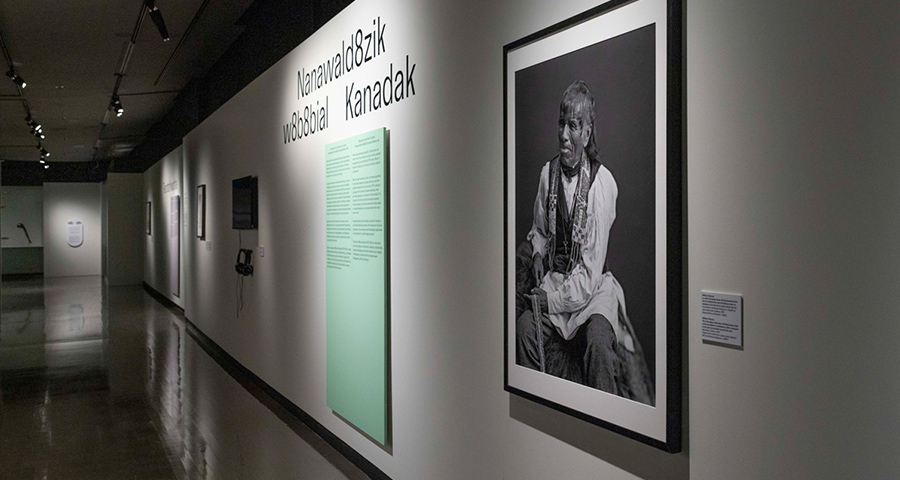

We’ve also made sure to include Indigenous languages in the Mohawk, Wendat and Abenaki title translations, as well as in the Mohawk and Wendat voices that can be heard throughout the exhibition.

The provenance of wampums is known for only two nations/communities of origin: Wendake and Kanesatake. They took part in the exhibition and wrote labels for their objects where possible.

Before the opening of the exhibition at the McCord Stewart, the forty wampums were welcomed by the people of the Kahnawake Longhouse according to protocol, and 38 representatives of different nations (Mohawk, Wendat, Algonquin, Onondaga, Abenaki, Tuscarora) were present and able to connect directly with the wampums.

The Indigenous Advisory Committee created by the Museum in 2019 was also consulted at every stage of the exhibition production process.

Why aren’t all 11 Indigenous nations in Quebec represented?

- This is not an exhibition on the history of Indigenous nations in Quebec (as is the exhibition Indigenous Voices of Today: Knowledge, Trauma, Resilience), but an exhibition on specific objects.

- Not all nations have used wampum in their diplomatic relations.

- The exhibition is based on research by the Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac in Paris, which has worked with the Wendat, Seneca and Abenaki peoples.

- We collaborated with the communities of Kanesatake and Wendake, as some of the wampums come from these areas.

- We tried to add Anishinaabe voices and perspectives, but without success.

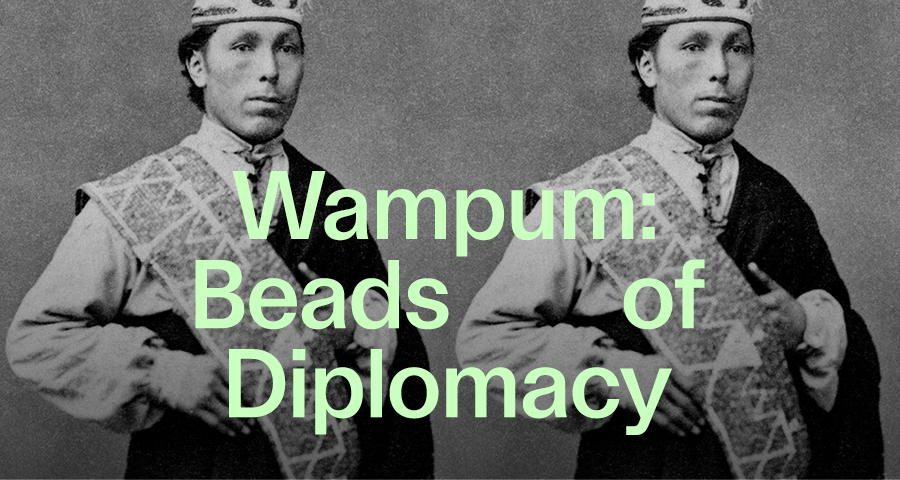

Who is the man on the exhibition poster? What’s the story behind his wampum?

Joseph Swan Onasakenrat was the brother of David Swan, who sold the Two-Dog Wampum to David Ross McCord in 1919 (the wampum pictured).

The son of Lazare Akwirente, Joseph Onasakenrat (known as the Swan or the White Feather) was a member of the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) community born on the Deux-Montagnes seigneurie in 1845. His childhood was marked by a climate of crisis between the members of his community and the Sulpician seigneurs. Joseph Onasakenrat was exceptionally intelligent and even surpassed his classmate Louis Riel, the future Métis rebel leader, in Latin at the Collège de Montréal. During this period, he saw the gap between the lavish lifestyle of the Sulpician priests, responsible for his education, and the extreme poverty of his village, governed by this same religious order. Back in Deux-Montagnes, where tensions were still high, he was viewed favourably by the Sulpicians, who encouraged his election as community leader in 1868.

To learn more, read this article by the MEM in the Journal de Montréal or consult the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

How does the Museum make the exhibition accessible to members of Indigenous communities?

- Access to the Museum is free for members of Indigenous communities (details here).

- School groups and Indigenous groups are welcome free of charge. Travel, accommodation and accompanying expenses are covered by Rio Tinto. As of November 6, 2023, 24 groups have planned to visit the Museum through this program.

- Free online workshop is offered to primary school children in collaboration with Cabane à culture. 53 classes across Quebec took part in the workshop (including a group from James Bay). Some 1,300 children have attended this workshop to date.

- An information booklet is offered free of charge to school groups in English, French, and Kanien’kehá:ka. Produced in collaboration with our Summer 2023 interns, Sakoianonhawi Curotte and Agatha Lambert. This mediation project was funded by Canadian Heritage.

Is there family content in the exhibition?

Labels for children and families have been placed throughout the exhibition to create a dialogue with children around the exhibition and facilitate their understanding.

Restitution requests

Could any of the objects in the exhibition be returned to the communities?

The Museum recognizes the rights of Indigenous communities to access their heritage. If we were asked, we would certainly be open to organizing a meeting to discuss the best place to store these important objects.

However, we cannot do anything or make any decisions regarding the many objects on display that come on loan from other institutions.

Are any of the objects in the exhibition subject to requests for restitution?

One of the wampums in our collection is the subject of a request. However, it is very preliminary. The source community knows that this wampum is here and that it is well preserved and accessible. Some people in this community prefer to wait until they have a safe place to preserve it before submitting the request.

Will any of the cultural goods presented be kept in the collections after the exhibition?

The cultural goods that were kept in our collection will be returned to our storage rooms. All objects borrowed from other museums and individuals will be returned to their owners/custodians/lending institutions.

Acknowledgements

The Museum would like to thank its team and all those who have contributed, in ways large or small, to the presentation of this exhibition

An exhibition by the McCord Stewart Museum, developed and co-produced with the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac in Paris.

Lead Curator for the Montreal presentation

Jonathan Lainey, Curator, Indigenous Cultures, McCord Stewart Museum

Associate Curators

Michael Galban, Curator of the Seneca Art & Culture Centre, Ganondagan State Historic Site, Victor (New York)

Paz Núñez-Regueiro, Head of the Americas Heritage Unit, musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Paris

Nikolaus Stolle, Visiting scholar for the CRoyAN project, musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Paris

Project Management

François Vallée, Project Manager, Exhibitions, McCord Stewart Museum

Exhibition and Graphic Design

Principal

Scientific Committee

Darren Bonaparte, / Ahkwesahsró:non Historian and Author

Jean-Philippe Thivierge, Huron-Wendat Nation

Lighting

Lightfactor

Impression

Graphiscan

Photographic Impression

Louis Lussier

Revision and Translation

Christine Dufresne (French)

Pascale Guertin (French)

Edith Skewes-Cox (English)

Multimedia Integration

Studio Kay

Collaborators

Kim Arseneault

Karine Awashish

Renaude Bastien

Valérie Bonspille

Victor Bonspille

Philippe Charland

Hannah Claus

Katsitsénhawe Linda Cree

Ka:nahsohon Kevin Deer

Tommy Deer

Valérie Dezelak

Fannie Dionne

Matthieu Gill-Bougie

Brad Gros-Louis

Heather Igloliorte

Johanne Lamoureux

Mgr Christian Lépine

Andrée Levesque Sioui

Megan Lukaniec

Philippe Meilleur

Mélissa Mollen-Dupuis

Nadia Myre

Kanerahtenhá:wi Hilda Nicholas Nicole O’Bomsawin

Lisa Phillips

Lise Puyo

Teharihulen Michel Savard

Skawennati

Yves Sioui Durand

Jean Tanguay

Leandro Varison

McCord Stewart Museum Team

Exhibitions

Geneviève Lafrance, Head, Exhibitions

John Gouws, Chief Technician, Exhibitions

Mélissa Jacques, Olivier LeBlanc-Roy, Patrick Migneault, Siloë Leduc, Joëlle Blanchette, Lyndon Polan, Philippe Bélanger, Technicians, Exhibitions

Stéphanie Poisson, cheffe, Head, Digital Outreach, Collections and Exhibitions

Anne-Frédérique Beaulieu-Plamondon, Coordinator, Digital Outreach, Collections and Exhibitions

Eric Fauque, Technical consultant – Multimedia

Conservation

Caterina Florio, Head, Conservation

Sara Serban, Conservator

Denis Plourde, adjoint, Conservation Assistant

Collections Management

Karine Rousseau, Assistant Head, Collections Management

Geneviève Déziel, Cataloguing coordinator, Collections Management

Camille Deshaies-Forget, Assistant, Collections Management

Roger Aziz, Photographer

Laura Dumitriu, Photographer

Josianne Venne, Senior Technician, Collections Management

Education, Community Engagement and Cultural Programs

Leïla Afriat, Project Manager, Community Relation, Education, Community Engagement and Cultural Programs

Marketing, Communications and Visitor Experience

Pascale Grignon, Senior Director, Marketing, Culture and Inclusion

Catherine Morellon, Head, Communications

Sabrina Lorier, Senior Officer, Digital Engagement

Philippe Bergeron, Officer, Digital Engagement

Marc-André Champagne, Officer, Public Relations

Sandra Nadeau Paradis, Officer, Publicity and Promotions

Anne-Marie Demers, Graphic Designer

Anne-Marie Beaudet, Head, Marketing and Visitor Experience

Lison Cherki, Coordinator, Client Development

Maïa Mendilaharzu, Coordinator, Membership and Visitor Experience

Antonin Gélinas, Head, Visitor services

Listen to stories from members of several nations to explore the powerful cultural and political symbolism of wampum.

Walk through the exhibition galleries.

What people are saying about it

« It’s a very wonderful, once-in-a-lifetime experience. It was amazing to be that close to our ancestors, to see all the belts that our ancestors made. » Hilda Nicholas, director of the Tsi Ronterihwanónhnha ne Kanien'kéha Language and Cultural Center, interviewed by Marcus Bankuti for The Eastern Door

Be an insider!

Subscribe to our newsletter to get the inside scoop on upcoming exhibitions and cultural events.

Subscribe nowGo green

To come to the Museum downtown, privilege public transit and active transportation!

Tips to go green